The Arrival of the VHS Player: A Living Room Revolution

There was a moment in time—somewhere between bell-bottoms fading out and shoulder pads coming in—when a silent revolution took place right in the heart of the American household. It wasn’t led by politicians or rockstars, but by a rectangular plastic box that hummed softly and clicked with purpose. This was the dawn of the VHS player—more formally known as the Video Home System—and it transformed home entertainment forever.

Before the VHS player, your television was chained to a broadcast schedule. If your favorite movie aired on a Sunday night, you had to be home at 8 PM sharp, popcorn ready, no exceptions. There was no pausing, rewinding, or rewatching. If you blinked, you missed it. The idea of watching a movie when you wanted was nearly science fiction. But that all changed when the first wave of VHS players started making their way into living rooms in the late 1970s and early 1980s.

The technology behind it all came from Japan. In 1976, JVC (Japan Victor Company) unveiled the VHS format to the world, forever etching its name in tech history. It wasn’t just a sleek innovation—it was a strategic answer to Sony’s rival Betamax format. JVC’s goal was simple but game-changing: create a home video system that was more accessible, easier to use, and capable of recording longer programs. And they nailed it. Their VHS format allowed for up to two hours of video per cassette at launch—perfect for full-length movies or primetime television shows.

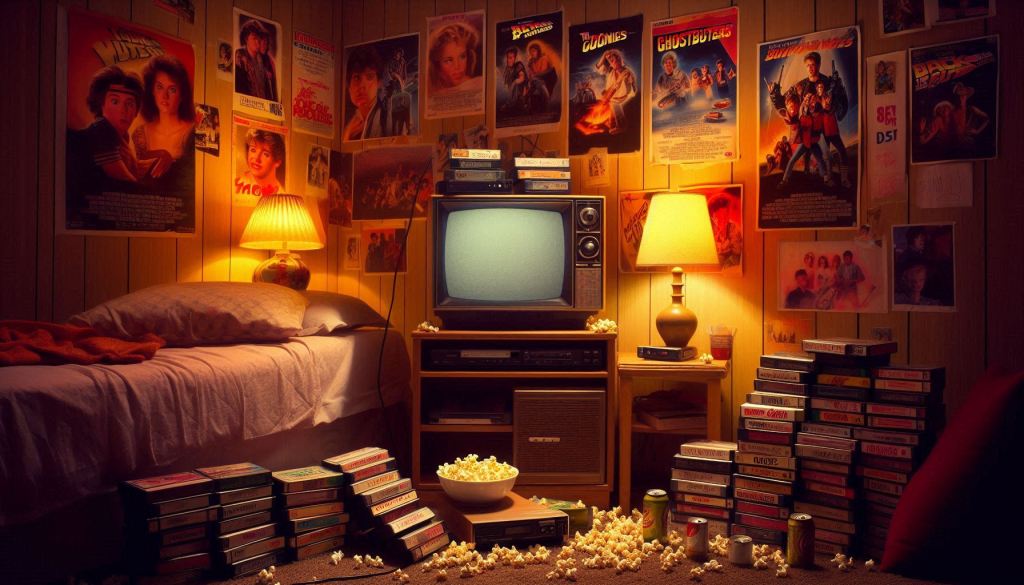

Early adopters were seen as futuristic. These machines weren’t cheap—often costing the equivalent of a month’s salary—but owning one instantly elevated your status. A neighbor with a VCR became the weekend hero. “We’ll bring the snacks if you bring Top Gun,” people would say, and suddenly your living room was ground zero for every movie night in the neighborhood.

What made the VHS player so groundbreaking was its promise: control. Suddenly, the audience had power. You could rent a movie and watch it whenever you wanted. You could own a copy of your favorite film and play it until the tape wore thin. No more waiting for re-runs or edited-for-TV versions that chopped out the good stuff. This little machine gave you the ability to pause your movie when the phone rang, rewind to rewatch your favorite explosion, or fast-forward through the commercials you recorded from live TV.

And then there was the sheer ritual of it all. Loading a VHS tape wasn’t just a push-and-play experience. You slid open the clamshell case, admired the worn label (usually handwritten in black marker), and gently pushed the cassette into the front-loading slot. With a satisfying clunk, the machine accepted your offering, and the whirring began. Some models lit up with glowing red digits, others with green. Many made a gentle mechanical whine as the tape threaded itself around spinning reels inside. It was tactile. It was alive.

