Introduction

The 1980s were an extraordinary time for photography—a vibrant era when the magic of capturing moments was deeply rooted in film, darkrooms, and tangible prints. This was long before smartphones and instant digital sharing; it was a world where every click of the shutter carried weight, and every roll of film held the promise of memories waiting to be developed. From the rise of consumer SLR cameras that put creativity into the hands of everyday people, to the iconic instant Polaroids that brought instant joy, photography in the ’80s was both a craft and a cultural phenomenon. In this blog, we’ll explore the fascinating landscape of ’80s photography—covering the technology, the culture, and the social vibe that made the decade’s images so unforgettable.

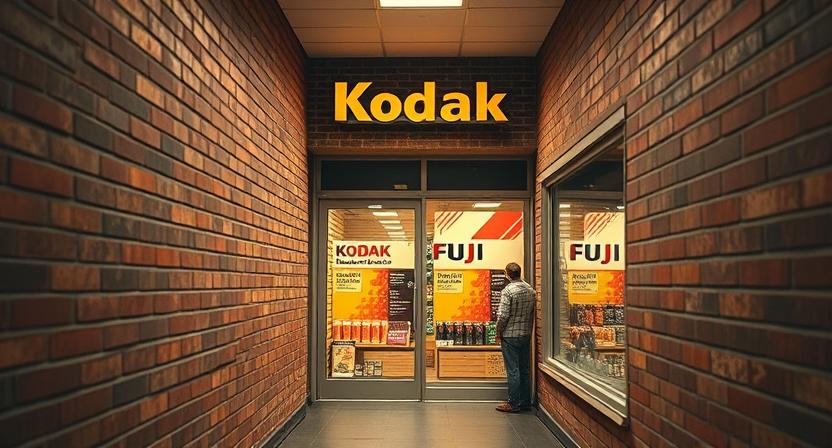

Whether you’re a photography enthusiast, a lover of ’80s nostalgia, or just curious about how people captured life before the digital age, this journey will take you through the cameras, films, and moments that defined a generation. We’ll dive into the battle between Kodak and Fuji, the DIY thrill of home darkrooms, and the earliest sparks of digital innovation, all while celebrating the unique styles and social scenes that surrounded photography in this iconic decade.

The State of Photography as the Decade Began

Picture this: It’s 1980, and photography isn’t at your fingertips like it is today. No smartphones, no instant previews, no Instagram filters. Instead, cameras are mostly film-based, clunky by today’s standards, and full of promise and mystery every time you load a roll of film.

At the start of the ’80s, photography was still a bit of a ritual. For many families, snapping a photo meant capturing a special moment — a birthday party, a vacation snapshot, or a holiday card photo. The camera wasn’t something you pulled out every minute, but rather a treasured gadget reserved for occasions worth remembering.

35mm film cameras were the workhorses of the era. These compact, mostly manual cameras had been popular for decades but saw a surge in accessibility during the ’80s. Brands like Canon, Nikon, Pentax, and Minolta were household names among photo enthusiasts and casual users alike. Using one required some know-how: loading film carefully, setting exposure and focus manually or semi-automatically, and, of course, waiting days to get prints back from the lab.

Then there were instant cameras, led by Polaroid, which burst into the scene like magic. Suddenly, you could press a button and hold a physical photo in your hand minutes later. Polaroids became the party cameras, the fun gadgets for kids and adults who loved the instant gratification of seeing their shot come to life before their eyes — even if the picture quality wasn’t perfect.

While professionals still used medium format and large format cameras for studio shoots and fine art, the 1980s were largely defined by this duality: the traditional 35mm film for planned, thoughtful shots, and the Polaroid for spontaneous, casual snapshots.

Photography was still tactile — you felt the weight of the camera in your hands, heard the satisfying click of the shutter, and smelled the faint chemical aroma when opening your photo envelope from the lab. Each roll of film had a limited number of exposures, so people were mindful about what they captured, making every shot count in a way that today’s endless digital clicking rarely matches.

In this era, photography was about patience, care, and a little bit of mystery. You never quite knew if your picture came out until the prints were developed, often days later. And that anticipation? It made those photos feel like treasures.

Consumer SLR Cameras: Bringing Creativity to the Masses

By the 1980s, photography was starting to open up in exciting ways—not just reserved for pros or hobbyists with deep pockets. One of the biggest game-changers was the rise of affordable consumer SLR cameras (that’s single-lens reflex for the uninitiated).

These cameras were like the Swiss Army knives of the photography world. Unlike simpler point-and-shoot models, SLRs gave users full control over focus, exposure, and shutter speed. That meant suddenly, people could start playing with things like depth of field, motion blur, and creative lighting effects without needing a photography degree.

