Introduction: A Time Before Wi-Fi

There was a time—not so long ago, really—when the phrase “you’ve got mail” meant walking to a physical mailbox. When scrolling meant flipping through the pages of a dog-eared magazine, and the only kind of “streaming” was the trickle of water from a backyard hose on a hot summer day. This was the 1980s, a decade that now feels like a relic from another planet for anyone raised in the age of smartphones and instant internet access.

The world before Wi-Fi was quieter, slower, and often more physically grounded. It was a time of tactile experiences—turning knobs, pushing buttons, popping cassette tapes into boom boxes, and pulling out drawers filled with Kodak prints. The idea that you could press a button and instantly connect with someone across the world, download a movie in minutes, or get the answer to any question without leaving your couch would have seemed like science fiction. And yet, somehow, life still worked—beautifully, imperfectly, and memorably.

In the 1980s, information didn’t come with a Google search. You had to go out and find it. If you wanted to learn about dinosaurs or space or ancient Egypt, you pored over encyclopedias or convinced your parents to take you to the library. If you needed to know what time a movie started, you didn’t check an app—you called the theater’s recording and listened carefully. Finding a friend’s phone number meant opening a paper phone book, and keeping up with trends required watching MTV, reading Tiger Beat, or eavesdropping at the school lunch table.

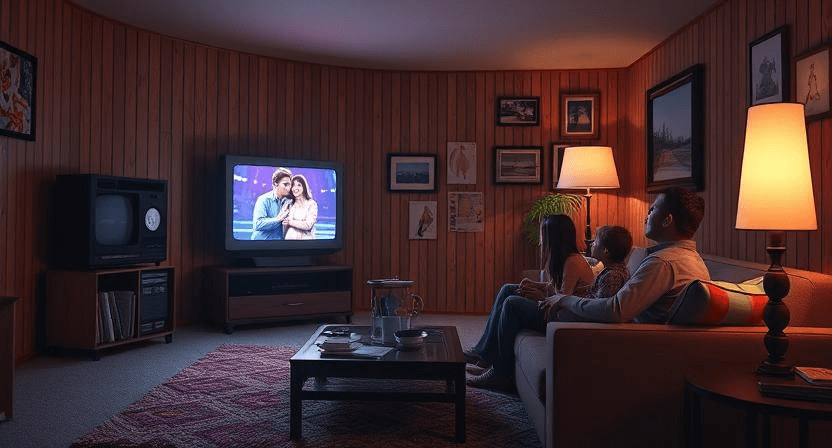

Entertainment was a communal activity, not an endless scroll done in isolation. Families gathered around one television set, choosing a program from whatever was playing live. Missing an episode of your favorite show meant waiting for reruns or missing out entirely. And yet, the shared experience of “tuning in” at a specific time gave television a kind of cultural gravity that’s hard to replicate today. If a major event happened, like the Challenger launch or the finale of MASH*, the entire nation experienced it together, in real time.

Even boredom was different. Today’s boredom is a pause between notifications or the moment your phone dies. But in the 1980s, boredom could stretch for hours—and it was in those long, unscheduled gaps that imagination took over. Kids invented elaborate games, built forts out of couch cushions, biked aimlessly through neighborhoods, and got lost in books they picked up just because the cover looked cool. Adults had their own analog diversions: crossword puzzles, evening strolls, tinkering in the garage, or chatting over the fence with neighbors.

This isn’t to say the 1980s were a utopia—far from it. There were limits and inconveniences that today’s technology has solved beautifully. But there was also a richness in the slowness, a tactile delight in doing things with your hands, and a kind of intimacy in communication that has largely been eroded by the speed and volume of the digital world. Conversations happened face-to-face or over rotary-dial phones. Friendships were built through shared experiences, not likes and comments. Photos were taken thoughtfully, because film wasn’t cheap. News traveled slower, but maybe hit harder, because it wasn’t buried in an endless feed.

As we look back on life before the internet, it’s not about romanticizing the past or pretending every aspect of analog life was better. It’s about remembering what it felt like to live fully offline, to occupy space with your whole attention, and to connect with people and the world in more tangible ways. The 1980s may have lacked Wi-Fi, but it was a decade rich with connection, creativity, and real-world engagement—the kind that doesn’t require a screen.

Entertainment in the Analog Age

Long before we had infinite entertainment at our fingertips, there was the thrill of scarcity—the excitement of having to wait, plan, and truly savor each experience. In the 1980s, entertainment wasn’t available on demand. You couldn’t skip commercials, binge-watch a show, or shuffle an endless playlist of songs. What you had instead was anticipation, community, and the magic of shared moments. Entertainment was something you carved out time for, not something that followed you around in your pocket.