In a decade defined by physical media—vinyl records, cassette tapes, Atari cartridges—the VHS player was king. It sat like a centerpiece beneath the bulky box television set, often with a few prized tapes stacked on top or scattered nearby: Ghostbusters, Dirty Dancing, Rambo, The Breakfast Club. And just below the VCR, in many homes, a copy of the TV Guide—because taping your favorite shows required meticulous planning.

But the VHS player wasn’t just about movies. It changed how we watched everything. Birthdays were recorded. Graduations, baby’s first steps, weddings. Camcorders became a fixture at family gatherings, and the VHS player was where those memories lived, replayed over holidays or dusty Sunday afternoons. In a world before digital archiving, this was how we captured life.

And while the device itself looked simple—usually a gray or black box with square buttons and a flickering clock that most people never set—it carried an emotional weight. It was a memory machine. A portal to laughter, thrills, and shared experiences. Families bonded over late-night horror flicks. Kids wore out their favorite Disney tapes. Teenagers hosted sleepovers where The Lost Boys and Heathers ruled the screen.

Owning a VHS player meant freedom. It meant autonomy over what you watched and when you watched it. And in doing so, it changed not just the entertainment industry—it changed us. It brought Hollywood into the living room, and it empowered a generation of viewers to curate their own movie nights, long before algorithms told us what to watch.

When that first VHS player entered your home, it wasn’t just another electronic gadget. It was a ticket to a new world—a world where stories unfolded on your schedule, and magic lived on magnetic tape.

How It Worked: Magic, Mechanics, and the Occasional Tape Muncher

To the untrained eye, a VHS player looked like a simple machine—a black or silver box with a few buttons and a blinking clock that never quite got set correctly. But behind that humble façade lived a miniature world of spinning reels, magnetic tape, and analog wizardry that brought the silver screen straight into our homes. It felt like magic. In reality, it was a symphony of ingenious mechanics—delicate and intricate, often temperamental, but downright revolutionary for its time.

At the heart of the VHS experience was the cassette tape itself. Unlike film reels or laserdiscs, a VHS tape was enclosed in a compact, rugged plastic shell that protected the ribbon-thin strip of magnetic tape wound tightly between two spools. That tape, coated in iron oxide particles, was where the video and audio information lived—recorded and read in analog form. The tape itself was only half an inch wide, but it was capable of holding entire feature-length films, news broadcasts, or precious home videos.

When you inserted a tape into the VCR, a hidden world of motion came alive. The machine “ate” the tape—grabbing it with small rollers and arms, pulling it out of the cassette housing, and wrapping it around a rotating drum known as the video head. This spinning head, angled on a tilted cylinder, read the diagonal tracks on the tape as it moved across at a precise speed. It’s called helical scanning, and it allowed the machine to extract picture and sound in high enough quality to beam a Hollywood blockbuster to your TV set.

Unlike digital devices today, which jump instantly to any moment, VHS was a linear medium. The tape moved in one direction, one moment at a time. Want to rewatch a scene? You had to rewind. Want to skip to the end? Fast forward and watch the blurry streaks rush by. These moments became part of the experience. That distinct whirring and clicking as you waited, the way the screen would flicker to static before the next scene snapped into place—VHS trained us in patience, in anticipation.

Then there was the beloved, sometimes frustrating tracking adjustment. If your picture was shaky or had those annoying horizontal lines at the top or bottom of the screen, you’d fiddle with the tracking dial or press the “Tracking +/–” buttons until the image settled. It was a delicate art. Every tape played a little differently, and older cassettes—especially well-worn rentals—needed a little coaxing to behave.

Of course, not every viewing was smooth. VHS players were infamous for their quirks. The most dreaded of all? The Tape Muncher. It happened when the VCR misaligned the tape, or the internal gears malfunctioned, causing the machine to chew through your cassette like a dog with a new toy. You’d hear that horrible grinding noise, rush to eject the tape, and pull it out only to find the magnetic ribbon mangled and tangled like a tragic spaghetti dinner. If it was a rented movie, you’d panic. If it was your kid’s fifth birthday video, you might cry.

Some brave souls learned to fix tapes themselves. With a tiny screwdriver, some scotch tape, and a lot of hope, they’d open the cassette shell and attempt surgery on the fragile ribbon. It wasn’t always successful, but sometimes that DIY fix could save a precious memory or the only copy of E.T. in your house.

