In a world before smartphones, Bluetooth, and AI assistants, there was a time when technology felt like magic—clunky, whirring, glowing magic. The 1980s were a golden age of gadgetry, where innovation surged ahead and anything that beeped or blinked was a glimpse into the future. Back then, owning a gadget wasn’t just convenient—it was a status symbol, a conversation starter, and sometimes even a rite of passage.

But as quickly as they arrived, many of these once-revolutionary devices became relics, collecting dust in basements and thrift store bins. What was once cutting-edge is now obsolete, but that doesn’t make these gadgets any less fascinating. In fact, revisiting them gives us a unique window into the optimism, ingenuity, and sheer audacity of ’80s tech culture.

In this post, we’ll take a look at ten forgotten heroes of the high-tech revolution—gadgets that were once marvels, and now serve as digital fossils of an analog world.

1. The Walkman: The Birth of Personal Soundtracks

Before digital playlists and wireless earbuds became the norm, the ultimate symbol of portable music in the 1980s was the Sony Walkman. Introduced just before the new decade began, it quickly became a cultural and technological phenomenon. Owning a Walkman wasn’t just about listening to music—it was a statement. For the first time, people could take their favorite songs with them, walking through the streets, riding the bus, or jogging through the park, all while enveloped in their own private audio world. Music, once a shared experience played through radios or home stereos, suddenly became deeply personal.

The design of the original Walkman reflected the era’s fascination with sleek, modern aesthetics. Often encased in aluminum or brightly colored plastic, with large mechanical buttons and that signature clear cassette window, it was as much a fashion accessory as it was a piece of tech. And those orange foam headphones? Instantly recognizable. Spotting someone wearing them meant they were living life to their own soundtrack, even if that soundtrack was the same Top 40 hits blaring in every other Walkman in town.

One of the most profound side effects of the Walkman’s popularity was the rise of the mixtape. Suddenly, creating a custom cassette filled with favorite songs—or messages disguised as playlists—became a powerful form of communication. These carefully curated tapes became the 1980s version of a social media post: part confession, part expression, and part connection. Whether it was a crush, a friend, or just a personal mood booster, the mixtape era thrived because the Walkman made it meaningful.

As the device gained popularity, countless other companies jumped on the trend, producing knockoffs and cheaper alternatives. But the name “Walkman” stuck, often used generically to describe any portable cassette player. It was the kind of brand success that marketing teams dream about. Still, Sony remained at the top of the heap, continuously updating the design with slimmer models, auto-reverse features, and eventually versions that played radio or offered improved sound fidelity.

By the late 1990s, the magic began to fade. Compact discs, digital players, and eventually smartphones rendered the cassette obsolete. Rewinding tapes became a nuisance, and the analog hiss and occasional tape snarls couldn’t compete with crystal-clear digital files. Yet for those who lived through its reign, the Walkman remains a vivid symbol of freedom, individuality, and a very specific kind of joy. It wasn’t just about the music—it was about the experience of hearing that music anywhere you chose.

The Walkman didn’t just change how people listened. It changed how they moved through the world—with purpose, rhythm, and a sense of personal soundtrack long before playlists were a tap away.

2. The VHS Camcorder: Capturing Life One Grainy Frame at a Time

In an era when photography still ruled as the primary means of documenting personal history, the arrival of the VHS camcorder in the 1980s marked a radical shift in how people preserved their lives. Suddenly, memories could move, speak, laugh, cry, and stumble awkwardly through school plays. The VHS camcorder was a high-tech marvel that brought the dream of filmmaking into the living room, democratizing video production in a way the world had never seen. Despite their size and quirks, these devices quickly became prized possessions—symbols of modernity, middle-class achievement, and a newfound intimacy with technology.

Unlike the compact digital devices of today, the VHS camcorder was a beast. The earliest models were large and heavy, often resting on the user’s shoulder like a television news camera. With full-sized VHS cassettes slotted directly into the device, it was as much a workout tool as it was a recording instrument. Carrying it around at family gatherings or during vacations felt like hauling around a piece of professional gear, and in a sense, it was. With just the press of a red button, the average person could now create something that looked and felt like real media. It was power in the hands of the ordinary, and people embraced it with enthusiasm.

Though the image quality was grainy and the audio often muffled by the hum of internal mechanisms, there was nothing else like it. You could watch the footage moments after filming it by popping the tape directly into your VCR—no development process, no darkrooms, no waiting. That immediacy was mind-blowing in a decade still used to analog delays. Suddenly, Christmas mornings, birthday parties, and beach trips weren’t just fleeting experiences. They could be replayed, again and again, in all their awkward, candid glory.

This led to a new phenomenon: the performative home moment. Once the camcorder entered a room, the behavior of everyone in its field of vision shifted. Parents urged their children to smile wider, relatives adjusted their posture, and even pets seemed to behave differently under the pressure of the blinking red record light. Life became a little more staged, a little more self-aware, as everyone realized that what was being recorded might be watched years later—or worse, shown to guests. The phrase “act natural” became a household joke, because nothing about being recorded on a VHS camcorder felt natural.

The camcorder also gave rise to the infamous home video blooper. Missed lines, awkward silences, forgotten birthdays, and disastrous dance routines were immortalized in clunky footage that, years later, would become sources of both embarrassment and joy. America’s Funniest Home Videos, which debuted at the end of the decade, drew heavily on these amateur recordings, proving just how widespread the technology—and its often hilarious results—had become.