Television was king, but it wasn’t an all-access monarch—it made you play by its rules. Families often had a single TV in the house, and it was a negotiation every evening to decide what would be watched. Channel surfing meant turning a dial or, if you were lucky, clicking a chunky plastic remote with satisfying resistance. Networks aired shows at fixed times, so if you missed your favorite episode of Knight Rider, Cheers, or The Cosby Show, you were simply out of luck. You’d have to wait months for a possible rerun or hear your friends talk about it at school while you nodded along, faking familiarity. That scarcity gave television an urgency and collective feel—it wasn’t just entertainment; it was a cultural event.

The introduction of cable TV and networks like MTV changed the game entirely. Suddenly, music videos became part of the daily rhythm, and for teenagers, MTV was more than just a channel—it was a portal to youth culture, fashion, attitude, and rebellion. Watching your favorite band’s new video premiere wasn’t just fun; it was a social currency. You talked about it the next day, memorized the lyrics, and maybe even tried to mimic the style. It was visual storytelling in its rawest form, and it defined much of what the decade looked and sounded like.

For movie lovers, entertainment meant going to the theater or renting a VHS tape. Blockbuster nights were events in themselves—wandering through the aisles, reading the backs of plastic cases, and arguing with your siblings over what to pick. The selection wasn’t limitless, and that was part of the charm. You might end up watching Ghostbusters or The Goonies for the third time not because you couldn’t find anything else, but because those movies became comforting companions. Rewatching was a joy, not a fallback. And if you were lucky enough to own a few tapes? You probably wore them out.

Music was another realm entirely. There was a ritual to it—flipping through record store bins, saving up allowance for a new cassette, or timing your finger perfectly to hit “record” on your boombox when your favorite song came on the radio. That fuzzy, half-missed intro on your homemade mixtape didn’t ruin the song; it made it yours. Music felt earned. You couldn’t skip tracks with a tap. You listened from beginning to end, reading the liner notes, learning lyrics by heart, and rewinding with a pencil when the tape got chewed up. Albums weren’t just sound—they were objects of affection, and often of obsession.

And then there were video games, still in their early glory days. While modern consoles offer cinematic realism and immersive online play, the 1980s brought people together at the arcade. Walking into one was like entering a neon-lit temple of beeping, buzzing possibility. You fed quarters into machines like Pac-Man, Donkey Kong, Galaga, and Defender, hoping for a high score and maybe a moment of neighborhood fame. Home systems like the Atari 2600 and later the Nintendo Entertainment System began to bring that magic indoors, but the joy was still tactile—joysticks clicking, cartridges blowing dust, screens flickering in the dark.

Entertainment in the 1980s wasn’t just about the content—it was about the experience. You had to make time for it, make space for it, and most of all, be present for it. There was no background streaming while doing chores, no skipping the slow parts. If something was boring, you lived with it. If it was amazing, you remembered it. The analog age had a way of anchoring joy in the physical world, and in that grounding, every song, show, or movie felt like it mattered a little more.

Social Life and Communication

Long before text messages and status updates became our default mode of staying in touch, communication in the 1980s was a deliberate act—more personal, more effortful, and often more meaningful. There was no Facebook, no WhatsApp, no instant messaging. If you wanted to talk to someone, you had to physically show up, pick up the phone, or write a letter. Human connection wasn’t mediated through screens or curated feeds—it happened in real time, often with awkward silences, real laughter, and the subtle choreography of body language.

The telephone was the lifeline of social life, especially for teens. Every household had a landline, usually stationed in a high-traffic area like the kitchen, with a cord that may or may not stretch far enough for a private conversation. If you were lucky, your family had a long, spiraling phone cord that allowed you to retreat around the corner or into a hallway for just a sliver of privacy. You learned the art of pacing during calls, twirling the cord absentmindedly as you talked for hours about nothing and everything. And God help you if someone picked up the other phone in the house mid-conversation—eavesdropping was an unavoidable hazard.

For parents, the phone was a scheduling tool and social bridge. Birthday parties were planned through actual conversations. You called ahead when you were running late. You asked for someone by name, then patiently waited while they were summoned to the receiver. Voicemail was still a novelty—answering machines clicked and whirred, playing recorded messages that sometimes felt more intimate than the call itself. And the dreaded busy signal? That sound was the drumbeat of persistence, especially when calling into radio stations or trying to reach your crush after school.

