Introduction: From Cart to Click

There was a time when grocery shopping was as much a part of the rhythm of life as Sunday dinners or Friday night movies. In the 1980s, the weekly stock-up was a family affair or at least a carefully planned solo mission. It was not just about buying food—it was about preparing for the week ahead, making sure the household ran smoothly, and navigating the limited store hours that demanded planning rather than impulse. Grocery stores closed early, sometimes before dinner, and rarely opened on Sundays. That meant a forgotten gallon of milk was not something you could replace at 9 p.m. with the tap of a button.

Today, grocery shopping has morphed into something almost unrecognizable. The click of a phone screen replaces the sound of cart wheels clattering across tile. Services like Instacart, Amazon Fresh, Walmart+, and countless local delivery options promise to bring you everything from a carton of eggs to a gourmet cheese platter within hours—sometimes within minutes. The need to plan has been replaced by the ability to react in real-time. Dinner ideas can change on a whim because there’s no penalty for forgetting a key ingredient; someone else will fetch it for you.

This shift is not just about technology—it reflects deeper changes in the way we live, work, and even think about food. The 1980s model revolved around efficiency in a different sense: efficiency of a single big trip, efficiency of bulk storage, and efficiency of stretching ingredients to last until the next shopping day. The modern model prioritizes time saved in the moment, even if that means paying a premium for convenience. To understand how far we’ve come, and what we’ve lost along the way, we need to look closely at both worlds—one anchored in the steady rhythm of a weekly haul, the other dancing to the beat of instant gratification.

The 1980s Grocery Shopping Experience

In the 1980s, grocery shopping was a distinct event carved out from the weekend routine, often taking up a significant portion of Saturday morning or early afternoon. It wasn’t something squeezed in between other errands or done on a whim; it was planned, deliberate, and demanded focus. Before setting foot in the store, the preparation began at home with a handwritten shopping list. This list was far more than a casual reminder—it was the backbone of the entire operation. Usually penned in your mother’s neat cursive or your own hurried scrawl, it often appeared on the back of a scrap of paper: an old envelope, a torn corner of a notebook, or the reverse side of a phone message with the call time crossed out.

This list wasn’t optional. Leaving home without it was a risk—because the reality was clear: if you forgot something crucial, like bread or milk, you couldn’t just hop online and get it delivered an hour later. Grocery stores operated on limited hours, and many closed by early evening or shut entirely on Sundays. A missed ingredient meant improvising meals, borrowing from a neighbor, or making a special trip during the next available window, which was often inconvenient for working parents juggling family schedules. The list helped avoid those pitfalls by demanding you anticipate the week ahead—checking the pantry, noting down staples running low, and planning meals around what was needed.

Walking into a grocery store in the 1980s was stepping into a sensory world that is hard to replicate today. In the summer months, the blast of cold air conditioning hit you immediately upon entering, a sharp contrast to the heat outside. During colder seasons, the warm, yeasty aroma wafting from the bakery aisle could feel like a comforting invitation, drawing shoppers closer to the fresh bread and sweet pastries just pulled from the oven. The lighting was often fluorescent but softened by decorative touches—signs with bright red or yellow lettering announcing sales, or hand-painted chalkboards displaying the day’s specials.

The shopping carts themselves were a throwback compared to today’s lightweight models. Made from heavy metal, these carts rattled and clanked as you pushed them through aisles. Their front wheels were infamous for sticking or veering wildly, requiring a gentle but persistent tug to keep them straight. For kids tagging along, these carts could be mini adventures—riding in the basket or navigating narrow aisles alongside parents.

There were no self-checkouts, no contactless payments, and no scanning your own groceries on a smartphone app. Every purchase was ringed up by a cashier seated behind a classic checkout counter, expertly scanning barcodes with a mechanical beep. For many shoppers, these cashiers were familiar faces—seasoned workers who greeted you by name, remembered your usual purchases, and sometimes even offered small recommendations or friendly conversation. This human element made the checkout line more than a chore; it was a social touchpoint where brief but meaningful interactions occurred.

Grocery shopping in this era also doubled as a neighborhood social event. You might bump into your child’s teacher while reaching for a box of cereal, exchange a quick recipe tip with a neighbor by the pork chops, or overhear a conversation about a local school fundraiser near the produce section. These incidental connections gave the trip a community feel, a break from the anonymity that would become common in later decades.

Stores themselves were smaller than the sprawling supermarkets and supercenters of today, but this intimacy often made shopping feel more personal. The layout was straightforward and familiar, designed for efficiency and ease rather than overwhelming choice. The produce section was modest by modern standards—rows of bright, fresh staples like bananas, crisp apples, and navel oranges filled the bins. Exotic fruits were rare and treated as special treats; mangoes or kiwis might appear occasionally but were not a regular feature. Seasonal displays highlighted fruits and vegetables in their prime, reinforcing the connection between food and the calendar year.

