How the 1980s Made Nighttime Just Another Part of the Day

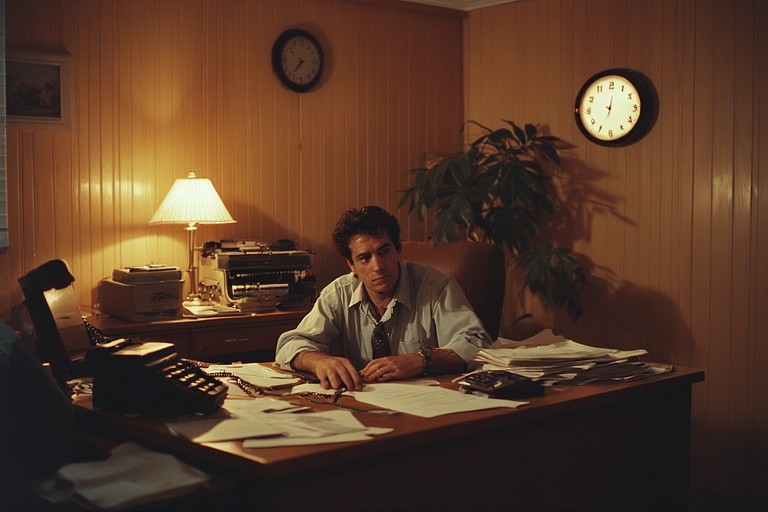

Introduction – When the World Slept

Before the 1980s, nights held a different kind of rhythm — a collective pause that most people accepted as natural. The sun’s setting signaled a gradual winding down of daily activities. Shops closed their doors by early evening, and banks locked up well before dinner. Television stations signed off after their final news bulletin, often ending with the national anthem or a test pattern, and left screens dark or flickering with static until morning. If you needed a loaf of bread or a late-night update on world events, you simply had to wait until the sun came up again. The night was not just dark; it was off-limits for most public life, commerce, and broadcast media. This nightly “off switch” created a clear division between day and night — a natural boundary around which society’s daily life was organized.

This quiet routine framed our experience of time and place. People planned their days around business hours and the television schedule, savoring the anticipation of the morning’s first news or the evening’s final broadcast. The night was, in a sense, a communal agreement to rest and disconnect. Yet, as the 1980s dawned, this agreement began to fray. Advances in technology, shifts in consumer behavior, and bold entrepreneurial experiments combined to crack open the night. What was once a time of darkness and rest was suddenly flooded with light, noise, and activity. This transformation was not instantaneous but it unfolded rapidly enough to change the fabric of everyday life.

The 1980s ushered in a world where the night lost its monopoly on silence and sleep. The stage was set for an era in which news cycles never ended, commercial messages filled the hours between midnight and dawn, and stores remained open when they once would have shuttered. As these changes unfolded, they reshaped our relationship with time, blurring the once-clear line between day and night, and creating a culture where being “always on” became the new normal.

News Around the Clock

In June 1980, media mogul Ted Turner launched Cable News Network, better known as CNN, the world’s first 24-hour television news channel. This was not merely a new channel but a radical reimagining of how news was consumed. Until then, television news was a packaged, time-limited product. Major networks offered concise broadcasts at fixed times, typically morning and evening, carefully curated summaries of the day’s most important stories. The idea that news should run nonstop was unprecedented and, at first, met with skepticism. Critics doubted there was enough to fill the hours and questioned whether viewers wanted to be bombarded by news at all times.

Yet Turner’s vision tapped into the pulse of a globalizing world. The truth was simple and powerful: while some parts of the world slept, others remained awake and events unfolded relentlessly across different time zones. CNN’s continuous feed offered viewers immediate access to developments anywhere, anytime. Whether it was a political coup in Africa, an earthquake in Asia, or a diplomatic crisis in Europe, CNN gave audiences a front-row seat, live and unedited. This real-time coverage forged a new relationship between viewers and news — one rooted in immediacy and the feeling of being connected to a larger global story.