Some of the most beloved models of the ’80s became iconic in their own right: the Canon AE-1, Nikon FE, Pentax K1000. The Canon AE-1, launched in the late ’70s but reigning through the ’80s, was revolutionary because it was one of the first cameras to offer automatic exposure modes at a price hobbyists could afford. It bridged the gap between full manual control and ease of use, making it the “gateway camera” for a whole generation of shutterbugs.

The Pentax K1000 was practically a rite of passage for photography students and casual users. Its rugged build and straightforward manual controls made it ideal for learning the craft from the ground up. And if you had one, you were instantly part of a community of people who loved the tactile, hands-on experience of photography.

SLRs transformed photography from mere snapshot-taking into an art form accessible to everyday people. Suddenly, you could experiment with everything from portraits to landscapes to street photography. The cameras encouraged patience and creativity — waiting for just the right moment, adjusting settings to get the perfect shot, and feeling that satisfying “click” when it all came together.

These cameras also fostered a culture of sharing and learning. Photography clubs, classes, and contests flourished as more people embraced the medium not just as a way to preserve memories but as a creative outlet.

And let’s not forget the romance of loading a roll of film, carefully winding it into the camera, and shooting 24 or 36 frames with thoughtful consideration—no endless scroll, just deliberate artistry.

In a way, consumer SLRs of the ’80s were the first step toward the modern photography culture we know today—tools that empowered users to express themselves visually long before digital filters and instant social sharing existed.

Instant Cameras and the Polaroid Phenomenon

If the 1980s had a photography mascot, it would almost certainly be the Polaroid instant camera—a colorful, boxy, and instantly recognizable device that brought a little bit of magic into homes, classrooms, and parties across the world. While traditional 35mm photography thrived on anticipation, Polaroids were all about the thrill of the now. They collapsed the waiting game, turning the act of taking a picture into an experience that unfolded right in front of your eyes.

Using a Polaroid was a ritual. You’d tear open a fresh film pack with a satisfying crinkle of foil, slide it into the camera’s belly, and hear the click of the door snapping shut. A small burst of excitement would rise as you lined up your shot—maybe crouching to get a better angle, or telling your friend to “hold still” while trying not to laugh. Then, with a firm press of the oversized shutter button, the camera would whirrr and eject a stiff, white-bordered rectangle into your waiting hand.

At first, the image was a milky, hazy blur. But within seconds, shadows would deepen, colors would bloom, and faces would sharpen into view. Watching a Polaroid develop felt a little like magic, and in a sense, it was—an alchemy of chemistry and light right there on the paper. This was photography you could see being born, not just later discovered after a trip to the photo lab.

The charm of Polaroids wasn’t just their speed—it was the spontaneity they encouraged. A Polaroid camera was perfect for those unplanned, often silly moments you didn’t want to lose. A messy kitchen after baking cookies, a late-night living room dance-off, or a quick goofy face made at the end of a long day—these weren’t staged portraits, they were life as it happened. Imperfection was part of the fun. A little overexposure? A thumb in the corner? Those quirks became the signature of the medium, making each shot feel alive and unique.

Polaroid cameras were also deeply social. In an age before smartphones, an instant print was a powerful connector. At a party, the camera would make the rounds, passed from person to person like a shared toy. People would crowd together for group shots, giggle while the film developed, and then swap prints like baseball cards. The physical act of handing someone a freshly made picture—still warm from the chemicals—was as much a gift as it was a photograph. Unlike today’s infinite duplications, each Polaroid print was one-of-a-kind.

The cultural reach of Polaroids went far beyond casual snapshots. Artists embraced them for their immediacy and unpredictability. Andy Warhol made the Polaroid part of his creative process, capturing friends, celebrities, and fleeting inspirations in instant form. Fashion designers and photographers used Polaroids as test shots before committing to full film shoots, relying on them to check composition and lighting. Even detectives, journalists, and scientists found them indispensable for quick, on-site documentation.

The design of the cameras themselves reflected the decade’s personality—playful, bold, and unmistakably ’80s. Models like the Polaroid OneStep and the Polaroid Sun 600 sported big, chunky bodies with oversized buttons, some in sleek black, others in bright rainbow-striped designs. Accessories like clip-on flash units and soft carry cases made them even more fun to own. In department stores, display shelves were filled with rows of these cameras alongside neatly stacked boxes of instant film, their packaging just as colorful and inviting as the prints they produced.

Polaroid marketing leaned into the idea that these cameras were for everyone. Commercials showed families snapping pictures on ski slopes, at barbecues, on beach vacations—anywhere joy happened. Taglines promised memories “you can hold in minutes,” and celebrity endorsements helped cement the Polaroid’s place in popular culture. By the mid-1980s, having a Polaroid at family events was nearly as common as having a birthday cake.

There was also a tactile, almost scrapbook-like culture around Polaroid prints. People would pin them to corkboards, stick them inside diaries, tape them to bedroom mirrors, or slide them under refrigerator magnets. Teenagers decorated lockers with Polaroids of friends, pets, and crushes. Couples would trade them like love notes. A wall of Polaroids in a home wasn’t just decoration—it was a timeline of laughter, milestones, and inside jokes.