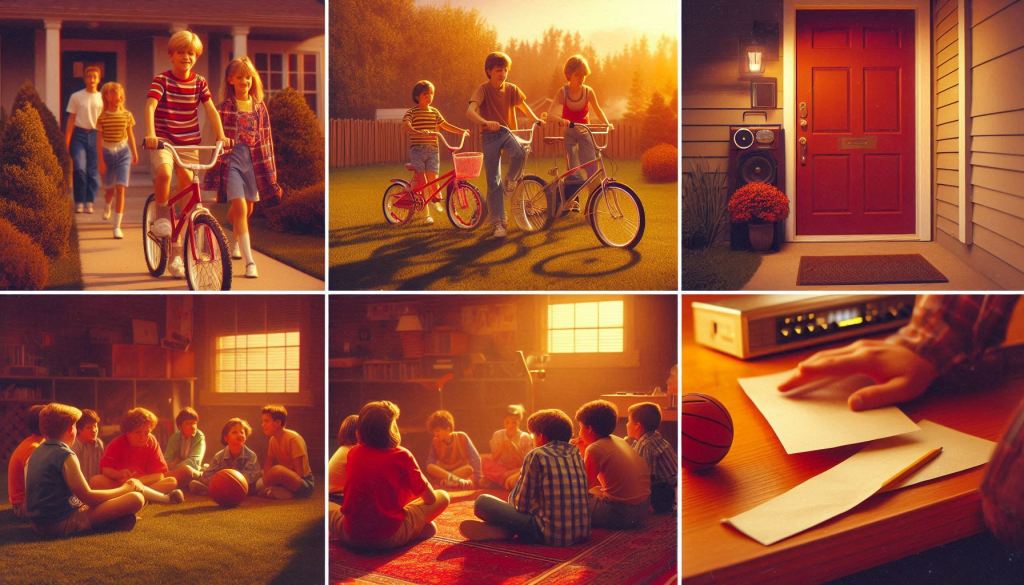

But the most powerful form of communication—the one that solidified friendships and burned stories into your memory—was face-to-face interaction. Kids didn’t text to make plans. They showed up. They knocked on doors. They asked, “Can you come out and play?” Social lives were built on proximity and spontaneity. You knew who was home because their bikes were piled on the front lawn. You knew where to go because you heard the music blasting from a backyard, or saw the garage door open with a group of kids gathered around a new toy, a stereo, or a basketball hoop.

At school, communication took on its own analog charm. There was an entire unspoken language to passing notes in class—folded into elaborate shapes, passed hand-to-hand like secret treasure. These weren’t throwaway messages. They were keepsakes. A note might say something as simple as “Do you like me? Check yes or no,” but it carried the emotional weight of a love letter. Friendships were sealed in whispers and scribbles, not emojis.

Social circles formed around shared experiences, not shared content. You bonded over the TV shows you all watched the night before, the new song you heard on the radio, or the time someone did something ridiculous on the school bus. There was no algorithm to feed you who or what to care about—you figured it out together. Rumors spread in the cafeteria, not through group chats. Jokes had to land in real time. Awkward moments couldn’t be deleted or edited—they simply became part of the memory.

Even long-distance communication had a ritualistic quality. Writing letters—actual, handwritten letters—was a common way to stay in touch with cousins, pen pals, or friends who had moved away. You took time with your words. You chose your stationery. You waited days, sometimes weeks, for a reply, and when it arrived, it felt like a gift. Receiving a letter in the mail meant something—it was a piece of someone’s world sent across time and space, and you held it in your hands.

Social life in the 1980s was far from perfect. It could be exclusive, cliquish, and at times isolating. But it was also deeply rooted in physical presence and intentional effort. You couldn’t hide behind a username. You had to show up, speak up, and look people in the eye. Friendships weren’t built by liking photos—they were built by sharing real time in real places, one moment at a time.

In a world without the internet, connection required more work—but it often yielded deeper rewards. You didn’t have hundreds of digital acquaintances. You had a handful of real friends. And for most people who grew up in that era, those bonds are still among the strongest they’ve ever known.

Information and Learning

In the 1980s, knowledge was not a matter of a few keystrokes or a shouted question to a digital assistant. If you were curious about something—how volcanoes formed, who won the World Series in 1962, or how to bake a cake from scratch—you had to search for the answer, physically and often with some degree of determination. Learning wasn’t instant. It was a process, sometimes tedious, sometimes thrilling, but always grounded in effort and discovery.

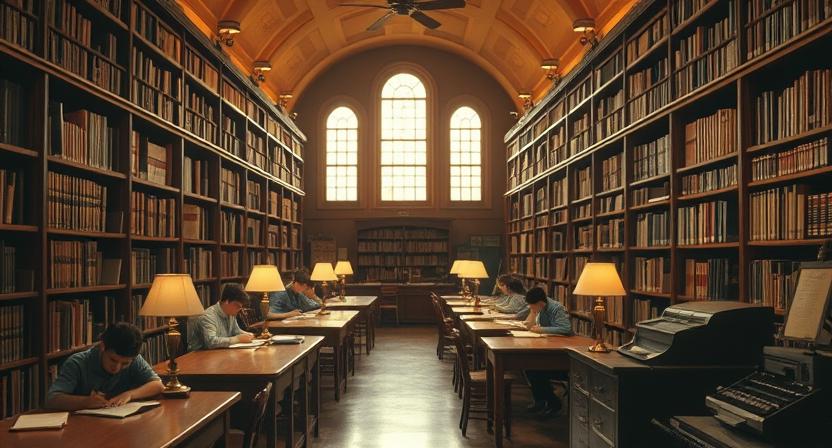

The library was the cornerstone of information. Whether at school or in the community, libraries were hushed, almost sacred spaces where answers lived on shelves instead of servers. The journey to understanding something new often began with the card catalog—a long drawer filled with index cards, each one typed or handwritten, listing a book’s title, author, and location in the Dewey Decimal System. Finding the right card felt like cracking a code. Then came the hunt—strolling through narrow aisles, brushing your fingers along the spines of books, pulling one out that seemed promising. It was tactile, time-consuming, and deeply satisfying.