Despite its analog complexity, the VHS system was surprisingly versatile. You could record live TV right onto a blank tape, thanks to the built-in timer record feature—though it often required programming a VCR clock that everyone seemed to forget how to set. Want to skip the commercials? Hit pause during the ad breaks (if you had lightning-fast reflexes). Want to dub one tape to another? All you needed was a second VCR, a couple of AV cables, and a whole lot of patience.

For many people, the first taste of “editing” video came from carefully pausing and unpausing the record button to cut out unwanted segments. It was clunky and imprecise, but it sparked a wave of creativity. Kids would make mock news broadcasts or music video compilations. Parents would create highlight reels of holidays and school plays. VHS made us more than viewers—it made us participants.

And let’s not forget the remote control—if you were lucky enough to have one. Early models were connected to the player with a long wire, which snaked across the floor and inevitably became a trip hazard. Later wireless versions felt space-age, especially with “slow motion” and “frame advance” buttons that turned movie nights into frame-by-frame analysis sessions.

The VHS player wasn’t flawless, but that was part of its charm. Every creak, buzz, and blinking light had a personality. It wasn’t sterile or slick. It was mechanical, real, and a bit unpredictable—like a classic car that needed a few tries to start on cold mornings. But when it worked, it brought movies to life in a way nothing else ever had.

This was more than just a machine—it was a gateway. A portal that brought the Star Wars galaxy into your den, played wedding vows for family members who couldn’t attend, and preserved moments that might have otherwise been forgotten. It was imperfect, yes—but it was tangible, tactile, and unforgettable.

So the next time you see a VHS player gathering dust at a thrift store or tucked away in grandma’s attic, remember: beneath that rectangular shell lies a world of whirring magic and cinematic memories, just waiting to rewind.

The VCR vs. Betamax War: The Battle That Defined a Generation

Before VHS ruled the living room, there was a bitter battle fought between two titans of home video technology. At its core, it was a struggle between VHS, developed by JVC, and Betamax, created by Sony. This wasn’t just about formats. It was about the future of home entertainment, and it shaped how we watched movies for decades.

In the late 1970s, both JVC and Sony introduced their video formats to the market, hoping to dominate the emerging home video revolution. Sony’s Betamax came first, debuting in 1975, with a sleek design and high-quality video resolution. The idea was simple: Sony believed in creating a premium product. Betamax delivered sharper images and better sound, which should have given it the upper hand.

However, JVC’s VHS system had a few advantages that would make all the difference. First, it offered longer recording times. While Betamax could record only 60 minutes of video (ideal for a TV show or short film), the VHS tape could hold 120 minutes—long enough for an entire feature-length movie. This was a significant factor for consumers, who were used to watching full-length films in the theater. A home video system had to match that.

Another pivotal factor was market strategy. Sony, despite the superior quality of Betamax, made the mistake of keeping Betamax closed to other manufacturers. In other words, only Sony could produce Betamax players and tapes. This meant that the supply of Betamax players was limited, and the price was high. On the other hand, JVC took a more open approach, licensing the VHS technology to various companies. This led to a flood of VHS-compatible devices hitting the market. Suddenly, consumers had access to a wide array of affordable VHS players, recorders, and tapes.

The VHS format was democratized—it was everywhere. More manufacturers embraced it, which meant more competition and a drop in prices. VHS became a mass-market product, while Betamax remained niche and costly.

Then, there was the issue of movie rentals. The film industry was the ultimate decider in this battle, and they quickly saw that VHS had the upper hand. Why? Because VHS could record longer content, and more importantly, it had more movie titles available for rent. Betamax simply didn’t have the selection. Rental stores, which would later become icons of the 1980s and 1990s, were key to VHS’s success. A consumer could rent any number of titles—Indiana Jones one week, The Godfather the next—while Betamax just didn’t have that kind of library.

As the 1980s wore on, Betamax began to lose ground, with JVC’s VHS system solidifying its dominance. Sony, once so confident in their superior technology, was forced to pivot. By 1988, Sony finally began to produce VHS players alongside Betamax players, signaling a symbolic surrender to the inevitable. Betamax, despite its technical superiority, couldn’t match the availability of VHS tapes or the sheer number of VHS players in consumers’ homes.

The VHS vs. Betamax war wasn’t just a tech battle—it was a battle of consumer choice. The format war wasn’t won by the “better” product but by the system that could most effectively meet the needs of the market. VHS became synonymous with home entertainment, while Betamax went the way of the dodo.

