In the heart of 1970s Budapest, behind the Iron Curtain and far from the neon splash of 1980s pop culture, a quiet revolution was taking shape. Ernő Rubik, a Hungarian architect and professor of design, wasn’t trying to create the world’s most popular toy. He was trying to solve a problem: how to demonstrate spatial relationships in three dimensions to his students.

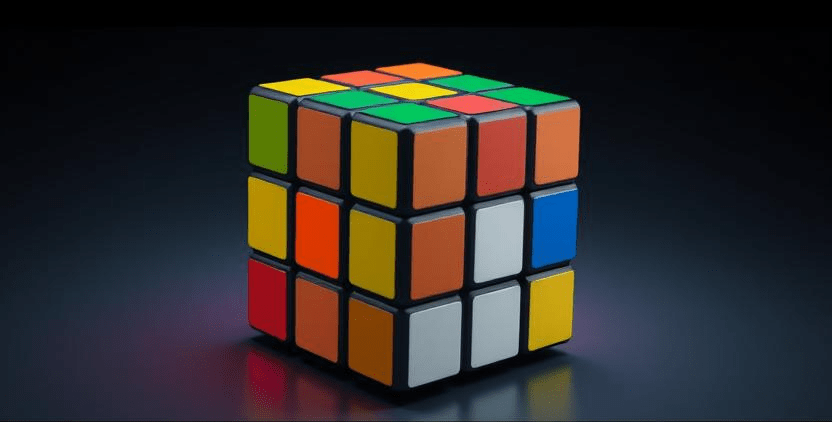

His solution was a wooden model composed of smaller interlocking parts that could rotate independently on three axes. The structure took the form of a 3x3x3 cube, made up of 26 smaller cubelets (with the center cube hidden inside as the pivot mechanism). Each of the six outer faces was painted a different color—red, blue, yellow, green, white, and orange—and the challenge was deceptively simple: scramble it, then restore it so each face returned to a single solid color.

What Rubik had created in 1974 wasn’t a toy, at least not at first. It was a teaching aid, a tool to visually and physically explore 3D movement. He called it the Bűvös Kocka, or “Magic Cube.”

The genius of the invention lay in its mechanical design. The 3x3x3 layout allowed each row and column to rotate independently without the entire cube falling apart—something no one had achieved before. As Rubik turned the cube in his hands, twisting it again and again, he soon discovered a fascinating truth: he couldn’t immediately solve it. The creator himself was stumped. And that’s when he realized he had stumbled onto something extraordinary.

By 1977, the Magic Cube began appearing in Hungarian toy shops, produced by the state-owned company Politechnika. It quickly became a local favorite. But outside Hungary, the world remained unaware—until a chance showing at a toy fair in Nuremberg, Germany, in 1979. There, Tom Kremer, a British toy consultant, saw the cube’s potential. He pitched it to Ideal Toy Corporation, which quickly signed on to distribute it globally.

There was just one problem: the name “Magic Cube” was too generic. It needed something catchier for Western audiences. So Ideal renamed it after its inventor: the Rubik’s Cube.

In 1980, the Rubik’s Cube officially launched worldwide. What followed wasn’t just a successful toy release—it was a pop culture explosion.

The Rubik’s Cube Hits the 1980s

When the Rubik’s Cube hit international shelves in 1980, it didn’t just arrive—it invaded. Backed by Ideal Toy Corporation’s savvy marketing machine, the 3x3x3 puzzle quickly leapt from niche novelty to mass-market obsession. Bright, mysterious, and unlike anything else in toy aisles at the time, it tapped into something perfect for the decade: a hunger for challenges, a fascination with brainpower, and a love for colorful design.

The timing couldn’t have been better. The early 1980s were a golden era for toy innovation and cultural fads. From Atari to Pac-Man, Cabbage Patch Kids to Walkmans, consumers were already primed to latch onto the next big thing. And the Rubik’s Cube was exactly that. Its blocky, rainbow-colored face stood out in toy stores like a disco ball in a library—strange, hypnotic, and irresistible.

Marketing campaigns leaned hard into its “puzzle” nature. Commercials and magazine ads often featured kids and adults alike struggling with and marveling over the cube. Slogans like “Over 3 billion combinations—but only one solution!” played up the mystique, while also inviting everyone to prove they were smart enough to solve it. The phrase “Rubik’s Cube Mania” wasn’t just a tagline—it was a genuine phenomenon.