Even the quirks of Polaroid film became part of its identity. The slight chemical smell, the occasional streaks or spots, and the signature white border all became instantly recognizable. Shaking the picture to “help it develop” (though unnecessary) became such a universal habit that it inspired songs and pop culture references.

By the late ’80s, competition from compact film cameras and emerging digital technologies began to challenge Polaroid’s dominance. Yet for much of the decade, the Polaroid was more than just a camera—it was a social glue, a creative tool, and a cultural icon. It turned photography into a shared event, something to be experienced together in real time.

Today, holding a vintage Polaroid from the 1980s is like holding a tiny time machine. The paper may have yellowed, the colors shifted, but the magic is still there. That little square frame captures not just the image of a moment, but the feeling of it—the laughter in the room, the warmth of the light, the joy of seeing something come alive right in your hands.

Film Development and the Home Darkroom Experience

There was a unique kind of magic in the air for anyone who set up a home darkroom during the 1980s. It was more than just a place to develop photos—it was a sacred, almost ritualistic space where patience, chemistry, and creativity met. Unlike the instant gratification of today’s digital displays, photography in this era demanded time, care, and a tactile connection to the entire process of turning exposed film into lasting memories.

Many photographers, especially the serious hobbyists and students, created their darkrooms in bathrooms, basements, or closets—anywhere they could control light. Bathrooms were popular because they had running water and could be sealed off from sunlight, which was crucial. Windows were often covered with thick blackout curtains or even foil to block every stray beam. Inside this carefully controlled darkness, the room would glow softly with a faint red or amber safelight, just enough illumination to see without spoiling the light-sensitive materials. It was a quiet, focused environment where every movement counted.

At the heart of the darkroom experience was the delicate dance between light and chemistry. The process began after finishing a roll of film, which itself was a suspenseful moment: you never knew exactly what you’d captured. Some sent their film off to professional labs, but many took pride in developing their own. Developing film meant working completely in the dark, using specialized tanks to immerse the film in a series of chemical baths. First, the film was soaked in a developer that revealed the latent image, then placed in a stop bath to halt development, followed by a fixer to make the image permanent and resistant to further light exposure. The final steps included washing off residual chemicals and drying the negatives. Each stage required precise timing and temperature control, because even a small error could ruin an entire roll.

Once the negatives were ready, the creative part of making prints began. Photographers would place a negative into an enlarger, a device that projected the tiny negative image onto a sheet of photographic paper. Under the comforting glow of the safelight, they carefully adjusted the focus, the distance of the enlarger head, and the exposure time to bring out the perfect balance of light and shadow. It was an art form in itself, with every adjustment influencing the mood and texture of the final print. The photographic paper, exposed for just the right amount of time, was then bathed in developer chemicals that slowly revealed the image. Watching the picture come to life, gradually appearing on the paper, was a moment of pure joy and anticipation.

The print didn’t stop there. After development, it was plunged into a stop bath to halt the chemical reaction, followed by a fixer to make the image permanent. Each print then needed a thorough wash in water to remove any remaining chemicals that could cause fading or damage over time. Finally, the prints were laid out on drying racks or hung on lines, waiting patiently to dry, sometimes under the gentle breeze of a fan or the warmth of a room heater. That waiting period often felt like the longest part, as photographers were eager to hold their creations and see the final result with their own eyes.

The darkroom wasn’t just a place for technical work; it was a sanctuary where photographers connected deeply with their craft. The slow, deliberate pace taught patience and mindfulness, a stark contrast to today’s instant everything. Many found the ritual meditative, a break from the rush of daily life. The occasional “happy accidents” — unexpected shadows, grain, or soft focus — became part of the charm, lending character and personality that digital perfection often lacks. There was pride in mastering the process, learning through trial and error how to manipulate light, timing, and chemicals to create the exact image envisioned.

This intimate knowledge of photography spread through clubs, classes, and word of mouth. Beginners learned not only how to operate cameras but also how to mix chemicals, set up enlargers, and handle fragile prints without ruining them. It was a hands-on, communal learning experience that brought people together, fostering friendships and healthy competition. The home darkroom was a place of creativity, experimentation, and shared enthusiasm.

However, the process wasn’t without its challenges. Maintaining the freshness of chemicals, avoiding dust or scratches on negatives, and ensuring a completely light-tight environment required vigilance and dedication. One small mistake—a minute light leak, a splash of water, a timing error—could destroy hours of work and valuable memories. Despite these hurdles, the satisfaction of holding a freshly developed print, knowing you had created it from start to finish, was unparalleled.

For those who preferred speed or convenience, the rise of one-hour photo labs in the ’80s offered a quick alternative. These labs became a fixture in drugstores and photo shops, promising prints back in about an hour. This service democratized photography further, making it accessible to those who didn’t want the hassle of chemicals and darkrooms. Yet, many purists and hobbyists regarded these labs as a compromise—quick but lacking the hands-on artistry and quality control of personal development.