Looking back, the Betamax vs. VHS battle set the stage for all future format wars—from Blu-ray vs. HD-DVD to the rise of streaming services overtaking physical media. It was a David vs. Goliath story, but in this case, Goliath (VHS) was all about providing what people wanted, even if it meant sacrificing technical perfection for accessibility. The war was a defining moment in the history of media, and it taught a critical lesson in business and technology: it’s not always the best product that wins, but the one that fits the most needs of the consumer.

Recording TV Shows: The Rise of the Home Archivist

Before Netflix queues and digital DVRs, before “on demand” became the norm, there was the sacred ritual of setting your VCR to record a TV show. It was a moment of empowerment—a time when viewers could finally seize control of the broadcast schedule and decide when they wanted to watch their favorite programs. In this era, you weren’t just a passive consumer of television; with a blank VHS tape and a little know-how, you became an archivist, a curator, a time-shifting pioneer.

The concept of recording live television at home was groundbreaking. For decades, television had operated on a fixed, linear schedule. If you missed an episode of MASH* or Cheers, you were out of luck. There were no replays, no “catch up” options. You simply had to wait for a summer rerun and hope it aired again. But with the arrival of the VHS player and its built-in timer-recording function, that all changed. Now, you could record a show while you were at work, out to dinner, or—most thrillingly—record one channel while watching another.

Of course, programming your VCR was no small feat. Early models had bulky remotes and manual dials. Later versions introduced digital displays, where you’d enter the channel, start time, end time, and tape speed. This required precision and patience—and more than a few curses when you discovered you’d accidentally recorded three hours of static because the VCR was set to channel 3 instead of 5.

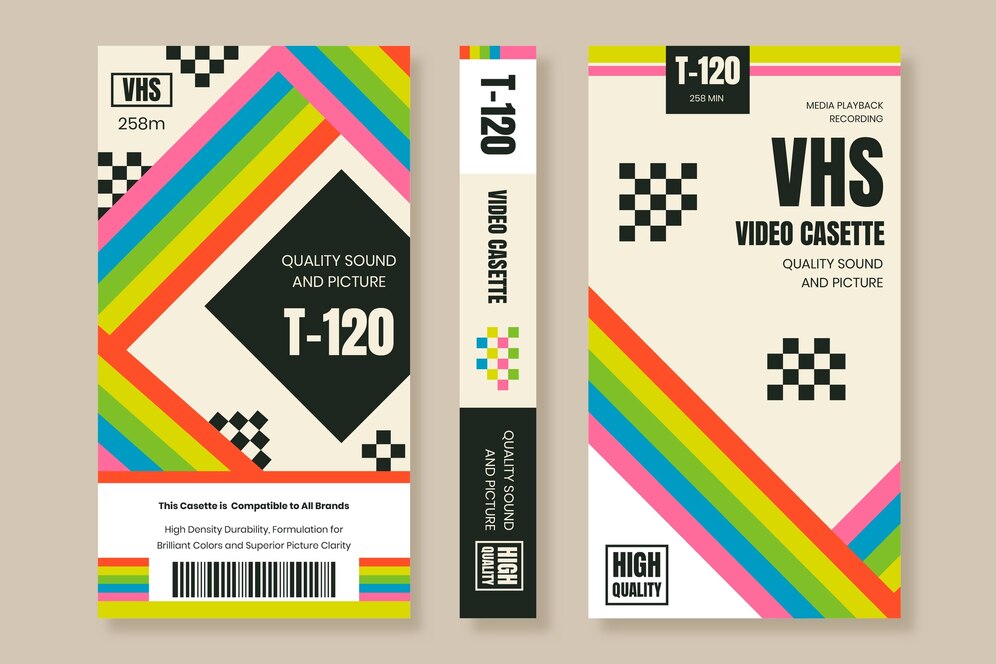

Even more challenging? Recording multiple episodes across days. Ambitious viewers would crack open the Sunday newspaper’s TV listings, highlighter in hand, and create a weekly battle plan. The strategy often revolved around maximizing tape space. A standard T-120 tape could hold up to two hours on SP (Standard Play), four hours on LP (Long Play), or six hours on EP (Extended Play), with decreasing video quality the longer you stretched it. But for TV shows, especially sitcoms and cartoons, most people didn’t mind a little fuzz or tracking issues. The goal was volume—to preserve as much as possible.

Kids in the ‘80s and ‘90s practically grew up with stacks of VHS tapes labeled in black marker: “X-Men Episodes 1–4,” “TGIF – Full House/Step by Step,” “Simpsons Halloween Specials,” “Buffy Season 2 (Don’t Tape Over!!).” These tapes lived in drawers, cardboard boxes, or milk crates. They were passed around between friends. And for many fans, they became the only record of shows that were otherwise unavailable commercially.