Beyond the living room, VHS camcorders had an unexpected cultural impact. Local communities began producing public access television shows using these devices. Aspiring filmmakers shot their first projects with them, inspired by the dream of making it big. School projects took on a whole new dimension, with homemade documentaries and video essays suddenly within reach. The camcorder became more than a recording device; it was an entry point into storytelling, creativity, and even a kind of journalism.

Of course, there were technical frustrations. Batteries were large and drained quickly. Autofocus was unreliable, and manual focus required an incredibly steady hand. The built-in microphones were notorious for recording the sound of the user’s own breathing or rustling shirt. And the tapes—though magical—could be accidentally recorded over or degraded with repeated playback. But for most users, the trade-offs were worth it. The imperfections became part of the charm. The shakiness, the muffled dialogue, the camera abruptly pointed at the ground—all of it made the footage feel authentic and human.

By the mid-1990s, smaller formats like VHS-C and Hi8 began replacing full-size VHS camcorders, and eventually digital camcorders rendered the tape format obsolete altogether. But during its reign, the VHS camcorder wasn’t just a gadget—it was a memory machine. It changed how people saw their lives, how they told their stories, and how they remembered their past. Even today, when those old tapes resurface—filled with ghostly echoes of childhoods, family pets, and outdated furniture—they remind us of a time when filming something was intentional, meaningful, and often filled with love.

The VHS camcorder didn’t just record the 1980s—it helped define how we remember it.

3. The Pager (Beepers): When a Buzz Meant Urgency and Status

Long before text messages, push notifications, or DMs, there was a tiny device clipped to belts and tucked into pockets that carried a certain air of urgency, mystery, and cool: the pager. Often referred to simply as a “beeper,” this compact gadget was a staple of 1980s technology—a communication tool that thrived in an era before everyone was perpetually connected. For a generation, hearing that distinct beep or buzz meant someone needed you now, and in that moment, you were important.

At its core, the pager was a simple device. It received numeric messages—typically phone numbers—that the user would then call back from a landline or payphone. That’s it. But in the context of the 1980s, that level of mobility was unprecedented. Until then, if you weren’t near a phone, you were unreachable. The pager offered a lifeline of communication that extended beyond the reach of a telephone cord. It was a way to be on the move without falling off the grid completely, and for that reason alone, it felt like a glimpse of the future.

Initially, pagers were used almost exclusively by medical professionals, emergency workers, and high-level executives—people whose presence could mean the difference between life and death, or millions gained and lost. When someone saw a pager on your hip, it signaled authority, responsibility, and a job that didn’t operate on a 9-to-5 schedule. It was a silent badge of importance, especially in industries where timing was everything. But as the technology became more affordable and the networks expanded, pagers slowly found their way into the mainstream.

By the mid to late 1980s, they had become a cultural phenomenon. Teenagers coveted them as status symbols, despite having no urgent reason to be reached. Drug dealers, famously, adopted them as tools of their underground trade, giving the devices an edge of street credibility in some circles. At the same time, suburban dads clipped them to their belts with pride, treating each beep as if it came from a Fortune 500 company rather than the family’s dentist office. The ambiguity of who might be paging you gave rise to a unique kind of power. You didn’t know who was trying to reach someone—but clearly, someone needed them, and that made all the difference.

Pagers also introduced a new kind of language: numeric code. Because the early devices could only receive digits, users started developing shorthand messages. “143” meant “I love you,” “911” indicated an emergency, and certain number combinations mimicked words when viewed upside down on a calculator-style screen. These codes became a secret language among friends and couples, creating an early, analog version of texting that required both creativity and memorization.

Of course, there were drawbacks. You couldn’t respond directly to a page, so the device essentially served as a digital summons—you’d then have to locate a phone, hope for a dial tone, and call back. If you ignored a page, it was seen as a deliberate snub. And if you answered too quickly, it suggested you had nothing better to do. Managing your pager etiquette became a subtle social skill, a strange precursor to the modern anxieties around read receipts and “why didn’t you reply?”

As cell phones started to rise in the 1990s, the pager’s role began to shrink. Devices that could both send and receive calls and messages made the pager feel limited, even quaint. But for a significant period in the 1980s, the pager was cutting-edge. It reshaped expectations about availability, accessibility, and communication. It also quietly redefined what it meant to be important in a fast-moving world. Being paged suggested that your time was in demand, that your attention mattered—and that was an intoxicating idea in a society increasingly obsessed with productivity and status.

Today, pagers are mostly forgotten, or used only in extremely niche scenarios where their reliability outshines cellular networks. But their legacy lives on in every text notification, every buzz on a smartwatch, and every moment when a screen lights up with someone trying to reach you. The pager may have been simple, but it was profound in what it represented: the first true signal that the world was shifting toward constant, portable connection. In that sense, the beeper wasn’t just a gadget—it was a preview of the 21st century.

4. The Cordless Landline Phone: Cutting the Cord Before It Was Cool

In the pantheon of 1980s tech, few devices captured the thrill of newfound freedom quite like the cordless landline phone. At first glance, it might seem tame compared to today’s mobile marvels, but back then, it was a revelation. Suddenly, you could talk on the phone and walk around the house at the same time—a novelty that felt like science fiction in a world still dominated by spiral cords, wall jacks, and kitchen phones mounted under cabinets.