Though digital photography would eventually render home darkrooms almost obsolete, the legacy of this era remains powerful. The lessons learned in those quiet, chemical-scented rooms about patience, craft, and the joy of creation have influenced generations of photographers. Today, a passionate group of analog enthusiasts keep the darkroom tradition alive, cherishing the tactile magic and creative control that defined photography in the 1980s—a golden era where every photo was a deliberate, cherished creation.

Flash Photography and Lighting in the 1980s

Lighting has always been the secret ingredient in photography — that magical element that can transform a simple snapshot into a striking, memorable image. In the 1980s, flash photography was undergoing exciting changes, making it more accessible and versatile for amateurs and professionals alike. But it wasn’t just about brightening a dark room; it was about mastering light to tell stories, create moods, and capture life’s fleeting moments with flair.

At the start of the decade, flash units were mostly bulky, external attachments that clicked onto the hot shoe of a camera or connected by a coiled cord. These flashes were powered by disposable batteries and used flash bulbs or xenon tubes to generate bursts of bright light. The technology wasn’t quite as refined as today’s digital flashes, but it gave photographers new creative possibilities beyond relying on natural or ambient light.

Many everyday photographers first encountered flash photography through on-camera flash units built into their point-and-shoot cameras or consumer SLRs. These built-in flashes often produced harsh, direct light that could flatten faces and cast unwanted shadows. But photographers who wanted better results invested in external flash units, which could be angled, bounced, or diffused to create softer, more natural lighting effects.

Bouncing the flash off ceilings or walls was a popular technique that became a hallmark of the era’s portrait and event photography. Instead of blasting subjects with a harsh, frontal light, bouncing allowed for more flattering illumination, creating a glow that wrapped gently around faces and reduced the starkness that direct flash produced. It wasn’t always easy to master — ceilings had to be low enough and walls the right color, and the photographer had to know how to position their flash unit just right — but the results were often worth the effort.

Studio photographers in the 1980s worked with an array of sophisticated lighting equipment: strobes, softboxes, umbrellas, and reflectors. These tools allowed professionals to sculpt light and shadow with precision, setting the mood and style for portraits, fashion shoots, and commercial work. The lighting setups could be elaborate and time-consuming, but they offered a playground for creativity. Some photographers experimented with colored gels over flashes, creating surreal or dramatic effects that became iconic of the decade’s bold visual style.

Another significant development during this time was the increasing use of TTL (Through The Lens) metering for flash exposure. This technology, which began gaining traction in mid-to-late ’80s cameras, allowed the camera to measure the light coming through the lens during a flash exposure, adjusting the flash output automatically for better exposure accuracy. For amateur photographers, TTL was a game changer — it removed much of the guesswork and helped avoid common flash pitfalls like overexposure or underexposure.

Flashbulbs, a relic from earlier decades, were becoming less common as electronic flashes took over. While flashbulbs created a bright, powerful burst of light, they were single-use and cumbersome, requiring replacement after each shot. Electronic flashes were reusable, faster to recharge, and more reliable, making them the clear choice by the mid-1980s.

Despite these advancements, flash photography still had its quirks. Harsh shadows, red-eye, and washed-out skin tones were frequent challenges that photographers had to navigate. Red-eye, caused by the flash reflecting off the subject’s retina, was especially common in casual snapshots. Photographers would often try different angles, use red-eye reduction features where available, or simply accept it as part of the era’s visual charm.

For many families, flashes became synonymous with holiday gatherings, school portraits, and birthday parties. The sudden burst of light was a cue that a moment was being immortalized. People learned to anticipate the flash’s pop, sometimes striking poses or making silly faces just before the camera clicked. That instant of frozen time, brightened by artificial light, created images that still evoke warm nostalgia today.

As the decade closed, electronic flash technology continued to improve, becoming smaller, more powerful, and more user-friendly. But the ’80s remain a special period where the challenge of mastering flash lighting added an extra layer of skill and artistry to photography. It was a time when learning to wield light well was a badge of honor for serious photographers, and a source of endless experimentation for anyone who loved to capture life’s bright moments.

Photography’s Place in Pop Culture and Media

The 1980s was a decade where photography transcended its role as merely a tool for capturing family moments or artistic expression — it became an essential part of pop culture, media, and the public consciousness. It was a time when images were not just frozen memories but powerful narratives that shaped how people saw the world and themselves. This was an era before smartphones and social media, so photographs in magazines, newspapers, album covers, and on television held tremendous sway. Photography was the visual language of the decade, telling stories of music, politics, sports, and celebrity in ways that words alone could not.