This DIY archival culture extended beyond scripted TV. People recorded everything—MTV music video blocks, Saturday morning cartoons, news reports, award shows, even full sports seasons. Some became obsessed with preserving entire marathons: every Halloween special on Nickelodeon, or the full New Year’s Eve countdown from Times Square. Commercials, which we now edit out or skip, became cherished artifacts of their own. Watching an old tape in the 2000s and stumbling across a Blockbuster Video ad or a Pizza Hut jingle from 1994 could feel like opening a time capsule.

For families, the VCR also doubled as a memory machine. While camcorders were their own branch of the VHS family tree, they worked hand in hand with the VCR. You could record a birthday party, dance recital, or holiday morning on camcorder tape, then dub it onto a standard VHS to share with grandparents—or immortalize it with a scrawled label: “Christmas ’88 – Don’t Erase.”

Some parents became home editors, pausing during commercials or trimming scenes to remove content they didn’t want their kids to see. You’d get a version of The Goonies where all the swearing had mysteriously vanished, or a horror movie with the most graphic scenes removed. These curated tapes became unique cultural artifacts, shaped by taste, timing, and the occasional finger slip on the pause button.

There was also a small but dedicated subculture of VHS collectors who took this a step further—tape traders. These fans would mail copies of rare or foreign broadcasts to one another, sharing hard-to-find content like anime not aired in the U.S., obscure horror films, or live concerts. It was a thriving underground economy based entirely on magnetic tape, envelopes, and mutual trust.

The ability to record TV gave viewers a sense of control over something that once felt monolithic and untouchable. For the first time, the television industry wasn’t dictating what you watched or when—you were. It was an era of homemade box sets and marathon weekends before “binge-watching” had a name. People got creative. Kids made fake commercials between shows. Fans edited together their favorite moments from Friends, complete with custom title cards. The VCR turned passive watchers into storytellers and historians.

Of course, mistakes were part of the ride. Everyone has a story of accidentally recording over a favorite tape. Maybe it was your wedding video overwritten by a Seinfeld rerun. Or that once-in-a-lifetime Super Bowl halftime show lost forever under an old sitcom. You’d hear the sound drop, the image warp—and your heart would sink. But that was the deal with VHS: it was fragile, it was flawed… and it was real.

In hindsight, recording TV shows on VHS was one of the most democratizing acts in entertainment history. It handed power to the viewer and turned living rooms into miniature libraries. It paved the way for everything we take for granted today—streaming queues, cloud DVRs, YouTube channels. It showed us that stories could be preserved, shared, and loved on our terms.

So next time you’re scrolling past endless thumbnails on a streaming platform, remember: before algorithms and autoplay, there were tapes labeled in Sharpie, rewound with a pencil, and queued up for Friday night—lovingly recorded by someone who just didn’t want to miss a moment.

Tracking Troubles and Tape Heads: The Struggles Were Real

For all its nostalgic charm, the VHS experience wasn’t exactly seamless. Owning a VCR meant learning to live with—and occasionally battle—its many quirks. Unlike today’s frictionless digital media, VHS was mechanical, imperfect, and wonderfully analog. And if you grew up with it, you probably became a part-time technician without even realizing it.

Let’s start with the most infamous villain of the VHS era: tracking.

If you’ve ever watched a VHS tape and seen the screen flicker with wavy lines, jittering images, or a bar of static crawling up or down the screen, you’ve witnessed a tracking issue. Tracking referred to the alignment between the tape’s recorded signal and the VCR’s read head. When things didn’t line up quite right, the picture would suffer. Sometimes it was minor—just a bit of fuzz along the bottom. Other times, it made the movie practically unwatchable.

VCRs typically had a tracking adjustment, either manual (a dial or button) or automatic in later models. Adjusting it became part of the routine, especially when switching between different tapes. Each VHS cassette had its own quirks—some played clean, others were like trying to watch a movie through a snowstorm. The process required patience and finesse, and sometimes a little luck. And it was a delicate dance. Fix the top of the picture, and suddenly the bottom would go haywire. You’d sit there tapping the tracking button over and over, praying for a sweet spot.