The network’s defining moment came with the Gulf War in 1991, when it offered wall-to-wall coverage of military action unfolding live from Baghdad. Although this event technically fell just after the 1980s, the groundwork was laid throughout that decade. The Gulf War coverage demonstrated how 24-hour news could immerse viewers in events as they happened, turning distant conflicts into intimate, inescapable experiences. The CNN model shifted expectations forever: news was no longer something to catch up on during scheduled times, but a constant stream demanding real-time attention.

This relentless flow of updates transformed politics and public discourse. Citizens grew accustomed to being informed instantly, and leaders found themselves under continuous scrutiny. Yet the unceasing nature of 24-hour news also came with psychological consequences. The pressure to stay plugged in created a kind of collective anxiety, a fear of missing critical information. The day’s natural cycles of attention and rest gave way to an “always on” mentality, and the boundary between knowledge and overload began to blur.

Midnight Shopping: The Infomercial Era

As cable television expanded, the dead hours of the night became fertile ground for a new kind of programming — the infomercial. Before the 1980s, late-night TV simply signed off, leaving viewers with static or test patterns. But as channels multiplied and airtime needed filling, advertisers seized the opportunity to sell directly to viewers during these hours. The infomercial was born: a long-form advertisement that was part sales pitch, part entertainment, and often a little hypnotic.

Infomercials became a unique cultural phenomenon, blending charismatic hosts, flashy demonstrations, and persuasive calls to action. Products ranged from kitchen gadgets to exercise machines, often presented with a theatrical flair. The Ginsu Knife commercials, with their dramatic slicing of cans and tomatoes, became iconic symbols of this new format. Ron Popeil, a pioneer of the infomercial, used a folksy, reassuring style to sell everything from rotisserie ovens to spray-on hair. Tony Little’s high-energy fitness pitches turned the quiet hours into a high-octane sales event.

What made infomercials especially effective was their timing. At two or three in the morning, viewers were often alone, tired, and relaxed — conditions ripe for impulse buying. The hosts spoke directly to the viewer, often in an intimate tone that made the pitch feel personal. The “call now” urgency created a sense of immediacy, and payment plans lowered the barrier to purchase. Suddenly, shopping was no longer confined to store hours or even daylight. The night had become a marketplace.

These late-night sales pitches blurred the lines between entertainment and commerce, making the act of buying a kind of late-night ritual. The infomercial era planted early seeds of a consumer culture that expected products and services on demand, anytime, anywhere.

Lights On, All Night: The Rise of 24-Hour Stores

While the revolution unfolded on television screens, it also transformed the streets. Convenience stores like 7-Eleven pioneered the idea of being open all night, turning themselves into hubs of activity for night owls, shift workers, and late-night travelers. What began as a novelty — a place to grab coffee after midnight or a snack on a late drive — soon became a fixture of modern life.

The bright fluorescent lighting and open doors created a sense of safety and welcome that stood in stark contrast to the dark, quiet streets. For many, the 24-hour store became a dependable constant in an otherwise unpredictable night. It was a place to refuel, refresh, and connect, whether by chatting with a friendly cashier or simply sharing the company of other nighttime customers.

This shift coincided with the rise of the “third shift” economy — workers whose schedules required them to operate during nighttime hours. Nurses, factory workers, emergency responders, and others who worked through the night found in these stores a lifeline. The convenience store became more than a place to shop; it became a social and economic node in the nocturnal world.

The always-open model also changed eating habits and spending patterns. Fast food outlets, often located near convenience stores, began to stay open later or even 24 hours themselves. Late-night snacking and casual purchases became commonplace. The idea that shopping or grabbing a quick meal had to fit daytime schedules became outdated. Nighttime was no longer a pause but another phase of the daily cycle.

Machines That Never Slept

The 24-hour world was not just about lights and human activity; it was also about machines stepping in to fill the gaps. One of the most visible examples was the rise of Automated Teller Machines (ATMs). Previously, banking was confined to strict hours, but with the introduction and spread of ATMs, people could access cash and conduct basic transactions anytime, day or night. This new convenience redefined personal finance and reinforced the notion that services could be available on demand.