By 1981, Rubik’s Cubes were flying off the shelves. Over 100 million cubes were sold worldwide in just a few years. In the U.S., toy stores couldn’t keep them in stock. Newsstands sold solving guides alongside comic books. Even cereal boxes and bubble gum brands jumped on the craze, offering miniature cubes as promotional items.

But the cube didn’t just exist in the hands of kids and curious adults—it exploded into every corner of pop culture. Celebrities were photographed with them. Cartoon shows and sitcoms squeezed them into jokes and background props. You couldn’t walk through a mall or a school hallway without seeing someone twisting one in frustration—or triumph.

Perhaps most impressively, it made intelligence cool. The cube didn’t rely on luck, batteries, or brute strength. Solving it took patience, logic, and spatial reasoning. In a decade where surface flash sometimes overshadowed substance, the Rubik’s Cube snuck in both.

For many people, it also became an emblem of the era itself. With its blocky lines, bright colors, and tactile clicking sounds, the cube looked and felt very 1980s—like something designed on a TRON grid, soundtracked by a synthesizer.

By the mid-80s, it had made its way into nearly every household, from suburban basements to urban high-rises. Whether it sat half-solved on a nightstand or fully scrambled on a coffee table, it was there—a cube of chaos waiting to be conquered.

Cube Culture — Tournaments, TV, and T-Shirts

As the Rubik’s Cube swept across the globe, it didn’t just remain a toy—it evolved into a full-blown cultural icon. What started as a personal brain teaser soon became a competitive sport, a fashion statement, and a symbol of intelligence that infiltrated everything from high schools to Hollywood. The 1980s didn’t just play with the cube—they wore it, watched it, and worshiped it.

The competitive spirit around the Rubik’s Cube emerged almost instantly. In 1981, as cube sales soared, the first official Rubik’s Cube World Championship was held in Budapest—home of the cube’s creator, Ernő Rubik. With cameras flashing and nerves on edge, contestants from across the globe gathered to see who could solve the cube the fastest. No pressure, just tens of millions of people watching. The winner, a 16-year-old high school student from Los Angeles named Minh Thai, solved it in 22.95 seconds, and became an instant sensation. This was the birth of what we now call speedcubing.

From there, Rubik’s Cube competitions started popping up in schools, malls, and community centers across the world. Local tournaments gave rise to national contests, often sponsored by toy companies or radio stations. Solvers were separated by time, age, and method—and they came armed with lubricated cubes, custom modifications, and practiced algorithms they could run through with lightning precision. The cube had become a sport, and these were its athletes.

But the cube didn’t stay confined to competitions. It leaked into mainstream media in a big way. It made guest appearances on TV shows like Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood, where Fred Rogers patiently explained how it worked, and That’s Incredible!, which featured cube-solving prodigies as entertainment. Cartoons started slipping in cube gags, often with characters triumphantly solving—or furiously failing to solve—the infamous puzzle. In sitcoms and sketch comedy, it became a shorthand for geekiness, intelligence, or 1980s flavor.

And then came the merchandise. Oh, the merchandise.

By the mid-80s, you could find the Rubik’s Cube logo stamped on everything:

– T-shirts with slogans like “I Solve Under Pressure” or “Cube Addict.”

– Keychains that came with tiny working cubes.

– Stationery sets designed like scrambled cube patterns.

– Even Rubik’s Cube erasers that fell apart in chunks just like the real thing.

There was even a short-lived animated TV show called Rubik, the Amazing Cube (1983), which featured a sentient, flying cube with magical powers who helped a group of kids battle evil. Yes, that really happened. It was weird, it was colorful, and it was exactly the kind of thing the 1980s thrived on.

In classrooms, the cube often walked a fine line between being an educational tool and a distraction. Some teachers embraced it as a way to teach problem-solving and geometry. Others banned it outright after it caused too many students to zone out mid-lecture while twisting silently under their desks.

No matter where you looked in the early to mid-’80s, the cube had left its mark. It had transcended toy status to become a badge of identity. Whether you could solve it or not didn’t matter—it meant something just to own one. To carry it in your backpack. To display it in your bedroom. To twist it anxiously during long phone calls or try to impress a crush with your finger speed.