And then there were the encyclopedias. Every classroom and many homes had a full set of these hefty volumes, often purchased from door-to-door salesmen or through special installment plans. Encyclopedias were the original Google: orderly, authoritative, and beautifully illustrated. They came in alphabetical volumes, and if you wanted to know about dolphins, you flipped to “D” and immersed yourself in a few dense pages of text. You didn’t get hyperlinks. You got context. And you didn’t stop at one article—chances are you’d start with dolphins and, twenty minutes later, be reading about dirigibles or the Dutch Golden Age.

Learning in the 1980s was also about curated content, not user-generated noise. You trusted the books in your school library because someone had chosen them carefully. You learned from teachers who stood in front of chalkboards, pointing with yardsticks, underlining important facts in textbooks that smelled of pencil shavings and crinkled plastic covers. If you needed to do a report on a country or a famous person, your tools were books, magazine clippings, and whatever you could find on microfilm if your library was well-equipped. There was a pride in cobbling together a project from these pieces—carefully hand-writing paragraphs or, if you had access to a typewriter, pecking out each line with no backspace key to save you.

Television and print media also played huge roles in how people learned about the world. The evening news—watched live on one of just a few channels—was a daily ritual in many households. You didn’t scroll headlines; you sat down and absorbed them in full. Anchors like Dan Rather and Peter Jennings were more than personalities—they were voices of authority, trusted interpreters of global events. And for kids, learning often snuck in through programming like Reading Rainbow, 3-2-1 Contact, or Schoolhouse Rock!—which turned educational content into catchy, unforgettable tunes.

Magazines and newspapers were another major source of information. You subscribed, or picked them up at the grocery store, and once they were in your hands, they stayed there. You folded them under your arm, tore out articles to tape on your bedroom wall, and re-read your favorites until the pages curled. Whether it was National Geographic, TIME, Teen Beat, or Popular Mechanics, magazines fed your curiosity one glossy issue at a time.

And let’s not forget the human network—asking parents, teachers, neighbors, or older siblings when you wanted to know how something worked. Before the internet, people were repositories of knowledge. If your dad knew how to fix a lawnmower or your aunt could bake the perfect pie, they became your search engines. Information was passed down, shared, and demonstrated in person. It was slow, yes, but it was rich—rooted in relationships, memory, and human warmth.

In today’s world, where knowledge is instant and omnipresent, it’s easy to forget the thrill of the hunt that defined learning in the 1980s. The information you found felt earned. You didn’t absorb it passively—you had to seek it out, decode it, and often discuss it with others. It was a slower way of learning, but in many ways, a deeper one. Because when you had to work for the answer, you were more likely to remember it.

Free Time and Hobbies

In the 1980s, free time wasn’t something you scrolled through—it was something you stepped into. Without smartphones, apps, or notifications constantly vying for attention, time away from school or work opened up like a blank page. It was up to you to fill it, and fill it we did—with movement, creativity, imagination, and connection. The rhythm of life was slower, and in that space between obligations, people of all ages learned the simple but profound joy of doing things for their own sake.

For children and teens, unstructured time was sacred. The moment the last school bell rang or the Saturday morning cartoons ended, kids flooded the streets and backyards like a seasonal migration. You didn’t text your friends to meet up—you showed up. You knocked on doors, rang doorbells, or simply looked for the telltale pile of bikes in someone’s yard, a sure sign that the gang had assembled.

Play was dynamic, organic, and usually happened outdoors. In the suburbs and small towns, kids would spend hours on their bikes, treating neighborhoods like racetracks and adventure zones. The ride itself was the destination. You might head to the local 7-Eleven for a Slurpee, race through a construction site (even though you weren’t supposed to), or just explore wooded areas, pretending to be on a quest or mission.

There were no structured “playdates”—just freeform exploration. Games like tag, kickball, Red Rover, or Mother May I? were organized on the fly, with rules that changed mid-game and debates that could last longer than the game itself. You might spend an afternoon turning a fallen branch into a sword or a pile of scrap wood into a secret clubhouse. Imagination wasn’t optional—it was essential.

Even in cities or apartment complexes, play found a way. Sidewalk chalk transformed concrete into worlds of color and creativity. Jump ropes slapped rhythmically against the ground, double-dutch chants echoing through alleyways. Ball games adapted to every available surface, from stoops to handball courts to chain-link fences. The world was a playground, and boredom wasn’t solved by screen time—it was solved by invention.