The typical phone call in the early part of the decade was a stationary affair. You picked up a handset connected to a base by a coiled cord that either tangled like seaweed or was stretched to unnatural lengths by teenagers seeking privacy down the hallway. The phone’s location dictated the conversation—living room chats lacked discretion, kitchen calls invited interruptions, and bedroom phones, if you were lucky enough to have one, were a prized teenage luxury. The introduction of the cordless phone shattered that immobility. For the first time, users could talk from the backyard, the basement, or even while pacing laps around the kitchen island, free from the physical leash of copper wire.

Early models of cordless phones were bulky, often shaped like oversized bricks with retractable antennas that extended like radio towers. The bases were just as clunky, featuring long telescoping antennas meant to transmit signals across what, at the time, felt like vast distances—usually 50 to 100 feet. Interference was a given. Microwave ovens, baby monitors, or even the neighbor’s phone could disrupt a conversation, injecting static or, occasionally, letting you eavesdrop on someone else’s chat entirely. Still, the minor chaos added to the excitement. Talking wirelessly at home gave the illusion of luxury and technological edge, even if you had to shout over a burst of radio noise every few minutes.

Owning a cordless phone in the ‘80s wasn’t just about convenience—it was about status. It said something about your household: that it embraced innovation, that it wasn’t afraid of newfangled electronics, and that it had an eye on the future. The devices weren’t cheap, and their battery life was laughable by modern standards. Leaving the handset off the base for too long meant it would go dead, often mid-call, forcing you to scramble for a corded backup before the line cut out. Yet even with these limitations, cordless phones became wildly popular, spreading rapidly through suburban homes and becoming the centerpiece of kitchen counters everywhere.

The design evolved quickly. The earliest units often had twelve chunky physical buttons and LED indicators, but later models introduced sleeker profiles, backlit keypads, and more reliable signal encryption. Still, the fundamental magic of the cordless phone remained unchanged: mobility within the home. For teens, it meant taking private calls into the garage. For busy parents, it allowed multitasking—folding laundry, stirring dinner, or chasing toddlers while chatting with relatives. For everyone, it meant freedom in an age when mobility was still mostly associated with cars, not communication.

Perhaps what made the cordless phone so impactful was how it subtly changed behavior. Phone calls became longer, more casual, and more spontaneous. You could chat while watching TV or pace the floor during difficult conversations. The psychological shift from being tethered to standing untethered, even in your own home, laid the groundwork for how we would later interact with mobile phones. It normalized the idea that communication didn’t have to be rooted to one spot. You didn’t have to “go to the phone” anymore—it could come with you.

Of course, cordless phones had their quirks. Static was common, dropped calls happened if you strayed too far, and security was laughable by today’s standards. Some models transmitted analog signals that could be picked up by hobbyists with radio scanners, turning personal conversations into potential public broadcasts. But for most users, those flaws were worth the tradeoff for the sheer thrill of walking while talking, something that previous generations never imagined would be possible without a rotary dial and a 20-foot cord stretched into the next room.

As cellular phones rose to prominence in the 1990s, the cordless landline phone quietly took a backseat. But it left a legacy. It was the transitional device that bridged the gap between static, fixed communication and the fully mobile era we live in today. It trained people to expect movement, to feel unshackled from wires, and to redefine what a phone conversation could look like.

The cordless phone may seem quaint now, but in the context of the 1980s, it was a revelation—a freedom-giver, a domestic transformer, and a silent foreshadowing of the mobile revolution to come.