The meat counter was often a highlight, with butchers working behind glass cases slicing cuts of beef, pork, or chicken to order. Meats were wrapped simply—white butcher paper or Styrofoam trays sealed with clear cellophane—and displayed plainly. Unlike today’s pre-packaged, heavily branded offerings, these meats felt fresher and more handcrafted, often sourced from local suppliers. If you had questions, the butcher was nearby, ready to offer advice on cooking or recommend the best cuts for stews, roasts, or grilling.

Shopping was about more than the items themselves; it was about relationships—between the customer and the store employees, between the shopper and the familiar brands, and even between the household and its routine needs. Because you made this trip once a week, every choice carried weight. You were mindful of how much to buy to avoid waste, how to balance cost with quality, and how to stretch ingredients into multiple meals. The pace was slower—less rush, less distraction—but the stakes felt higher.

In that slower pace, there was a quiet satisfaction: knowing your pantry was stocked, your fridge was full, and your family’s needs were met for the coming days. The 1980s grocery shopping experience was a mix of practicality, community, and sensory richness—a ritual that connected you to your food, your neighborhood, and your household in ways that the fast-paced convenience of today’s delivery model rarely can replicate.

Stocking Up for the Week

In the 1980s, the art of stocking up for the week was both a science and a deeply ingrained habit, shaped by the rhythms of family life, storage capabilities, and the natural limitations of grocery store hours. Unlike the spontaneous, often piecemeal shopping trips that have become common today, the weekly haul was a carefully choreographed event designed to ensure that the household ran smoothly until the next visit to the store. The shopping list was far from random—it followed a certain structure rooted in what could be realistically stored and what would endure the passage of days without spoiling.

Milk was a foundational purchase—usually bought by the gallon and carefully rationed to last the week. Bread came in loaves, often bought with the intention of slicing and freezing half to prolong freshness. Bread was rarely wasted; a forgotten loaf could mean stale sandwiches or breadcrumbs, but the freezer was a trusted ally. Cereal boxes were large and meant to feed the family for several mornings; favorites like Cheerios, Wheaties, or Raisin Bran were staples that carried a comforting familiarity to breakfast tables across America.

Canned goods held a place of honor on the pantry shelf. From green beans and corn to tomato soup and fruit cocktail, these cans were the backbone of quick, reliable meals. Their long shelf life made them ideal for stocking up and planning ahead. Potatoes were bought in sizable bags—often five pounds or more—because their versatility was unmatched. Mashed, baked, roasted, or fried, potatoes could stretch a meal in a way few other ingredients could. Frozen meat was another essential. Families often bought in bulk—a few pounds of ground beef, a whole chicken, or packaged cuts of pork or steak—all carefully labeled and stored in the freezer. This meat could be thawed as needed, offering flexibility and variety in meal planning.

For a typical family of four, the Saturday haul was both practical and plentiful. It might include five pounds of ground beef destined for everything from hamburgers to meatloaf, a whole chicken for roasting or stewing, a pound of American cheese for sandwiches or casseroles, a dozen eggs that would fuel breakfasts, baking, and snacks, and enough pasta—several boxes—to feed the family multiple times with different sauces and preparations. This kind of shopping was about foresight, ensuring there was no need to scramble for dinner ingredients midweek.

Seasonal availability played an important role in shaping menus and shopping lists. The grocery store’s produce section mirrored the natural growing seasons more than the year-round global supply chains of today. Spring brought the first tender strawberries, eagerly awaited and often reserved for desserts or snacks. Summer meant fresh sweet corn, its husks still green and silken, eaten fresh or frozen for later. Fall ushered in the arrival of crisp apples, pumpkins, and root vegetables, signaling a shift toward heartier meals and holiday preparations. Out-of-season fruits like berries or asparagus were either unavailable or priced steeply enough that they were treated as special treats rather than everyday staples.

Pantry staples were the unsung heroes of the 1980s kitchen. Bags of rice, jars of peanut butter, cans of tuna, and boxed macaroni and cheese were more than just convenient items—they were essential building blocks for the week’s meals. They were shelf-stable, affordable, and versatile, ready to transform into quick lunches, easy dinners, or emergency snacks. These staples were the reliable safety net that supported the more perishable items bought fresh.

Leftovers were never discarded thoughtlessly; they were part of a larger strategy to maximize resources and reduce waste. Sunday’s roast beef, slow-cooked to tender perfection, was rarely just a one-day meal. Slices would find new life on Monday in sandwiches for lunchboxes, then transform again into a hearty beef stew by Tuesday. Casseroles, soups, and stir-fries became vehicles for repurposing leftover vegetables and meats, making the most of every bite. This approach required intentional planning, often woven into the initial shopping list and meal prep for the week.