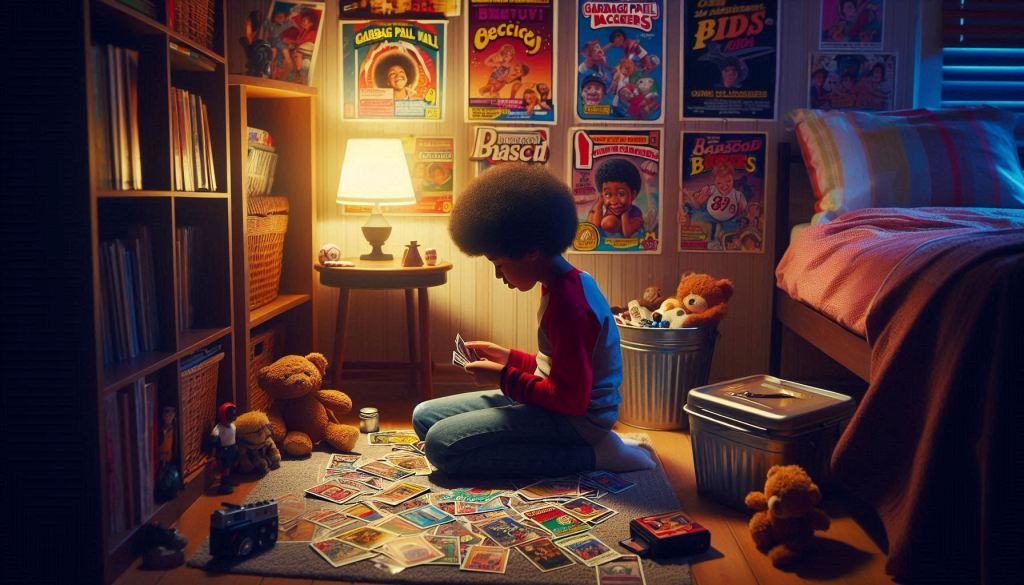

When the weather turned or the sun went down, attention turned indoors. That’s when hobbies came alive. Many kids were collectors. You might collect Garbage Pail Kids, baseball cards, Smurfs, erasers, rocks, stickers, or bottle caps. Each collection had its rituals: sorting, organizing, trading, and bragging. There was always the hope of finding that one rare item, and the sheer tactile joy of holding your treasures in your hands.

Creative hobbies flourished, often encouraged by the ubiquitous TV commercials that marketed everything from Spirographs to Easy-Bake Ovens. You could spend hours making friendship bracelets, building elaborate LEGO creations without a single instruction sheet, or using Shrinky Dinks and Lite-Brites to turn ordinary afternoons into miniature art shows. Model kits—cars, airplanes, ships—required careful gluing and painting, often with help from a parent or older sibling. It wasn’t about speed or convenience; it was about the process, the patience, the sense of achievement.

Books were constant companions. With fewer entertainment distractions, reading wasn’t framed as homework or obligation—it was escape, it was immersion. Libraries were portals, and trips to the Scholastic Book Fair were events you circled on the calendar. Whether you were a fan of Nancy Drew, Encyclopedia Brown, Choose Your Own Adventure, or Stephen King (for older kids and adults), books were treated with reverence. You dog-eared pages, passed favorites among friends, and stayed up late reading under the covers with a flashlight.

Television and music, of course, had their place. But they weren’t background noise—they were events. You might spend a Saturday afternoon taping songs off the radio, finger poised on the “record” button, trying to avoid capturing the DJ’s voice. Making a mixtape was an art form and a declaration—an expression of who you were, what you loved, and who you hoped to be. Meanwhile, adults enjoyed their own rituals: putting on a record after dinner, flipping through stacks of vinyl, selecting the perfect mood.

Board games were another staple of family life. Monopoly, Sorry!, Life, and Clue all made regular appearances on kitchen tables. Playing a board game wasn’t just entertainment—it was interaction. You negotiated rules, tested strategies, and sometimes, yes, flipped the board in frustration. It brought people together in a way few digital games can replicate.

Adults, too, had hobbies that provided creative and emotional sustenance. Gardening was not just a chore—it was a quiet, rewarding relationship with the seasons. People built birdhouses, refinished furniture, or dabbled in macramé. Others joined bowling leagues, knitting circles, amateur theater troupes, or classic car clubs. Time spent on these pastimes wasn’t tracked or monetized. It was about joy, expression, and mastery over something real.

There was also a cultural value in solitude. You could be alone without being lonely. You might sit by a window and sketch. You could lie on the carpet listening to a cassette from beginning to end, letting each song land. You might journal, daydream, or simply stare out the window and watch the world go by. These quiet, interior experiences were part of the rhythm of life—unhurried, undistracted, deeply human.