Then there were the tape heads themselves—the core components inside the VCR responsible for reading the video and audio data from the tape. Over time, those heads would get dirty, gummed up with magnetic dust and microscopic debris. The result? Fuzzy images, loss of sound, and that dreaded screen of static snow. To combat this, you had two options: buy a cleaning tape (a VHS cassette loaded with a special cleaning fabric and fluid) or go in manually with rubbing alcohol and cotton swabs, which felt a bit like performing surgery on your VCR.

Cleaning was one thing. Repairs were another. Sometimes tapes would get stuck. Worse, they’d get chewed. You’d hear a horrible grinding noise and open the VCR to find your precious tape crumpled, twisted, or torn. The player’s rollers could misfeed the tape or jam it during playback, often mangling scenes beyond recognition. A pencil or pinky finger could sometimes rewind it gently back into the cassette housing, but other times, the damage was permanent. That meant heartbreak—especially if it was a cherished recording or a rental you’d have to pay to replace.

Speaking of rentals, you could always tell which tapes had been around the block. They had loose cases, rattling spools, and the occasional mystery rattle when shaken. The labels were often faded, the corners curling. And almost all of them suffered from what some called “rental fatigue”—soft, grainy playback caused by overuse. That’s the thing with magnetic tape: it degrades. The more you watched, rewound, and rewatched a tape, the worse it got. Favorites paid the price. That one cartoon you watched a hundred times? By year two, it looked like it had been filmed through a shower curtain.

And don’t forget the built-in war between the VCR and the TV. These machines didn’t always speak the same language. You had to switch to the right input—channel 3 or 4—or use a coaxial cable switchbox. Some VCRs used RCA composite cables, but not all TVs had the inputs, especially older ones. If the audio was too low, you had to crank the volume. If it was too high, it came out tinny and distorted. Getting everything to sync up felt like solving a puzzle every time you pressed play.

Rewinding was its own little struggle. Some VCRs had sluggish rewind speeds that made you wait an agonizing five minutes to get back to the beginning. And heaven help you if you forgot to rewind a rental—cue the passive-aggressive sticker: “Please Rewind Before Returning.” Some people solved this by buying a separate rewinder—an odd little gadget shaped like a miniature car or brick that only existed to rewind tapes faster, saving wear on the VCR.

Weather also played a part in VHS viewing. Humidity could warp tapes. Cold rooms made the plastic brittle. Static from dry air could mess with playback. And let’s not even get into what happened when someone put a tape near a magnet or speaker. That was the kiss of death.

Despite the hassles, most people didn’t complain too much. VHS was still magical. Watching a movie at home was a privilege. The imperfections became part of the charm. The grainy image, the occasional flicker, the way a tape would stretch the audio ever so slightly near the end—those quirks became familiar, comforting even. And for many, tinkering with the machine was a small price to pay for having full control over your entertainment.

Owning a VCR was a rite of passage. It taught you patience. It taught you resourcefulness. It taught you that good things sometimes came with a few hiccups—and that with a little tracking adjustment, you could still enjoy the show.

Fast-Forward, Rewind, Repeat: Living with Limitations (and Loving It)

In the age of streaming and instant gratification, it’s easy to forget just how limited VHS technology really was—and how little that mattered. The experience of watching a movie or show on VHS was slower, more deliberate, and a little clunky. But those very limitations created a kind of ritual. There was a rhythm to VHS, a tactile interaction with media that made the experience feel personal and oddly satisfying.

Let’s start with the basics: you couldn’t skip scenes with a click. If you wanted to jump ahead to your favorite part in a movie, you had to fast-forward through everything that came before it. That meant holding down the button and watching the screen as the image blurred into smeared streaks of color. You’d try to catch just the right moment to hit play, usually overshooting it, then rewinding a few seconds, then trying again. This dance could go on for minutes, especially if you were searching for that one perfect line, that one killer action scene, or the part that always made you laugh.

Want to rewatch it? Back to the rewind button. Want to skip the opening credits? Get ready to watch them at 4x speed. Want to avoid the commercials you forgot to cut out of your home-recorded shows? Fast-forward and pray you don’t miss the beginning of the episode.

And then there was rewinding at the end. It wasn’t optional—it was expected. Rental stores even penalized you for skipping it. That small “Please Be Kind, Rewind” sticker wasn’t just friendly advice. It was a social contract. If you didn’t rewind, the next person had to. And if you returned too many tapes unrewound, you might end up with a fine—or at least some serious side-eye from the video store clerk.

But these limitations gave VHS a kind of structure. You didn’t skip around or binge-watch in the modern sense. Watching a movie on tape was an event. It required commitment. You sat through the entire thing, from fuzzy previews to the final credits. It felt more like going to the theater than scrolling through a library of endless thumbnails.