Another defining feature of 1980s grocery shopping was the strong sense of preparedness and self-reliance that permeated many households. It was common for families to own a chest freezer—usually tucked away in the basement, garage, or utility room—and keep it well stocked. These freezers were often packed with the results of bulk purchases, such as half a cow bought directly from a local farmer, wrapped and portioned into manageable packages. They might also contain frozen loaves of bread, homegrown or store-bought vegetables, homemade casseroles, and even baked goods.

This freezer stash served as a bulwark against unexpected challenges. If a snowstorm made roads impassable, a power outage forced a stay indoors, or an unexpected expense squeezed the family budget, that freezer stockpile meant meals could still be prepared without emergency trips to the store. This mindset—rooted in prudence, thrift, and a kind of quiet resilience—was a cornerstone of grocery shopping in the 1980s. It emphasized planning ahead, buying in bulk when possible, and being ready for whatever the week might bring.

This approach stands in stark contrast to today’s just-in-time shopping model, where smaller, more frequent purchases and rapid delivery services reduce the need for large storage spaces or extended meal planning. In the 1980s, the weekly stock-up was a form of insurance—a way to guarantee food security and household stability in an era before mobile apps and 24-hour supermarkets.

Tools of the Trade: Lists, Coupons, and Circulars

In the 1980s, grocery shopping was an exercise in preparation and strategy, relying on tangible tools that required care, attention, and a certain amount of ritual. Unlike today’s digital conveniences, where apps automatically track your lists and alert you to deals, the tools of the trade back then were simple, analog, and deeply embedded in everyday routines.

The grocery list was the most essential tool—a physical artifact that often began its life somewhere in the kitchen, penned in ink or pencil on a scrap of paper. It might be a torn piece of notebook paper, the back of a canceled check, or the reverse side of a kid’s homework sheet. It was a small but sacred document, carefully guarded to ensure it wasn’t left behind in the rush to leave the house. Losing that list was akin to losing your compass; it meant wandering aisles aimlessly or, worse, forgetting important ingredients that couldn’t be replaced until the next shopping day.

This list was rarely made in isolation. It was often shaped and reshaped by another critical tool—the weekly grocery circular. These circulars were colorful, fold-out pamphlets packed with glossy photos, bold typefaces, and enticing offers. They were delivered either tucked inside the Sunday newspaper or picked up in physical stacks near the store entrance. For many shoppers, the circular was a kind of weekly guidebook, signaling which items were on sale, what promotions were running, and which “loss leaders” were being used to draw shoppers in.

The concept of the loss leader was crucial: certain staple products would be sold at or below cost to attract shoppers, with the hope that they’d also pick up other items at full price. This tactic shaped meal plans more than you might realize. For example, a deep discount on chicken legs one week might lead to a menu dominated by roast chicken dinners, casseroles, and soups. A sale on canned tomatoes or pasta sauce could inspire an Italian-themed week. The circular didn’t just advertise products; it influenced how families ate, what recipes were tried, and how budgets were stretched.

Coupons, meanwhile, were an entirely different kind of shopping tool, but no less important. Couponing was serious business in many households, especially for families managing tight budgets or seeking to maximize value. Coupons came clipped from newspapers, magazines, or specialized coupon booklets, and were carefully organized—often stored in small envelopes, labeled folders, or accordion files designed to keep them neat and accessible. Some shoppers even developed their own systems for sorting coupons by category: dairy, canned goods, snacks, or household items.

The act of coupon clipping itself was a routine, sometimes a family affair. Mothers might sit at the kitchen table after the kids went to bed, scissors in hand, sorting through the Sunday paper and planning which coupons to bring along on the next shopping trip. The thrill came not just from saving a few cents but from matching coupons to sale items, scoring what was called a “double win.” Successfully pairing a coupon with a store discount meant paying a fraction of the usual price—an achievement that brought genuine satisfaction.

Cashiers played a pivotal role in this process. Unlike today’s mostly automated systems, coupons had to be checked manually at the checkout line. The cashier would carefully scan or visually verify each coupon, sometimes flipping it over to ensure it wasn’t expired or misused. Some stores added excitement to the bargain hunting by designating special “double coupon days,” when the value of coupons was doubled—turning a routine trip into a kind of game. On these days, savvy shoppers could be seen lining up early, armed with carefully prepared envelopes bursting with coupons, eager to maximize their savings. The atmosphere was often one of quiet camaraderie mixed with competitive spirit.