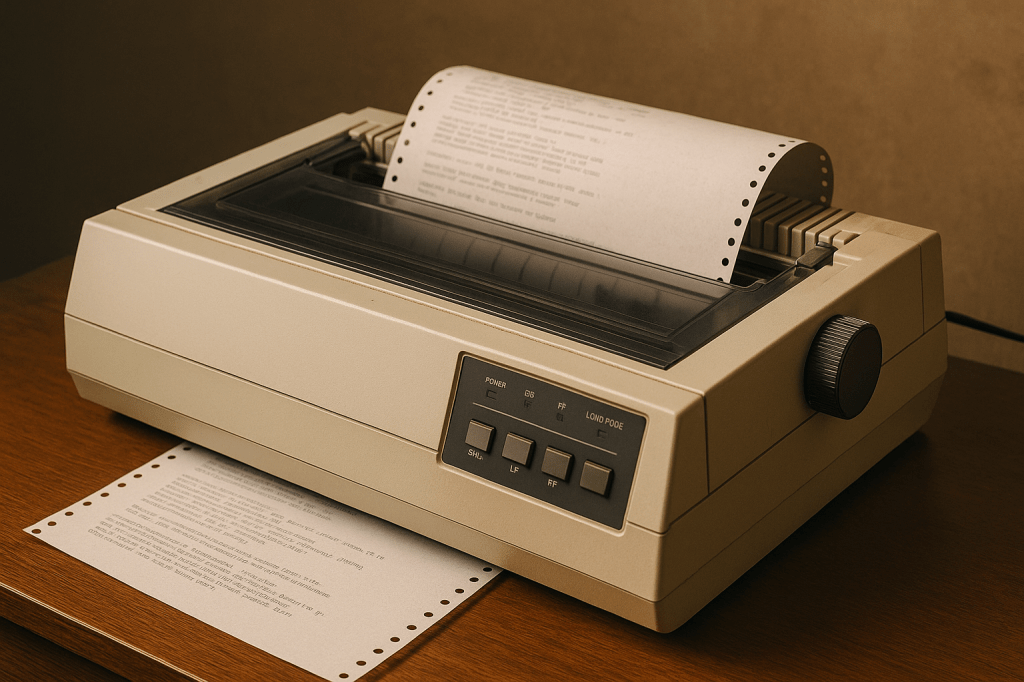

5. The Dot Matrix Printer: Loud, slow, and magical in its time.

Long before laser printers hummed quietly in sleek home offices or inkjets spat out vibrant color photographs in seconds, there was the dot matrix printer—a loud, clunky, and unmistakably mechanical beast that was somehow both marvel and menace. In the 1980s, this was cutting-edge tech, a workhorse peripheral that brought the power of printed words into homes and offices in a way that felt nothing short of revolutionary. If you’ve never heard the grinding wail of a dot matrix printer firing up, you’ve missed one of the defining soundtracks of the early digital age.

Dot matrix printers didn’t just print—they performed. The printing process was an audible event, a theatrical mix of whirrs, squeals, and rhythmic clatters that often sounded like a robot typewriter suffering an anxiety attack. They worked by rapidly striking tiny pins against an ink ribbon to form letters and images from a matrix of dots—hence the name. The result was a pixelated, slightly smudged page of text that, while far from beautiful, was tangible proof that your computer was doing something productive. That was all that mattered.

The printers fed on continuous sheets of perforated paper, famously lined with holes on either side to guide the sheets through the machine. This “tractor feed” paper came in accordion-folded stacks, often requiring careful alignment and frequent realignment when the edges tore or the feed misbehaved. The paper itself had a unique tactile charm—it was flimsy, slightly waxy, and designed to tear neatly along its perforated edges. Tearing off the perforated strips became a ritual, oddly satisfying and weirdly symbolic of completing a task in the digital realm.

For many users in the 1980s, the dot matrix printer was their first experience with “desktop publishing,” a term that sounded impossibly sophisticated at the time. Kids printed school reports in a font that looked like digital chicken scratch. Small businesses cranked out invoices, mailing labels, and payroll sheets. Early adopters even used them to create primitive newsletters and greeting cards. The printers weren’t fast, and they certainly weren’t silent, but they were consistent. You could watch them labor across the page line by line, a visual and auditory confirmation that your data—abstract and invisible on the screen—was being etched into physical reality.

Of course, owning a dot matrix printer also meant a steady diet of ribbon cartridges and alignment headaches. The ribbons needed replacing regularly and were prone to drying out or smudging. Lines of text could become faint if the ribbon wasn’t feeding properly, and graphics—such as they were—often looked like ghostly approximations of clip art rather than anything truly recognizable. Still, it was hard to complain. The very idea that your home computer could interface with a machine to produce a document you could hold in your hands was, for the time, almost magical.

In a way, the dot matrix printer was the physical manifestation of early computing’s limitations and ambitions. It wasn’t beautiful, it wasn’t intuitive, and it rarely worked without effort—but it worked. It was reliable in a world where most technology felt experimental. Its design was unapologetically industrial, with beige plastic shells and awkward buttons, but that utilitarian look only added to its charm. When it screeched into action, it didn’t just print—it declared your presence in the digital frontier.

For kids who grew up with dot matrix printers, the sound of one in motion is burned into memory. It was the sound of book reports being finished the night before they were due. It was the sound of birthday banners made with ASCII art. It was the sound of progress, of productivity, of the future grinding out slowly, one dotted line at a time.

While these printers have long since faded from most desktops, replaced by quieter, faster, and far more capable alternatives, the dot matrix era represents something essential about the 1980s. It was a time when technology wasn’t hidden behind sleek glass panels or silent touchscreens. It was exposed—mechanical, physical, noisy, and interactive. It forced you to understand how things worked, to get your hands dirty, to troubleshoot with trial and error. In that way, the dot matrix printer was more than a gadget. It was a rite of passage.

6. The Electronic Typewriter – The halfway step between manual typewriters and word processors

In the 1980s, the electronic typewriter arrived like a quiet revolution on the desks of students, secretaries, and writers. It was a curious machine—firmly grounded in the legacy of the manual typewriter, yet peering cautiously toward the digital horizon. Often mistaken today for a simple relic, the electronic typewriter was, in fact, a critical evolutionary link between old-world mechanics and the emerging era of intelligent machines. It retained the soul of its predecessors—the click of keys, the clatter of letters onto paper—but it added features that seemed like science fiction to anyone raised on ribbon ink and correction fluid.

Unlike manual typewriters, which required pure finger force and offered no forgiveness for typos, electronic typewriters brought with them the first signs of automation and grace. Keystrokes were powered electrically, giving a smoother, quieter, and more consistent feel. Some models came with a small internal memory buffer, allowing users to see a few words or even an entire line on a tiny display before it printed—a concept that felt astonishingly modern at the time. Built-in correction systems became standard, using either correction tape or lift-off ribbons to remove mistakes with a quick tap of the “Correction” key. No more clumsy white-out. No more ripping out the page in frustration and starting over.