One of the most vivid ways photography infiltrated pop culture was through the rise of MTV, which launched in 1981 and forever changed how music and images intertwined. MTV made music videos a cultural phenomenon, but alongside the moving pictures, still photography thrived as a crucial part of the music industry’s visual storytelling. Album covers became iconic works of art in their own right, with photographers collaborating with musicians and stylists to create images that defined a band’s identity and era. Think of the striking portraits of Michael Jackson with his signature glove or Madonna’s rebellious fashion-forward shots that helped solidify her as a cultural icon. These photographs were plastered on posters in teen bedrooms, pasted on walls, and endlessly reproduced, making the visual persona of artists just as important as their sound.

Photography also played a vital role in shaping celebrity culture during the ’80s. The rise of celebrity magazines and paparazzi culture meant that images of stars were everywhere — on newsstands, in tabloids, and in glossy fashion spreads. Photographers like Herb Ritts and Annie Leibovitz became celebrities themselves, known for their ability to capture not just a likeness but the spirit of a subject. Their photographs combined glamour, intimacy, and storytelling, revealing facets of celebrities that fans hadn’t seen before. These images influenced fashion trends, social attitudes, and public perceptions, weaving a visual tapestry of the decade’s personalities.

But it wasn’t all about glamour. Photography was also a vital force in journalism, where photojournalists documented some of the most important and turbulent events of the 1980s. From the Cold War tensions to the fall of the Berlin Wall, from the devastation of famine in Ethiopia to the AIDS crisis, powerful images brought distant realities into the living rooms of ordinary people. Photographs by photojournalists like James Nachtwey and Mary Ellen Mark didn’t just report events; they evoked empathy and demanded attention. Their work pushed the boundaries of visual storytelling, using composition, timing, and emotion to capture moments that words could never fully express. These images shaped public opinion and sometimes even influenced policy, proving that a single photograph could hold immense power.

Sports photography also flourished during the ’80s, capturing the raw emotion of victory, defeat, and the human drama of athletic competition. Iconic images such as the triumphant fist pump of tennis star John McEnroe or the explosive power of a basketball dunk by Michael Jordan became part of the decade’s visual lexicon. These photographs were celebrated not just for their technical excellence but for the way they encapsulated the spirit of competition and the stories of perseverance that fans connected with deeply.

In the realm of fashion, photography was a creative force pushing boundaries and redefining beauty standards. Magazines like Vogue, Harper’s Bazaar, and Rolling Stone featured editorial spreads that combined art, fashion, and social commentary. Photographers experimented with lighting, color saturation, and composition to create images that were both visually striking and culturally resonant. The gritty urban aesthetics of street fashion photography mingled with the polished glamor of studio shoots, reflecting the eclectic, bold energy of the decade. This visual experimentation influenced not only fashion but also advertising, music, and film, making photography a key driver of ’80s style and identity.

Television news programs also relied heavily on photographic images to report the news, as still photos often complemented video footage or stood alone in print media. The immediacy of photographs gave news stories a face and a reality that words alone couldn’t provide. Iconic images like the Challenger Space Shuttle disaster or the miners’ strike in the UK became etched in the public memory, each photograph a stark reminder of moments of triumph and tragedy. The power of the photograph to capture history in a single frame elevated the role of photographers as chroniclers of their time.

Throughout the decade, photography in pop culture and media created a feedback loop — images influenced public perception, which in turn influenced the images produced. This interplay shaped everything from fashion trends to political discourse. Photographs became tools of persuasion, celebration, and sometimes protest. Whether in a glossy magazine, a gritty newsprint, or the glossy finish of a poster, photographs gave the 1980s its unmistakable visual identity.

In retrospect, the 1980s was a pivotal moment where photography’s place in pop culture and media solidified, bridging the analog past and the digital future. The decade’s iconic images continue to resonate today, reminding us of a time when photography was both a mirror and a lens — reflecting society’s hopes and fears while shaping how millions saw the world around them. The power of those photographs, taken with film and developed in darkrooms, remains undiminished, a testament to the artistry and cultural significance of photography in the 1980s.

Kodak, Fuji, and the Film Wars

The 1980s was not only a golden age for photography itself but also a fiercely competitive battleground for film manufacturers. At the center of this contest were two giants: Kodak, the American behemoth whose name had long been synonymous with family snapshots, and Fuji, the innovative Japanese company rapidly gaining ground with its cutting-edge technology and marketing savvy. This “film war” was about more than just sales; it reflected shifting global power dynamics, changing consumer habits, and the evolving demands of photographers around the world.

Kodak entered the decade with a commanding market position. For decades, it had been the undisputed leader in photographic film, dominating both consumer and professional markets. Its brand was so trusted that “Kodak moment” became a cultural catchphrase, synonymous with capturing life’s special occasions. Kodak’s products were familiar and widely available, from corner drugstores to big-box retailers. Families bought Kodak film rolls for their home cameras without a second thought, confident in the quality and ease of processing.