The Rubik’s Cube had become a cultural phenomenon in the truest sense—everywhere, all at once, and unmistakably of its time.

The Secret Language of the Cube — Algorithms and Solvers

To the uninitiated, the Rubik’s Cube looks like a chaotic mess of colors and corners—a scrambled storm of frustration. But to those who know its secrets, it speaks a quiet, logical language. And mastering that language? That’s where the real fun begins.

At the heart of solving the cube is a methodical approach, not random luck. The Rubik’s Cube operates within a structured system of algorithms—sequences of moves that, when executed correctly, manipulate the pieces without disturbing the progress you’ve already made. Once you understand that, you realize: you’re not guessing. You’re communicating with the cube.

Early on, before YouTube tutorials and apps, solving the 3x3x3 cube was often passed down like folklore. Kids swapped tips on playgrounds, and solving guides were printed in magazines, newspapers, and full-blown books. Some were simple beginner methods; others read like cryptic texts—dense with notation, logic, and diagrams that resembled engineering manuals.

Let’s talk notation. Cube solvers use letters to represent movements:

– R = right face clockwise

– R’ = right face counterclockwise

– L, U, D, F, and B = left, up, down, front, and back

– A prime symbol (‘) means a counter-clockwise turn

– No symbol = a 90-degree clockwise turn

Using this shorthand, a solver might memorize something like:

R U R’ U R U2 R’

This is a common algorithm known as the “sexy move.” (No, seriously—that’s what it’s called in the cube community.) When used at the right time, it helps reposition corner pieces without undoing your earlier work.

Most beginner methods follow a step-by-step approach:

1. Solve the first layer (usually forming a cross on one face)

2. Finish the first two layers

3. Solve the top face

4. Permute the top layer until the cube is solved

Over time, solvers move to more advanced methods like CFOP (Cross, F2L, OLL, PLL), which reduces the number of moves by handling multiple steps at once. It’s the go-to technique for most speedcubers today. Want to solve a cube in under 10 seconds? You’re going to need a whole library of algorithms, lightning-fast finger dexterity, and muscle memory that rivals a concert pianist.

What’s amazing is how the cube offers multiple paths to the same destination. Some solvers prefer intuitive methods, using logic and trial-and-error. Others memorize hundreds of specific algorithms for every scenario. Either way, there’s a deep sense of satisfaction when those final pieces click into place and the colors line up like a digital rainbow.

And then there’s the math. The 3x3x3 Rubik’s Cube has 43,252,003,274,489,856,000 possible combinations—over 43 quintillion. But despite that astronomical number, it’s been mathematically proven that any scrambled cube can be solved in 20 moves or fewer, a number known as God’s Number in cube lore. That fact alone turns the cube from a puzzle into a mathematical marvel.

To cube enthusiasts, solving it isn’t just about completion—it’s about the journey. Every algorithm is a tool. Every twist is a decision. And every solved cube is a reminder that chaos can be tamed, one move at a time.

The Fall and Rise — From 1980s Fad to Timeless Classic

Like so many iconic trends of the 1980s, the Rubik’s Cube eventually hit a wall. By the mid-to-late decade, the fever had broken. Sales declined sharply. Toy aisles made room for newer distractions, from Transformers to Nintendo. The once-ubiquitous cube was suddenly passé, tossed into closets and garage boxes alongside View-Masters and Speak & Spells. The era of Rubik’s Mania was over.

But the cube wasn’t dead—it was just catching its breath.

Part of what contributed to the cube’s initial decline was overexposure. By 1983, there were countless knock-offs, spinoffs, and cube-themed gimmicks flooding the market: Rubik’s Snake, Rubik’s Magic, Rubik’s Clock. Not all of them captured the same magic. The puzzle world had become cluttered, and the original cube’s novelty wore thin. Most people had either solved it once, given up in frustration, or moved on.

Yet the cube remained quietly alive in small pockets of enthusiasts—mathematicians, speedcubers, and collectors. In college dorm rooms and math clubs, it lived on as an underground brain game, respected for its complexity even as it faded from pop culture’s radar.

Then something unexpected happened in the early 2000s: the internet caught on. Suddenly, video tutorials began appearing on YouTube. Forums popped up where cubers could trade algorithms, challenge each other, and track their solve times. The Rubik’s Cube wasn’t just back—it was better, faster, and cooler than ever.