The most advanced models even allowed limited formatting capabilities. You could justify margins, center text, or create bold letters by typing over the same line twice. Some included spell-check features or could store short blocks of text in memory—useful for repeating addresses, signatures, or form responses. These capabilities, modest by today’s standards, were groundbreaking then. They represented a quiet shift in expectations. Typing was no longer entirely linear or irreversible. You could think, pause, adjust. The machine began to accommodate the writer, rather than forcing the writer to accommodate the machine.

For many people, the electronic typewriter was their first brush with user-friendly technology. It didn’t require manuals thick as bricks or the patience to learn DOS commands. You plugged it in, fed it paper, and began typing. It felt familiar but subtly more powerful. Offices adopted them eagerly, as they improved the speed and polish of correspondence. Students typed term papers with newfound ease. Aspiring novelists found a companion that offered consistency and clarity without the complexity of a full-fledged computer.

Still, despite their improvements, these machines were unmistakably typewriters at heart. They printed characters one at a time, directly onto paper, with no way to save a full document or revise it extensively. Once the ink hit the page, there was no going back. That tension between control and commitment was still there, but it was softened, refined. You could fix mistakes more easily, but you still had to think before you typed. It was writing as craft—deliberate, physical, and linear—but with a gentler learning curve.

In hindsight, the electronic typewriter represents more than just a transitional technology. It captures the spirit of the 1980s—an era defined by experimentation, adaptation, and the blending of analog grit with digital possibility. These machines were used in a time when information was just starting to flow faster, when offices were beginning to modernize, and when people were first experiencing what it felt like to have a machine work with them, not just for them.

By the late ’80s and early ’90s, the electronic typewriter began to fade from prominence as affordable personal computers and dedicated word processors took over. But for that brief window of time, it offered something unique: the reliability of the past merged with the promises of the future. It was the bridge between clunky permanence and digital fluidity, a stepping stone that helped a generation learn to write smarter before they learned to write digitally.

Today, you’ll find electronic typewriters mostly in storage closets, vintage shops, or nostalgia-soaked Instagram posts. But their role in the evolution of personal technology remains important. They were not just tools for typing—they were early ambassadors of convenience, design, and user experience. And for those who grew up with them, the gentle hum of the motor, the responsive touch of the keys, and the soft whisper of correction tape are not just memories—they are the echoes of a world learning, step by step, to go digital.

7. The Pocket TV – Tiny CRT screens that promised portable entertainment

In the 1980s, the very idea of watching television anywhere felt like a glimpse into the future. Not in the backseat of a car via a tablet or streamed on a smartphone in an airport terminal—those were dreams too distant to even imagine. No, in the age of antennas and appointment viewing, the notion of carrying a television in your pocket was astonishing. And yet, that’s exactly what the Pocket TV promised: a tiny, self-contained device with a miniature screen that delivered real-time broadcasts on the go. It was a marvel of miniaturization, a gadget that turned heads, sparked envy, and—more often than not—disappointed in glorious 1980s fashion.

The Pocket TV was not just a single product, but a genre of futuristic tech pursued by several major electronics companies. Sony led the way with its Watchman line, first released in 1982. Sharp, Casio, Panasonic, and others soon followed with their own compact offerings. These devices were marvels of engineering, housing fully functional cathode ray tube (CRT) displays in bodies no larger than a thick paperback. Some models were horizontal and clunky, others vertical and sleek, but all of them delivered on a singular, almost magical promise: television, anywhere.

The defining feature—and the biggest engineering hurdle—was the miniature CRT screen. Unlike modern flat displays, CRTs use an electron gun to project images onto a phosphorescent screen, which required bulky glass tubes and high-voltage components. Shrinking this technology down to fit in the palm of your hand without losing all image fidelity was a masterclass in compromise. The result was often a tiny, grainy picture with distorted colors, limited brightness, and narrow viewing angles. But none of that mattered. The fact that you could hold a functioning television in your hand, powered by AA batteries or a wall adapter, was enough to feel like a glimpse into the next century.

The antenna, often telescoping like a metal insect leg, was both essential and ridiculous. Without a strong analog broadcast signal, reception was fuzzy at best and pure static at worst. You often had to sit at just the right angle—arm stretched awkwardly toward the window, antenna fully extended and twisted skyward—just to catch a clear channel. Even then, the viewing experience was usually compromised by ghosting, noise, or sudden drops in signal. But again, these limitations were tolerated, even embraced. This was portable television. That it worked at all felt like victory.

In practice, the Pocket TV found its niche among commuters, travelers, and tech enthusiasts. Businessmen could catch the evening news on a train. Sports fans could sneak glimpses of live games at work. Some parents brought them along on long car trips, propping the screen between front seats to entertain restless children—an early, analog version of in-car entertainment. But just as often, they were conversation pieces. To own one was to say something: that you were forward-thinking, tech-savvy, and willing to trade fidelity for innovation.

There were even models that pushed the envelope further. Some included headphone jacks for private listening. Others boasted AM/FM radios, digital tuners, or rudimentary remote controls. In Japan, where miniaturization and consumer electronics were advancing rapidly, some models grew incredibly sophisticated, with higher-quality screens and better reception—though they remained niche even there. Despite their ambitions, these devices never crossed over into mainstream dominance, held back by technical limitations and the sheer impracticality of tiny CRTs in real-world use.