Yet, Kodak faced growing competition from Fuji, which was gaining traction thanks to its aggressive push into international markets and its reputation for innovation. Fuji’s film was praised for its sharpness, color vibrancy, and lower grain, appealing especially to amateur photographers and professionals seeking quality alternatives. Fuji didn’t just compete on product — it revolutionized marketing strategies, emphasizing the emotional and artistic aspects of photography in campaigns that resonated with younger generations. While Kodak often leaned on its heritage and reliability, Fuji presented itself as the forward-thinking challenger with a fresh vision.

Both companies made continual improvements in film speed and quality throughout the ’80s. Higher ISO films allowed photographers to shoot in lower light without sacrificing clarity or detail, opening new creative possibilities. These faster films were a boon for event photographers, photojournalists, and anyone eager to capture spontaneous moments without cumbersome lighting setups. The delicate balance between film grain and sensitivity became a key battleground, with Fuji and Kodak pushing their engineers to deliver sharper images at ever-increasing speeds.

Kodak also worked to diversify its offerings, introducing new formats such as the APS (Advanced Photo System) late in the decade, though it would be the ’90s before APS truly took off. Meanwhile, Fuji expanded beyond traditional 35mm film into instant films, slide films, and professional-grade products, striving to cover all bases for photographers at every level.

Brand loyalty during this period ran deep. Many families grew up trusting Kodak because it was the brand their parents used, a comforting continuity in an era of rapid technological change. Yet Fuji steadily chipped away at this loyalty, drawing customers with compelling innovations and appealing packaging. The battle spilled over into photo processing labs and stores, where the choice of film brand often determined which services and prints a customer would receive.

This fierce competition also drove price wars and product bundling, with manufacturers partnering with camera makers to offer film and camera kits, encouraging consumers to stick with one brand ecosystem. For photographers, these deals were sometimes confusing but often practical, ensuring they had compatible film and developing services to match their cameras.

At the same time, the competition spurred advancements in film chemistry and manufacturing techniques, leading to films that could better reproduce natural colors, enhance contrast, and withstand the rigors of varied shooting conditions. Photographers could experiment more boldly, knowing their film was capable of delivering consistent, high-quality results.

The “film wars” weren’t just about business; they reflected deeper cultural shifts. As Fuji expanded globally, it symbolized Japan’s rising technological and economic power, challenging American dominance in a key consumer market. For consumers, this competition translated into better products and more choices, fueling photography’s continued growth as a popular hobby and profession.

By the late 1980s, though digital photography was quietly emerging in laboratories, the war over film was still the front line of innovation and consumer attention. Kodak and Fuji’s rivalry encapsulated the excitement and challenges of a decade defined by rapid change and passionate dedication to capturing life’s moments on film.

Looking back, the battle between Kodak and Fuji helped shape the visual culture of the ’80s — a decade where every roll of film held the promise of a story, frozen in color and light, ready to be developed and cherished. The legacy of this competition still echoes in the way we think about photography today, reminding us of a time when film was king, and the brands behind it fought fiercely to earn their place in history.

Social Aspects: Photography Clubs, Classes, and Competitions

In the 1980s, photography was not just a solitary pursuit—it was a vibrant social hobby that brought people together in communities united by a shared passion for capturing images. Photography clubs sprang up in towns and cities across the globe, becoming welcoming spaces where amateurs and seasoned photographers alike could exchange ideas, learn new techniques, and share their work. These clubs were often hosted in community centers, libraries, or local schools, places where enthusiasts could gather after work or on weekends to dive deeper into their craft.

Joining a photography club was about more than just taking pictures—it was an opportunity to be part of a supportive community. Members would often organize group outings to scenic locations, museums, or urban landscapes, turning simple photo walks into social adventures. These excursions helped budding photographers practice new skills like composition, lighting, or using different types of cameras and films. The camaraderie formed during these outings often led to lifelong friendships, all bonded by the shared thrill of chasing the perfect shot.

Photography classes also flourished during this decade, reflecting the growing interest in the medium as both an art form and a practical skill. Community colleges, adult education programs, and specialized photography schools offered courses tailored to different levels of experience. Beginners could learn the basics of exposure, focus, and film development, while advanced students delved into topics like portrait lighting, darkroom techniques, and creative storytelling. These classes not only taught technical knowledge but also encouraged students to find their own unique photographic voice.

Competitions and exhibitions became important fixtures on the social photography calendar. Local newspapers and community organizations sponsored contests that invited photographers to submit their best work for public judging and recognition. These competitions fostered a sense of achievement and motivated participants to hone their craft. Winning a local contest or having one’s photo displayed in a public exhibition was a source of pride, sometimes launching amateur photographers into more serious pursuits or even professional careers.

The social aspect of photography also extended into print media. Photography magazines often featured readers’ submissions, letters, and tips, creating a two-way dialogue between publications and their audiences. This interaction nurtured a vibrant exchange of ideas and trends, further enriching the community spirit of the time. Some magazines even ran photo clubs or sponsored competitions, bridging the gap between casual enthusiasts and more dedicated hobbyists.