Even the quality of the image reminded you that you were watching a physical format. Every tape had a slightly different visual signature. Some were crisp; others were grainy or slightly warped at the edges. You’d see faint ghosting, wavy lines, the occasional color bleed. The audio sometimes wobbled. If you paused the tape, the screen would freeze with a horizontal shimmer, and on older VCRs, the image would roll or distort.

There was no perfection with VHS—but that’s what made it so memorable. You weren’t watching something sterile or standardized. You were watching a copy—a unique, physical object with its own quirks, its own signs of wear. You knew which tapes had been watched a hundred times by how long they took to start, or by the slight jitter when the studio logo appeared. Your copy of Jurassic Park might not look exactly like your neighbor’s, and that made it yours.

And when it came to home recordings, the experience got even more personal. Many tapes had little handwritten labels, sometimes scribbled in haste: “Saturday Cartoons,” “Movie Night – Summer ‘94,” “Mom’s Soap Operas.” Sometimes you’d tape over something older and catch a few seconds of it at the beginning—five seconds of a local news broadcast before Star Wars kicked in. Or a ghostly fade-in from a birthday party video recorded months earlier. These accidental layers gave tapes a kind of living history, a glimpse into your own media past.

The limitations of VHS also encouraged creativity. If you had a dual-deck VCR, you could make your own compilations. Favorite scenes from movies. Music videos from MTV. Home videos edited into highlight reels. It wasn’t easy, and the results weren’t perfect—but the process was part of the fun.

You could even find clever workarounds. Didn’t want to watch the previews at the start of a rental tape? Fast-forward and hope you guessed where the movie actually started. Want to skip a part you didn’t like? Fast-forward, then rewind if you missed too much. Want to replay a scene over and over again? Good luck finding it the same way twice.

And let’s not forget the thrill of watching a worn-out tape—the kind that had been played so many times the colors had faded, the sound warped slightly, the image occasionally jittering with every spin of the spool. Those were the true favorites. The ones you knew by heart. You didn’t need pristine quality. You just needed the story.

In a strange way, the limitations of VHS made you more present. You paid attention. You couldn’t scroll on your phone or multitask. You had to sit there, watching, listening, waiting. The process slowed you down, and in doing so, it made the moment feel more intentional. More real.

So yes, VHS was slow. Yes, it was clunky. Yes, it came with rewinding and tracking and waiting. But it was also warm. Familiar. Full of character. The imperfections were part of the experience. And for a whole generation, those limitations didn’t feel like obstacles. They felt like home.

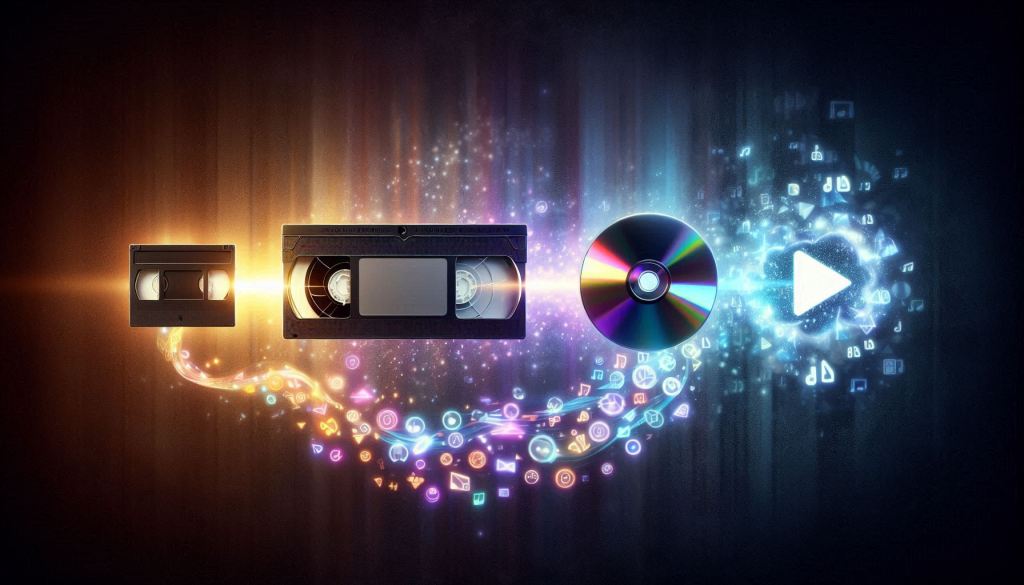

Fade to Black: How DVD and Streaming Replaced a Beloved Giant

All good things come to an end. And for VHS, the end came gradually, then all at once. After years of reigning supreme in living rooms across the world—after building empires like Blockbuster and reshaping the way we consumed stories—VHS began to fade into obsolescence. It didn’t go quietly, but it couldn’t withstand the pace of progress forever. By the early 2000s, the once-essential tape had become a relic of a different era, replaced by the sleek promise of the future: DVD, and later, streaming.