By the end of the 1980s and into the early ’90s, the rise of LCD technology began to signal the end of the Pocket TV as we knew it. The newer displays were flatter, lighter, more energy-efficient, and far easier to scale down. Eventually, handheld gaming devices, portable DVD players, and smartphones took over the dream of mobile entertainment, pushing the old CRT-based pocket televisions into irrelevance. The analog broadcast infrastructure they relied on would itself be turned off decades later, rendering the original devices virtually useless.

Today, Pocket TVs from the 1980s are collector’s items, quirky trophies of an era when engineers were pushing the limits of what was possible. They are reminders of a time when innovation was physical—you could feel it in the weight of the battery pack, in the satisfying click of the channel dial, and in the warm glow of the curved screen flickering in the dark. The technology may have been primitive by today’s standards, but the imagination behind it was boundless.

The Pocket TV didn’t just offer portable entertainment—it offered possibility. It hinted at a world untethered from living room walls and roof-mounted antennas. And though the image was small, blurry, and temperamental, it was enough to change the way people thought about television. It wasn’t just a box in the corner anymore—it was something you could take with you, even if it barely fit in your pocket.

8. The LaserDisc Player – The future of video… that barely made it past the ’80s

In the 1980s, when VHS and Betamax were battling for control of the home video market, another contender quietly entered the ring with an air of sophistication, futuristic flair, and dazzling audiovisual quality: the LaserDisc Player. Larger, shinier, and unquestionably more advanced in terms of performance, the LaserDisc seemed poised to redefine how people watched movies at home. Yet despite its technical superiority, it never truly crossed into the mainstream. It was the future of video—only it arrived too early, demanded too much, and faded out long before its potential was realized.

The LaserDisc itself was an imposing, beautiful thing: a 12-inch optical disc that looked like a vinyl record dipped in chrome. Unlike VHS tapes, which relied on magnetic tape to store data, LaserDiscs stored analog video and digital audio optically, read by a laser beam rather than physical contact. This innovation brought with it a range of jaw-dropping improvements: crisper picture quality, sharper colors, and stereo sound that could rival the movie theater experience of the time. For cinephiles, it was a revelation—no more fuzz, no more rewinding, no more worn-out tape degrading with every viewing.

The technology was groundbreaking. Developed jointly by MCA and Philips, the LaserDisc Player used a laser to read the disc’s surface, which significantly reduced wear and tear compared to tape-based formats. Early models hit the market in the late 1970s, but it was in the 1980s that the format began to find a niche audience. Its frame-by-frame accuracy and high-fidelity audio made it a favorite among film collectors, educators, and tech enthusiasts. It was even used in some classrooms and training programs, especially for interactive content—a primitive ancestor to DVD-based learning.

But for all its brilliance, the LaserDisc Player came with a host of drawbacks that kept it from achieving widespread popularity. First and foremost was its sheer size. The discs were enormous and fragile, requiring careful handling and plenty of storage space. A standard movie would often be spread across multiple sides or even multiple discs, requiring the viewer to get up halfway through to flip or switch the media. Some high-end players offered automatic disc-flipping, but these were expensive and still couldn’t compete with the convenience of just letting a VHS tape run to the end.

And then there was the cost. LaserDisc players were expensive—often hundreds of dollars more than a standard VHS unit—and the discs themselves were far pricier than tapes. Movies that sold for $20 or $30 on VHS could cost double or more on LaserDisc, which was a tough sell in a market driven by affordability. Additionally, the machines were not always user-friendly. Early models could be finicky, loud, and sensitive to dust or scratches on the disc’s surface. While the format did eventually evolve to include digital audio and features like chapter selection, these advancements arrived just as newer, more practical formats were emerging.

Another critical weakness was the lack of recording capability. Unlike VHS, you couldn’t use a LaserDisc to tape your favorite shows off TV or make home movies. This meant the format was relegated to commercial film releases only. In a decade when people were beginning to build home video libraries with taped TV shows, rental cassettes, and personal footage, this limitation severely undercut the LaserDisc’s appeal. It was built for movie lovers—but it didn’t fit the everyday viewing habits of the average household.

Despite these challenges, the LaserDisc carved out a devoted fan base. Collectors were drawn to the superior audio-visual experience, and many appreciated the format’s bonus content—years before DVD “extras” became a standard. Some LaserDiscs included commentary tracks, making-of documentaries, and behind-the-scenes footage, giving fans unprecedented insight into their favorite films. In fact, this model of supplementary material would go on to inspire the bonus features of DVDs and Blu-rays in later years.

Japan embraced the format more enthusiastically than most Western markets, with a stronger LaserDisc presence in households, karaoke systems, and educational tools. There, it hung on through the 1990s more robustly, becoming an iconic piece of consumer tech. In the U.S. and Europe, however, its market share remained a sliver of the video pie—too expensive for casual users, too cumbersome for the average living room.

By the mid-1990s, the writing was on the wall. The DVD, smaller, more durable, and digitally versatile, swept in and quickly became the standard for optical media. It borrowed many of the LaserDisc’s innovations—laser-based playback, chapter selection, bonus content—but wrapped them in a smaller, more accessible package. Within a few years, the LaserDisc Player became a museum piece, remembered fondly by tech enthusiasts and dismissed by most as a failed format.

And yet, to call it a failure misses the point. The LaserDisc Player was ahead of its time—too advanced, too elegant, and too expensive for a market still adjusting to the novelty of watching movies at home. It bridged the analog and digital worlds with grace, and its DNA lives on in every disc-based format that followed. For those who owned one, the whir of the disc spinning up and the smooth, clean picture on the screen represented not just entertainment, but possibility—a glimpse of how good home media could be.