Alongside ATMs, vending machines became increasingly sophisticated. No longer limited to soda or candy bars, these machines began offering everything from hot coffee to sandwiches, enabling 24/7 snacking without the need for human staff. They dotted subway stations, office buildings, and convenience stores, feeding into the culture of immediate access.

The decade also saw early signs of home computing and bulletin board systems (BBS) that operated around the clock. Although the internet as we know it was still in its infancy, these technologies planted the idea of constant connectivity and access to information regardless of time. Nighttime became a prime period for computer enthusiasts and hobbyists to log on, explore, and communicate. This early digital culture foreshadowed the internet’s role in making 24-hour access the norm.

Together, these machines and technologies blurred the lines between day and night even further. The physical world of shops and banks was complemented by a growing digital ecosystem that never closed.

A Culture That Forgot How to Pause

With news outlets broadcasting nonstop, infomercials tempting viewers in the small hours, stores and machines offering round-the-clock access, the cultural meaning of night shifted dramatically. The once-sacred “nighttime pause” — a collective cessation of activity — began to dissolve. People were no longer forced to stop, to disconnect, or to rest. The boundaries between work, entertainment, consumption, and rest started to blur.

Shift workers formed their own communities, bound not by the traditional 9-to-5 schedule but by the rhythms of the night economy. For many, television became a companion during lonely hours, filling the silence with noise and images. The “off hours” shrank and eventually disappeared, replaced by a continuous cycle of activity.

This erosion of downtime had subtle effects on social norms and individual well-being. The natural distinction between day and night, activity and rest, work and leisure grew hazy. The psychological space that once allowed for reflection and rejuvenation gave way to constant stimulation. This new cultural reality set the stage for today’s “always-on” digital environment, where the pressure to be available and informed never truly ceases.

Pushback and Uneven Adoption

Despite the sweeping changes in cities and suburbs, not all communities embraced the 24-hour world at the same pace. Small towns, with their tighter-knit social fabric and slower rhythms, often resisted the shift toward constant activity. In many places, “closing time” remained a respected tradition, and stores retained their regular hours as a way to preserve community life and ensure rest for workers.

Cultural attitudes played a role as well. In some areas, the idea of round-the-clock shopping or nonstop broadcasting felt alien or even threatening to local values. People worried about noise, safety, and the erosion of shared downtime. These concerns sometimes sparked debates over zoning laws and business permits, illustrating the tension between progress and preservation.

Where the 24-hour model did take hold, it often adapted to local conditions. Some communities found compromises, such as staggered hours or limits on late-night noise, balancing economic benefits with social concerns. The uneven adoption of the 24-hour lifestyle showed that, while change was powerful and pervasive, it was never uniform or uncontested.

From Novelty to Normal

By the end of the 1980s, the idea of a world that slept in shifts rather than all at once was no longer an experiment but an established fact. The seeds planted by CNN’s bold news cycle, late-night infomercials, 24-hour convenience stores, and ever-awake machines had grown into a fully connected society. This new “always-on” mindset paved the way for the digital revolution of the 1990s and beyond.

What was once a novelty — watching news at midnight, buying a product in the small hours, or withdrawing cash at 2 a.m. — became everyday life. The 24-hour world transformed not only how people spent their nights but also how they understood time itself. The neat division between day and night gave way to a continuum of activity, expectation, and access.

This transformation brought undeniable benefits: convenience, immediacy, and a global connection that would have been unimaginable before. Yet, it also came with costs. The loss of quiet, the blurring of boundaries, and the rise of constant stimulation quietly reshaped how people rested, worked, and related to one another.

The dawn of the 24-hour world was a turning point. It redefined the rhythms of modern life, making the night no longer a place of darkness and pause but a vibrant stage for news, commerce, technology, and culture. As we live today in an era of smartphones, streaming, and instant communication, it is worth remembering that this always-on world had its origins in the daring experiments and cultural shifts of the 1980s — a time when the night first lost its monopoly on quiet.

Leave a comment