In hindsight, the hobbies of the 1980s may seem small by today’s standards—modest in scope, analog in nature. But they were rich in texture and often profoundly formative. They taught patience, creativity, social skills, and how to find satisfaction in simplicity. In a world that didn’t demand constant productivity or connectivity, doing something for the sheer love of it was more than enough.

Shopping and Commerce

In the 1980s, shopping wasn’t something that happened automatically or passively—it was something people did. It was an event, a routine, a social occasion, and often even a kind of ceremony. Unlike today, where transactions are silent, instant, and often invisible, shopping in that pre-digital decade had a sound, a smell, a feel. It was deeply physical. You didn’t click. You touched. You didn’t scroll. You wandered. The simple act of buying something took time, effort, and attention. And in that effort lay its meaning.

For many, the crown jewel of shopping in the 1980s was the American shopping mall. Not just a collection of stores, the mall was a complete cultural ecosystem. Teens flocked there after school and on weekends, not necessarily to spend money, but to be part of the scene. There was an energy to the mall, a hum of movement and music, of laughter echoing through tiled corridors and the faint scent of cinnamon rolls and cologne hanging in the air. Chain stores like The Limited, B. Dalton Bookseller, RadioShack, and Sam Goody were more than just retail outlets—they were cultural landmarks. Inside these stores, you discovered what was new, what was cool, and what everyone would be talking about on Monday at school. You’d thumb through vinyl albums or cassette tapes, try on stonewashed jeans in front of a three-way mirror, or gawk at the novelties in Spencer’s—some of them risqué enough to feel like forbidden territory. Shopping was social currency. If you bought something, great. If not, just being there was enough.

The mall food court was its own world—bright, loud, and busy. Teenagers shared giant sodas and greasy pizza slices. Parents sat and sipped coffee while their kids devoured soft pretzels. Workers on lunch breaks grabbed Styrofoam containers of Chinese food or chicken nuggets from neon-lit counters. No one was on a phone. Conversations happened face to face. People watched other people, not screens.

Outside the mall, shopping remained an intimate, local experience. There were still plenty of mom-and-pop stores on Main Street or tucked into neighborhoods—places that had been there for decades. The butcher knew your name. The pharmacist remembered your last prescription. The clerk at the corner store would ask how your grandma was doing. You weren’t just a customer. You were part of the life of the store, and the store was part of the life of your town. Everything about it had a pace. You waited your turn at the deli counter. You watched prices get punched in by hand on the register. You counted out coins from your pocket. There was no self-checkout. There was no rush.

Grocery stores had a certain predictability and comfort. You walked the same aisles every week, knew exactly where the cream of mushroom soup or your favorite cereal was stocked. Kids rode in the carts or begged for sugary cereals their parents rarely allowed. The crinkling of paper bags, the beep of a price scanner, the flick of the cashier’s wrist as she pulled items down the conveyor—these were the sounds of everyday life. Coupons were physical slips of paper, carefully clipped from the Sunday paper and organized in envelopes. People carried handwritten shopping lists and crossed things off in pencil as they filled their carts. It wasn’t efficient in the modern sense, but it was tangible, communal, and oddly satisfying.

Long before online ordering, catalogs brought distant shops into your living room. When the Sears or JCPenney catalog arrived in the mail, especially during the holiday season, it was a Big Deal. Families would flip through the hundreds of pages together, making notes, circling toys or clothes, daydreaming about what might be under the tree in a few weeks’ time. There was something almost sacred about filling out the little order form, calculating shipping costs, enclosing a check, and mailing it away. And then came the waiting—a long, slow anticipation that gave each delivery the weight of magic. When the package finally arrived, wrapped in plain brown paper or bearing the bright logo of the brand, it felt earned. The waiting was part of the joy.

Money had a different presence in the 1980s. Transactions were mostly done in cash. Dollar bills were counted by hand, coins rattled in pockets or purses, and every purchase felt real because you physically handed something over. Checks were used frequently, especially for larger or regular payments, and balancing your checkbook was a monthly ritual for millions of adults. Credit cards, while growing in popularity, were still used more cautiously. The credit card machine made that unmistakable “ka-chunk” sound as the carbon paper was pressed over your card’s embossed numbers. There was no instant approval, no tap-to-pay. Everything took a moment. And those moments made you think twice.

In neighborhoods across America, garage sales were their own kind of marketplace. On sunny Saturday mornings, families set up tables on their driveways and unfolded blankets across their lawns, displaying everything from used toys to old books, clothing, lamps, puzzles, and VHS tapes. You’d walk around with a couple dollars in your hand, looking for treasure. A rusty tricycle, a bin of Matchbox cars, a faded board game with half the pieces missing—everything held the possibility of a story. Kids learned to haggle. Parents taught their children the difference between junk and a bargain. There was something hopeful in these sales—this idea that what no longer served one person might bring joy to someone else.