It started with subtle shifts. The DVD arrived in the late 1990s like a spaceship landing in a parking lot full of station wagons. Discs were shiny, light, and—most importantly—digital. They offered crisp picture quality, surround sound, no rewinding, and a menu system that felt like magic compared to the linear nature of VHS. With just a click, you could jump to your favorite scene, turn on subtitles, or explore behind-the-scenes footage. Special features became a selling point. No more blurry tracking lines. No more chewed tapes. No more fast-forwarding for fifteen minutes to find that one joke you liked in the middle of Ghostbusters.

The shift to DVD was rapid. Studios began releasing movies on both formats during the early transition, but it didn’t take long before DVD-only releases became the norm. Rental stores started dedicating more shelf space to discs. Customers who once came in for the familiar clunk of a plastic tape case were now drawn to the glossy, space-saving appeal of DVDs. And the price of DVD players dropped quickly, making the leap even easier.

But there was more to the death of VHS than just new technology. The entire culture around media consumption was shifting. People didn’t just want to watch movies—they wanted convenience. The DVD offered that. Then came the DVR, digital cable, and finally, the internet. Once you could download or stream a movie without leaving your couch—or even wait for a disc to arrive in the mail, thanks to Netflix’s original DVD-by-mail model—the writing was on the wall.

Blockbuster tried to adapt. The company introduced DVD rentals. It experimented with online services. But its foundation was built on a model that couldn’t pivot fast enough. By the time streaming became viable, Blockbuster was a sinking ship, its aisles of VHS tapes and even DVDs gathering dust while the world moved on. The giant that once stood at the center of Friday night plans was eclipsed by the very technology it helped normalize: entertainment at home, on your terms.

By the mid-2000s, VHS was effectively dead in the retail world. Major studios stopped releasing new titles on tape. Manufacturers stopped producing VCRs. Stores cleared out their stock. The last major motion picture released on VHS in the U.S. was A History of Violence in 2006—an ironic title, considering what had just happened to the format.

Still, VHS didn’t disappear completely. For collectors, nostalgia-seekers, and analog purists, tapes never lost their charm. Independent video stores—where they still existed—held on to their stock as long as they could. Horror fans, in particular, kept the flame alive, drawn to the gritty, low-fi feel of VHS that perfectly matched the spirit of cult classics and low-budget slashers.

And something strange happened in the years after VHS “died”—it was reborn as a retro treasure. People began rediscovering old tapes at garage sales and thrift stores. Some even started collecting them like vinyl records, curating shelves filled with sun-faded clamshell Disney releases and long-forgotten TV specials. VHS became a statement—a rebellion against the sterile perfection of digital. It became cool to pop in a tape, hear the whir of the spools, and watch a movie the way people did decades earlier.

There’s something about VHS that modern formats can’t quite replicate. The physicality. The ritual. The sense of occasion. You didn’t just stream a movie—you went to get it. You held it in your hand. You slid it into a machine. You watched it, warts and all, and when it was over, you rewound it for the next time. There was effort involved. And maybe that made it feel more valuable.

So yes, VHS is gone. But its legacy is everywhere. The idea of choosing your own movie, of watching it when you wanted, of making a night out of it—that didn’t die with the tape. It just evolved. Every time you fire up a streaming service and scroll through options, you’re echoing the same experience we once had wandering the aisles of a video store. Only now, the aisles are infinite, and the tapes never wear out.

The rise and fall of VHS wasn’t just the story of a format—it was the story of how we learned to love movies on our own terms. Of how we brought the magic of the theater into our homes. Of how we rewound, fast-forwarded, paused, and played our way through childhoods, Friday nights, snow days, and sick days.

And even now, long after the last VCR has been unplugged, somewhere out there in a basement or attic, a tape labeled “Summer Movies ‘89” still sits quietly on a shelf—waiting for someone to press play one more time.

Leave a comment