Moreover, photography served as a social equalizer in many ways. Regardless of age, profession, or background, anyone could pick up a camera and join these communities. The act of sharing images and techniques fostered inclusivity, helping people connect over a common creative interest despite other differences. For many, photography clubs and classes offered a refuge from the pressures of daily life—a space to express themselves and engage with others in meaningful ways.

The 1980s also saw the growth of specialty clubs focusing on niches such as black-and-white film, nature photography, or experimental techniques. These groups allowed photographers to dive deep into their interests and connect with like-minded peers. Through workshops, guest lectures, and portfolio reviews, members expanded their horizons and pushed the boundaries of their work.

All in all, the social culture of photography in the ’80s helped democratize the medium. It transformed photography from a personal hobby into a communal experience that enriched lives and broadened creative horizons. The friendships, skills, and confidence gained in these clubs and classes played a crucial role in the decade’s photographic renaissance, leaving a lasting legacy for future generations of image makers.

The Dawn of Digital: Early Innovations

The 1980s marked a fascinating and somewhat secretive turning point in the history of photography—a period when the first sparks of digital imaging began to glow, promising a future that would eventually transform the very essence of how we capture and share images. Yet, for most people at the time, digital photography was more a science-fiction curiosity than an everyday reality. The era was still firmly rooted in film, chemical processes, and analog cameras, but behind the scenes, engineers, scientists, and inventors were laying the groundwork for what would become one of the most revolutionary shifts in visual culture.

Unlike today’s instant gratification, the earliest digital cameras of the ’80s were cumbersome, expensive, and experimental. They were mostly confined to research labs and high-tech companies rather than consumer markets. These early prototypes aimed to capture images electronically, converting light into digital signals that could be stored, manipulated, and eventually displayed without the need for film or chemical development. This concept was groundbreaking but faced enormous technical hurdles. Image sensors were primitive, memory storage was limited and costly, and digital displays were still rudimentary. It was a time when capturing a single decent-quality digital image could take minutes, and the cameras themselves were bulky enough to be mistaken for scientific instruments rather than consumer gadgets.

Despite these challenges, several milestones in digital imaging technology occurred throughout the decade that hinted at what was to come. For instance, companies like Kodak—ironically the king of analog film—were experimenting with charge-coupled device (CCD) sensors and digital image capture. Kodak researchers developed prototypes that could capture low-resolution digital images, though these were far from practical consumer products. Similarly, Japanese electronics firms such as Sony and Canon dabbled in digital camera development, experimenting with early sensors and memory cards, sowing the seeds for later breakthroughs.

One of the most notable early digital cameras was the Fuji DS-1P, introduced in the late 1980s, which was primarily designed for industrial and professional use rather than everyday photography. It was a glimpse into the future but still out of reach for most consumers. The camera’s high price and technical limitations meant it never found widespread adoption, but its existence was a powerful signal that the digital revolution was brewing.

At the same time, the idea of digital photography stirred excitement and skepticism in the photography community. Enthusiasts and professionals who had spent years mastering film were understandably cautious about embracing a technology that, at the time, seemed clunky and inferior in image quality. The tactile satisfaction of loading film, hearing the click of a mechanical shutter, and developing prints in the darkroom was not something easily replaced by cold digital electronics. There was a genuine sense that digital could never replicate the artistry and nuance of film.

Yet, the promise of digital was tantalizing. It suggested a future where images could be reviewed instantly, edited effortlessly, and shared across electronic networks. This vision appealed particularly to photojournalists and commercial photographers who saw potential in faster workflows and new creative possibilities. The ’80s saw early discussions and experiments around digital image manipulation, setting the stage for the rise of tools like Photoshop in the following decade.

Meanwhile, the public’s experience of photography remained firmly analog. Film cameras continued to dominate sales, and photo processing labs thrived, fueled by the demand for prints from rolls of film. Most people could not imagine a world without film, and digital cameras were largely absent from the consumer landscape. The digital pioneers of the ’80s operated in a niche, laying the foundation but waiting for technology to catch up with their ambitions.

In many ways, the ’80s were a decade of coexistence and transition. While film photography was at its commercial and cultural peak, the seeds of digital photography were quietly planted in laboratories and corporate R&D departments. This period of experimentation was crucial—it allowed innovators to understand the challenges of digital capture, storage, and display, and to gradually improve sensor technology and data processing capabilities.

By the end of the decade, digital photography was no longer just a theoretical concept but a tangible, albeit expensive and specialized, reality. The groundwork laid during the ’80s would blossom in the 1990s and 2000s, eventually making digital photography accessible to the masses and fundamentally changing the way we create and consume images.