Flea markets and swap meets took that experience and turned it up a notch. Rows of folding tables filled with trinkets, bootleg cassette tapes, homemade crafts, strange gadgets, tools, knockoff sunglasses, and antique furniture offered an endless sense of discovery. It was messy, spontaneous, and uniquely democratic. Anyone could sell, anyone could buy. It didn’t matter who you were or where you came from—everyone was there to browse, to chat, to find a deal. It was loud, lively, and human in every possible way.

Shopping in the 1980s was not simply about getting things—it was about being somewhere. It was about spending time with your mom at the fabric store while she picked patterns and you played with the zippers and buttons. It was about laughing with friends in the changing room, trying on the same ridiculous outfits, and swearing you’d all wear them to school on the same day. It was about taking your allowance to the toy store and standing in front of the Star Wars figures for half an hour, debating whether to get Boba Fett or Darth Vader. It was about moments—moments you felt, because they weren’t rushed and they weren’t virtual. They happened in real space, with real people, in real time.

The commerce of the 1980s wasn’t always convenient. You had to go out in the rain. You had to wait in line. You sometimes got home and realized you bought the wrong thing. But it was alive. It was shared. And in the absence of algorithms and ads that followed you everywhere, it left room for surprise, for wandering, for connection. You didn’t just shop. You participated in a kind of everyday theater—a place where time slowed down, where value was measured in more than dollars, and where a simple purchase could become a lasting memory.

Family Time and Home Life

In the 1980s, home was more than just a place you returned to at the end of the day. It was the center of life. The backdrop to everyday rituals. The stage on which family bonds were built, strained, and strengthened. Without smartphones, streaming services, or the endless distractions of the internet, people turned inward—toward each other. Family time wasn’t scheduled or curated. It just happened, organically, through shared spaces and daily rhythms that were often unremarkable in the moment but, looking back, feel full of warmth and meaning.

Evenings were the true heart of family life. After dinner, the house didn’t scatter into separate corners with headphones and screens—it gathered. The TV, a large box encased in wood or plastic and often positioned like a shrine in the living room, brought everyone together. Whether it was “The Cosby Show,” “Family Ties,” “Cheers,” or “Knight Rider,” families watched the same programs at the same time. And if you missed it, that was it—there was no replay, no on-demand. Everyone had their favorite night of the week when “their show” was on. The anticipation was part of the experience. Families arranged their evenings around those broadcast schedules, and sitting together on the couch, passing a bowl of popcorn, making comments during commercial breaks—these were small but binding moments.

Beyond television, games were a major part of family time. Board games like Monopoly, Life, and Clue came out after dinner, spread across the dining table that still had crumbs from dessert. Card games like Uno or Go Fish were quick, familiar favorites. Puzzles were common, too—a thousand scattered pieces that might take a week to finish, laid out on a coffee table where a family could return, piece by piece, day by day. There was talk. There were jokes. There was arguing over the rules and laughing at mistakes. But most of all, there was togetherness. Even if the game never got finished, the effort to play it was its own reward.

The kitchen was more than a place to cook. It was where life pulsed. A parent stood over the stove, cooking from scratch without the aid of YouTube tutorials or meal delivery kits, while kids did homework at the table nearby, asking for help with a math problem or reading out loud from a social studies textbook. The radio might play in the background—Top 40 hits, or maybe just the news—while the smells of meatloaf, spaghetti, or casseroles filled the room. Dinner was rarely fancy, but it was home-cooked, reliable, and usually eaten together. There were no phone alerts buzzing, no tablets lighting up the table. You passed the salt. You talked about your day. You asked, “Can I be excused?” when you were done.

Household routines shaped the tempo of life. There were chores—mowing the lawn, vacuuming the carpet, raking leaves, setting the table, drying the dishes. Kids didn’t usually get out of them. In fact, they were seen as part of learning responsibility, as small ways of contributing to the family unit. Laundry days were all-day events, especially in homes without a dryer, where clotheslines stretched across backyards or basements. Saturday mornings were for cleaning, with parents blasting music—sometimes disco, sometimes classic rock—while everyone dusted, swept, and scrubbed. These weren’t moments anyone necessarily loved at the time, but they stitched the household together. They made the house feel like it belonged to everyone.

Holidays were particularly special in 1980s households, often infused with rituals that seem almost quaint today. Thanksgiving dinners were home-cooked marathons, with kids assigned to peel potatoes or set the “fancy” table. Christmas meant a real tree, carefully decorated with a mix of store-bought ornaments and construction-paper crafts from school. Birthdays involved homemade cakes, paper hats, and maybe a rented movie from the corner store. Celebrations didn’t need to go viral or be shared with hundreds of followers. They were for the people in the room, the ones who mattered most.