Today, LaserDiscs and their players are collector’s items, treasured for their retro appeal and their place in the timeline of technological progress. They remind us that innovation doesn’t always win the race, but it often lays the track. And in the case of the LaserDisc Player, it left behind a shining, oversized legacy that still gleams with the promise of what could have been.

9. The Clapper – A “smart home” gadget before smart homes existed

In a time when the phrase “smart home” hadn’t even entered the average person’s vocabulary, one humble little gadget was already laying the groundwork for hands-free living: The Clapper. Introduced in the mid-1980s, this now-iconic sound-activated switch offered something that felt like science fiction—appliances you could control with nothing more than a clap of your hands. It wasn’t connected to the internet, had no app, and didn’t speak back, but The Clapper tapped directly into the futuristic fantasies of the time and made them real, affordable, and amusingly within reach of the average consumer.

To understand the cultural impact of The Clapper, you have to place it in the context of 1980s domestic life. Remote controls were still a novelty. Most people physically turned knobs or flipped switches to operate their devices. Automation was a luxury confined to the pages of science fiction or the domain of corporate tech demos. The Clapper changed that by offering a kind of minimalist wizardry. Plug it into an outlet, plug a lamp or radio into it, and suddenly your room responded to the sound of your hands. Two claps, and the lights would go off. Two more, and they’d come back on. It was empowering. It was playful. And for many, it felt like stepping into the future.

The Clapper was not a sophisticated machine by modern standards, but its inner workings were clever. It featured a microphone and analog sound pattern recognition circuitry capable of detecting the sharp acoustic signature of hand claps. What made it remarkable for its time was that it could distinguish those claps from other background noises—at least most of the time. It filtered sound through basic frequency thresholds, activating only when it heard two sharp bursts in rapid succession. There was even a sensitivity dial for fine-tuning, so it wouldn’t turn on every time a door slammed or someone laughed too loudly.

Yet part of its charm lay in its imperfections. The Clapper had a reputation for misfiring—either too sensitive or not sensitive enough. Users often found themselves clapping like maniacs to get it to respond, or they’d sneeze and accidentally turn the TV off. Dogs barking, thunder claps, even bursts of laughter could sometimes fool it. But people didn’t mind. If anything, it added to its personality. Like a quirky roommate, The Clapper didn’t always do what you expected, but it was trying its best. And in a decade filled with technical firsts and awkward early tech, its unpredictability only made it more memorable.

The device skyrocketed in popularity thanks to its unforgettable advertising campaign. Late-night infomercials and daytime TV ads drilled its catchy slogan into the American psyche: “Clap on! Clap off! The Clapper!” The jingle became so famous that even people who had never owned the product could recite it by heart. The commercials featured glowing testimonials from elderly users, busy moms, and gadget-happy dads, all clapping joyfully as their appliances blinked obediently. It was an appealing fantasy: no cords, no remotes, no moving from your chair. Just clap and control your world.

The Clapper was especially popular among the elderly and people with disabilities. Its simplicity made it accessible, and it offered a modest but meaningful boost to independence. Instead of fumbling in the dark for a lamp switch or struggling to reach a plug, users could simply clap their hands. In a quiet way, The Clapper was ahead of its time in terms of inclusive design—offering practical functionality to people who often got left behind in the race toward modern tech.

From a manufacturing and market standpoint, The Clapper was a stroke of genius. It was low-cost to produce, easy to package, and required no technical setup. You didn’t need to understand electronics to use it—just an outlet and your hands. As such, it became a popular gift item, particularly around the holidays. It was perfect for those “What do I get them?” moments: quirky but useful, gimmicky yet grounded in real utility. Over time, it also became a pop culture staple, parodied on sketch shows, sitcoms, and stand-up routines.

The Clapper did attempt to evolve. Later versions included features like three-clap control for separate functions, noise filtering enhancements, and even remote controls. But by the mid-1990s and into the 2000s, the home tech landscape had started to shift dramatically. The rise of digital assistants, motion sensors, remote-controlled outlets, and eventually smartphone integration meant The Clapper’s days were numbered. It simply couldn’t compete with the flexibility, precision, and integration of newer tech. Still, many homes hung on to their Clappers for years—if not for utility, then out of affection.

Today, The Clapper is both a nostalgic artifact and a symbol of an era when technology felt more like a magic trick than a surveillance tool. It didn’t track your data, didn’t require updates, and didn’t ask for permissions. It just responded, somewhat stubbornly, to one of the oldest gestures in the human toolkit. In many ways, The Clapper is the analog ancestor of today’s smart plugs and home automation systems. It represented the desire to make our living spaces more interactive and responsive, and it did so with elegant simplicity.

You can still buy modern versions of The Clapper, and collectors often seek out vintage units for their retro appeal. They serve as a reminder that technology doesn’t have to be complex to feel magical. Sometimes, all it takes is a little box, a clever circuit, and the sound of two claps echoing through a room to remind us how far we’ve come—and how much joy there can be in the simplest innovations.

10. The Cassette Answering Machine – Your voice mailbox in a little whirring box

Before the age of digital voicemail, text messages, and real-time notifications, there was one device that stood sentinel beside nearly every landline phone in the 1980s: the cassette answering machine. Often overlooked today, this mechanical marvel once served as your digital receptionist, memory bank, and lifeline to the outside world—all packed into a modest, boxy device with tiny spinning reels and blinking red lights.