Looking back from today’s vantage point, the ’80s digital dawn appears as a time of curiosity, cautious optimism, and groundbreaking research. It was the moment when photography’s analog past met the digital future—a decade where innovators dared to imagine a new way of seeing the world, one pixel at a time. Though film ruled the day, the technological experiments of the ’80s set the stage for a revolution that would soon make photography more immediate, flexible, and democratic than ever before.

The Aesthetic and Stylistic Trends of ’80s Photography

The 1980s were a time of bold experimentation and vibrant creativity in photography, with visual styles reflecting the decade’s larger cultural and social energies. Photography didn’t just capture moments—it created moods and identities, often pushing the boundaries of what was considered conventional. Across genres, photographers embraced a range of aesthetics, from gritty street scenes to glossy fashion spreads, each style carrying its own cultural weight and artistic statement.

Street photography in the ’80s often conveyed a raw, unfiltered view of urban life. Photographers roamed city streets, capturing candid moments of everyday people, graffiti-covered walls, and the bustle of crowded neighborhoods. These images carried a grainy texture and high contrast that reflected both the toughness and vitality of the era’s urban environments. The decade’s social and economic tensions were evident in these photographs, revealing stories of struggle, resilience, and authenticity. Photographers like Bruce Davidson and Mary Ellen Mark became well-known for such gritty, humanistic work that highlighted marginalized communities and everyday life with empathy and urgency.

On the other end of the spectrum, fashion photography in the ’80s was a world of glamour and high energy. It was characterized by bold colors, dramatic lighting, and larger-than-life personalities. Fashion photographers worked closely with models, designers, and stylists to craft images that were as much about attitude as about clothing. The visual style was often polished and extravagant, incorporating neon hues, sharp contrasts, and playful compositions that echoed the decade’s love for excess and spectacle. Iconic photographers such as Herb Ritts and Helmut Newton created images that exuded sexiness, power, and sophistication, defining the visual culture of fashion magazines and advertising campaigns for years.

Portrait photography also evolved, blending traditional techniques with new stylistic flourishes. Glamorous studio portraits featured careful lighting setups to sculpt faces and create dramatic shadows, while environmental portraits placed subjects in meaningful settings that told stories about their personalities or professions. Many photographers played with color saturation and film stocks to achieve a distinctive ’80s look—often characterized by rich, punchy colors and a slightly soft focus that added a touch of warmth and nostalgia. The decade embraced both candid and posed portraits, capturing everything from celebrities to ordinary people with equal intensity.

The influence of pop culture and music was unmistakable across photographic styles. The vibrant aesthetics of music videos, album covers, and promotional shots seeped into broader photographic trends. Bright colors, graphic patterns, and a sense of theatricality permeated many images, reflecting the decade’s obsession with fame, identity, and self-expression. Photographers often drew inspiration from the flamboyant costumes, makeup, and sets of pop stars, blurring the line between photography and performance art.

Film grain, a hallmark of analog photography, became an artistic tool rather than a flaw in the ’80s. Photographers embraced grain for its texture and emotional impact, using it to add a sense of grit or nostalgia depending on the subject matter. Whether in black-and-white or color, grain contributed to the mood of images, making them feel more immediate and tactile. The choice of film stock was a crucial part of the stylistic palette, with some photographers opting for highly saturated slide films to achieve vivid colors, while others preferred softer, muted tones for a more introspective feel.

Composition in ’80s photography often broke traditional rules in favor of dynamic, eye-catching arrangements. Photographers experimented with angles, framing, and cropping to create tension and movement within the image. The use of off-center subjects, tight close-ups, and unconventional perspectives brought a fresh energy to photos, inviting viewers to engage more actively with the image. This playful approach reflected the decade’s broader spirit of innovation and its willingness to challenge norms.

Overall, the stylistic trends of the 1980s captured a decade defined by contrasts—between grit and glamor, tradition and innovation, personal expression and mass culture. Photography during this time was both a reflection of and a catalyst for these tensions, producing images that continue to inspire and define the era. Whether through the raw immediacy of street shots or the polished allure of fashion editorials, the aesthetics of ’80s photography remain a vivid testament to a decade of bold visual storytelling.

Conclusion

Looking back at photography in the 1980s, it’s clear that this was a decade of incredible transition, creativity, and community. The analog world of film and darkrooms fostered a tactile connection to the craft that many still cherish today. Whether it was snapping a candid Polaroid at a family gathering, joining a local photo club, or experimenting with the latest SLR camera, photography offered a way to freeze time and tell stories in a rapidly changing world. At the same time, the seeds of digital photography were quietly being planted, promising a future that would eventually revolutionize how we see and share images.

The ’80s remain a captivating chapter in photography’s story—one filled with vibrant aesthetics, passionate hobbyists, and fierce brand rivalries that pushed the art forward. By revisiting this era, we not only honor the tools and techniques that shaped a generation’s memories but also appreciate the timeless joy of capturing life’s moments, frame by frame.

Leave a comment