Without constant access to outside entertainment, families created their own. Parents read books to children at bedtime—dog-eared copies of “The Berenstain Bears,” “Little Golden Books,” or “Charlotte’s Web.” Siblings made up games in the backyard. Rainy days turned living rooms into forts made of couch cushions and blankets. The family photo album grew one Polaroid at a time. Film was precious. You didn’t take dozens of photos to find the perfect one. You took one, maybe two, and hoped someone wasn’t blinking. Then you waited days or weeks for the film to be developed. But when those prints came back, they were treasures—slightly faded, imperfect, and utterly real.

Home life wasn’t always idyllic. Like any time, families argued. Kids got grounded. Parents got tired. But those moments existed in real time and space, without the filter of a glowing screen or the escape hatch of the internet. You couldn’t retreat into a device. You had to work things out. That meant more conflict sometimes—but also more connection. The highs and lows played out in full view, and over time, they formed a kind of emotional blueprint—a shared understanding that this is who we are, this is how we live, and this is how we grow.

In the 1980s, the home was a world unto itself. The phone rang on the wall, tethered by a cord. You listened to music on the stereo, flipping the record or cassette over when it ended. You turned off lights when you left the room to save energy. You opened windows in the summer instead of cranking the AC. You had to get up to change the channel. You had to wait for your turn in the bathroom. The house functioned as a living, breathing system of cooperation and compromise.

Family time wasn’t manufactured or carved out—it simply happened because people were present. Not just physically, but mentally and emotionally. There was less noise. Fewer distractions. More space to talk, to listen, to be bored together. And in that boredom, creativity blossomed. Conversations stretched out. Stories were told. Inside jokes were born. That’s the kind of richness that’s hard to quantify, but impossible to forget.

The homes of the 1980s were filled with sound—of doors slamming, music playing, kids yelling from upstairs, pots clanging in the kitchen. They were full of light, both natural and fluorescent, and cluttered with objects that meant something: school papers on the fridge, mail on the counter, stacks of books by the couch, laundry in progress. They were alive. And in their imperfection, they were perfect.

Conclusion: Lessons from a Disconnected Time

The 1980s now seem impossibly far away—a world before texts and tweets, before Google and GPS, before we carried the internet in our pockets. It was a time when answers weren’t instant, when entertainment had to be sought out, and when people navigated their days without a digital lifeline tethered to their hands. And yet, looking back, that disconnected time wasn’t empty. It was full. Full of texture, of patience, of presence.

What stands out most about life in that decade isn’t what was missing—it’s what was present. People were where they were. Conversations happened face to face, not filtered through emojis or shortened to acronyms. If you wanted to know how someone was doing, you picked up the phone and asked—or you just showed up. Time moved slower because it had to. Plans were made and kept. You waited for things, and in that waiting, you developed an appreciation, a kind of emotional investment in whatever was coming next. There was an art to anticipation.

The absence of the internet didn’t mean the absence of connection—it meant connection was different. Less constant, but more deliberate. You didn’t comment on a photo to show you cared. You wrote a letter. You didn’t scroll past someone’s story—you sat across from them and listened. There was effort in every interaction, and that effort gave relationships a certain weight. You remembered birthdays because you made yourself remember, not because a platform reminded you. You looked people in the eye. You stayed in the moment.

And with all the so-called limitations of the time—the long lines, the missed calls, the need to rewind a tape before returning it—came a quiet resilience. People figured things out. You couldn’t look up a recipe in seconds; you called your mom or checked the index of a stained cookbook. If you got lost, you asked for directions. If you were bored, you had to invent something to do. Life demanded a little more from you, and in return, it gave you a stronger sense of agency.

That’s not to say the 1980s were perfect. They weren’t. Every era has its flaws, and the past should never be romanticized into fiction. But it is worth examining what we’ve lost in our sprint toward convenience and speed. The stillness of a Sunday afternoon spent reading a book. The weight of a phone call that you planned for and savored. The communal experience of watching the same show at the same time, and talking about it the next day. These were not extraordinary moments—but they were shared, and that made them meaningful.

In some ways, what made the 1980s special was the space it gave us—space to be bored, to be creative, to be with each other without being interrupted. In a world without constant notifications, you were allowed to lose track of time. You could go for a walk without tracking your steps. You could play outside until the streetlights came on, without anyone needing to check your location. You were trusted to figure it out. And you did.

The lessons from that time are not about rejecting technology or turning back the clock. They’re about remembering that human connection, attention, and presence are choices. That slowness can be a gift. That life doesn’t always need to be optimized to be worthwhile. Sometimes it just needs to be lived—as messily, beautifully, and un-digitally as possible.

We may never return to a fully disconnected world. But we can carry forward some of its values. We can choose to look up. To unplug. To gather. To wait. To wonder. Because in the end, the real legacy of the 1980s isn’t just the neon, the mixtapes, or the arcades. It’s the reminder that life—real life—happens not in the speed of a swipe, but in the depth of our attention.

Leave a comment