For many, the answering machine was their first real taste of asynchronous communication. You no longer had to be home to catch an important call. You didn’t have to ask your roommate, child, or neighbor to take a message. Instead, you had a machine that would politely greet your callers, record their voices, and save their words on magnetic tape for you to replay at your leisure. It was independence. It was control. And it was deeply personal. The messages it held were often voices you longed to hear—family, lovers, business prospects, friends—and they were stored on a fragile strip of tape that could feel like gold.

The 1980s versions of these machines relied primarily on microcassettes or standard compact cassettes. There were two tapes: one for outgoing messages (your custom greeting) and one for incoming recordings. You’d press the red “Record” button and speak into a tiny built-in microphone to set up your greeting—something as simple as “Hi, I can’t come to the phone right now,” or as elaborate as a mini stand-up routine. The greeting would play back to each caller, after which the machine would beep and begin recording their message on the other tape.

The process was mechanical and fascinating. You could often hear the soft whirring of the tape rewinding, clicking, and resetting between messages. Some models had little see-through windows so you could watch the tiny reels spinning, as if performing a private ritual. Playback required rewinding and fast-forwarding with chunky buttons, often leading to some guesswork and a lot of patience. If you wanted to skip a message, you’d have to hold the fast-forward button down and squint at the tape to guess when the next one started. If you rewound too far, you’d hear part of your greeting again. But these imperfections were part of the experience.

There was a real human element to how people used these machines. Greetings became a creative outlet. People sang them. They made movie spoofs. They layered in background music from a stereo. Others went the opposite route and tried to sound ultra-professional, especially during the heyday of networking and self-branding. Your outgoing message was your audio handshake—a chance to set the tone before a caller even said a word.

But answering machines weren’t just about communication; they were also about suspense and drama. Coming home and seeing that blinking light meant someone had reached out. You never quite knew who it was until you pressed play. There was anticipation in that moment, a thrill not unlike opening an old-fashioned letter. Messages could contain anything: good news, bad news, a confession, an apology, a business opportunity, or even a hang-up in which someone said nothing at all. In that way, answering machines became tiny audio time capsules of human interaction.

There were even social customs built around them. People would screen calls by listening silently to incoming messages in real time, choosing whether to pick up the phone mid-recording—a kind of analog call screening. Some households developed etiquette rules: “Don’t record over Dad’s messages,” or “Play your messages privately.” Others got a little paranoid, rewinding and re-listening to important calls multiple times just to catch the nuance in someone’s voice.

As with most tech of the ’80s, the cassette answering machine was far from flawless. Tapes wore out. Messages got garbled. Sometimes you’d record over the wrong section and lose something irreplaceable. The machines could jam or eat the tape entirely, producing a mess of twisted plastic ribbon that had to be carefully untangled with a pencil and prayer. If you lost power, some models would reset and erase everything. Still, people trusted these devices. They were reliable enough, and in a world without cloud backups or smartphones, they were your best hope of staying connected when you couldn’t answer the phone yourself.

Despite their mechanical simplicity, answering machines had a profound cultural impact. They changed how people communicated. They allowed for new forms of etiquette, expectation, and even anxiety—what we now call “missed call stress” or “voicemail dread.” In movies and TV shows, the answering machine was often a plot device. Characters would come home to pivotal revelations: a job offer, a breakup, a twist in the story—all waiting patiently on magnetic tape. They added emotional weight to the mundane act of pressing “play.”

By the 1990s, digital versions began replacing their analog ancestors, eliminating the tapes and replacing the gears and motors with flash memory. Eventually, mobile phones and network-based voicemail made them obsolete altogether. But for a time—especially in the 1980s—the cassette answering machine wasn’t just a gadget. It was a trusted companion, a memory keeper, and a small, humming witness to daily life.

Today, they survive in thrift stores, collector’s shelves, and vintage films that immortalized their beeps and buzzes. But for those who lived through their heyday, cassette answering machines will always represent a warm and tangible slice of the analog past—a time when technology wasn’t invisible or instant, but physical, audible, and just a little bit magical.

Conclusion: Echoes of Innovation from a Bygone Era

The gadgets of the 1980s were more than just technological curiosities; they were stepping stones toward the hyper-connected, digital world we live in today. Each device, from the trusty Walkman to the stubborn Clapper, carried the weight of innovation and imagination in its plastic shell. They were imperfect, noisy, often bulky, and yet they brought with them a sense of wonder—a glimpse of what the future might hold.

These relics of a not-so-distant past remind us that progress isn’t always sleek and silent. Sometimes it hums, buzzes, whirs, and rewinds. They taught an entire generation how to engage with technology in a hands-on, tactile way, forming habits and experiences that would shape how we interact with machines today. And while they may now gather dust on shelves or live on only in memory, their spirit persists in every pocket-sized computer, voice assistant, and smart home device we use now without a second thought.

Revisiting these obsolete marvels isn’t just an exercise in nostalgia—it’s a reminder of how far we’ve come, and how thrilling the journey has been. These gadgets were the awkward, lovable ancestors of our digital age, and they deserve a proud place in the story of technological evolution. So here’s to the clicks, claps, tapes, and tiny screens of yesteryear. They may be obsolete, but they will never be forgotten.

Leave a comment