This resurgence wasn’t driven by nostalgia alone. A new generation saw the cube not as a retro toy, but as a tool for sharpening the mind, a competitive outlet, and a social badge. Speedcubing competitions returned in force, now governed by the World Cube Association (WCA), founded in 2004. What was once a quirky toy from the ’80s had become a fully recognized global sport.

And this time, the technology matched the passion. Modern cubes spun more smoothly, could be tensioned and lubricated, and came in magnetic versions for lightning-fast precision. Solvers who once took minutes now broke records in seconds. As of the 2020s, the world record for solving the standard 3x3x3 cube sits well under 4 seconds—light-years beyond the 22.95-second win in 1982.

Meanwhile, the cube’s cultural presence reemerged too. It began popping up again in TV shows, music videos, fashion runways, and even fine art. Designers recreated it as furniture. Luxury brands made versions in gold and crystal. Schools used it in STEM lessons. It was no longer just a relic of the 1980s—it was timeless.

Perhaps the most poetic part of the cube’s comeback is this: it remains unchanged at its core. Despite decades of shifting trends and technological revolutions, the 3x3x3 Rubik’s Cube is still what it always was—a colorful, quiet little challenge. It doesn’t need updates or batteries. Just a curious mind and a pair of hands.

Why the Rubik’s Cube Still Matters

Its legacy in design, education, and pop culture

More than four decades after it first burst onto the scene, the Rubik’s Cube continues to twist its way into our lives—not just as a toy, but as a cultural icon, a brain-training tool, and a symbol of genius. So what makes this little 3x3x3 puzzle endure in a world bursting with digital distractions?

At first glance, the Rubik’s Cube is deceptively simple. Bright, bold colors. A perfect cube. No batteries, no instructions, no screens. And yet within that simplicity is extraordinary complexity. The design itself is a masterstroke—elegant in form, functional in motion, and entirely self-contained. It’s not just a puzzle—it’s an object of beauty. Architects, industrial designers, and artists have often cited the cube as a perfect example of form meeting function. It’s no accident that it’s featured in museums like MoMA in New York. The cube doesn’t just work—it looks and feels good doing it. It’s tactile. It’s symmetrical. And even when it’s scrambled, it’s aesthetically satisfying in a chaotic sort of way.

Educationally, the Rubik’s Cube is a powerhouse. Schools around the world use it to teach everything from spatial reasoning to algorithmic thinking. It’s a gateway to logic, math, problem-solving, and even perseverance. The process of learning to solve it trains the brain to think sequentially, to identify patterns, and to approach problems with patience. What makes it truly universal is its flexibility—it’s as rewarding for a 9-year-old figuring out the first layer as it is for a PhD exploring group theory through the cube’s permutations. And it’s not just about solving—it’s about thinking. Teachers use it to engage students in STEM. Therapists use it to improve fine motor skills and focus. It’s more than a game—it’s a tool for growth.

The Rubik’s Cube is the 1980s—but it’s also beyond the 1980s. It’s shown up in everything from The Simpsons and Family Guy to The Pursuit of Happyness and Stranger Things. Artists and musicians use it to evoke nostalgia, intellect, or just pure retro vibes. It’s wearable. It’s collectible. It’s tattooed on arms, carved into furniture, and splashed across fashion lines. You’ll find it in science museums and music videos alike—one minute being solved by a robot in 0.38 seconds, the next being painted by street artists in giant murals. The cube has crossed boundaries of age, nationality, and generation. You don’t need to speak the same language or grow up in the same era to understand it. You pick it up, you twist it, and suddenly—you’re part of a global legacy.

In a time when attention spans are shrinking and everything has a screen, the Rubik’s Cube remains refreshingly analog. It doesn’t buzz, beep, or scroll. It challenges you to be present. To solve it, you must think, not just tap or swipe. And that alone makes it matter more today than ever before. It’s a symbol. Of intelligence. Of curiosity. Of discipline. And for many, of childhood wonder.

So whether you keep one on your desk, race to beat your best solve time, or just admire its colorful geometry on your shelf, the Rubik’s Cube remains what it always has been:

A quiet revolution in your hands.

Leave a comment