Behind these tools lay a deeper cultural and economic imperative: control. Managing the household budget was a serious responsibility, and every dollar saved mattered. In 1985, the average family of four might spend between $50 and $70 on a weekly grocery shop—a figure that, adjusted for inflation, would be roughly equivalent to $140 to $200 today. This wasn’t a trivial amount. Stretching those dollars required a constant balancing act between quality, quantity, and price. Every clipped coupon, every sale price carefully noted in the circular, and every item checked off the list was a step toward keeping the family fed without overspending.

The process of preparing for the store—assembling the list, clipping the coupons, studying the circular—was nearly as important as the shopping trip itself. It was a way for shoppers, often women in traditional households, to assert some measure of control over the unpredictable world of household finance. It was a ritual of care, discipline, and even pride. The effort put into preparation meant that when the family finally rolled through the sliding doors of the grocery store, they were armed not just with money but with knowledge, strategy, and a plan.

In this way, the tools of grocery shopping in the 1980s reflect a world in which time was spent up front to save money down the line, where patience was rewarded, and where the grocery trip was a purposeful endeavor shaped by the tangible artifacts of paper and scissors. The analog world of lists, coupons, and circulars stands in stark contrast to today’s digital, instant gratification-driven shopping environment, but it also reveals a deep-rooted human desire to prepare, save, and care for one’s family in a very hands-on way.

Grocery Stores of the 1980s

Stepping into a grocery store in the 1980s was to enter a familiar, almost comforting world that balanced the practical with the social. These stores were much more than just places to buy food—they were community hubs, landmarks in neighborhoods where faces were recognized and routines established. While the names on the storefronts might have changed depending on your region—Kroger dominated the Midwest, Safeway was a West Coast staple, Publix ruled the South, and A&P still clung to pockets of the Northeast—the layout and overall experience felt remarkably consistent across the country.

The physical size of these stores was modest by today’s standards. A typical 1980s supermarket measured somewhere between 25,000 to 35,000 square feet. This was large enough to stock the essentials but small enough to maintain a sense of intimacy and navigability. Unlike the sprawling mega-supermarkets and warehouse clubs that would emerge more prominently in later decades, these stores had a straightforward design. The produce section greeted customers near the entrance, offering seasonal fruits and vegetables arranged in neat wooden crates or simple wire baskets. The crisp scent of fresh lettuce, the bright colors of apples and oranges, and the occasional aroma of fresh herbs created an inviting atmosphere that made the chore of shopping feel a bit more pleasant.

Dairy products were usually placed along the back wall, requiring shoppers to traverse the aisles before reaching them. This layout encouraged a full tour of the store, maximizing exposure to various goods and increasing the chances that shoppers would pick up additional items. The meat department was a distinctive feature—often a chilled wall lined with butcher cases where cuts of beef, pork, and chicken were displayed under bright fluorescent lights. Unlike today’s pre-packaged supermarket meat aisles, much of the meat was cut and wrapped in-store by butchers who often became familiar faces to regular shoppers. These butchers took pride in their craft, offering advice on cuts, cooking tips, and sometimes even reserving prime steaks for loyal customers.

Aisles ran between these key sections like well-organized rows in a library, each dedicated to a specific category of dry goods: canned vegetables, boxed cereals, baking supplies, snacks, and household staples. The organization was deliberate and stable—shoppers rarely had to hunt for familiar products, as the layout rarely changed. It was a store you could navigate with your eyes closed after a few visits, creating a reassuring sense of routine in a rapidly changing world.

Product variety was narrower than what many shoppers expect today. While today’s grocery stores often feature extensive sections devoted to gluten-free, organic, international, and specialty foods, the 1980s stores focused primarily on basics. The ethnic foods section, if present at all, was often a single small shelf tucked near the spices or canned goods, featuring a limited selection of taco shells, soy sauce, a jar of curry powder, and perhaps a few other “exotic” ingredients. This was a reflection of the era’s food culture and immigration patterns; international cuisines had not yet permeated mainstream American grocery shopping in the way they would in later decades.

The emergence of warehouse clubs like Costco and Sam’s Club in the mid-1980s began to alter the grocery landscape, but their impact was gradual and somewhat specialized. These new giants introduced the concept of buying in bulk at rock-bottom prices—an idea that seemed revolutionary to many shoppers accustomed to the weekly stock-up trip. Suddenly, you could purchase a gallon jug of mayonnaise, a 25-pound sack of rice, or an enormous pack of paper towels for much less per unit than the smaller packages in traditional stores. However, these warehouse clubs were not part of the average family’s weekly routine. Rather, they were destinations for special trips—planned excursions where families or savvy shoppers loaded up freezers and pantries for months ahead. This was a mindset shift: warehouse clubs required a car with ample trunk space and a long-term storage plan, neither of which fit into the quick Saturday morning shop.

For the majority, neighborhood grocery stores remained the heart of weekly shopping. These stores fostered a personal connection with customers. Cashiers and clerks often knew their shoppers by name and might even set aside items they knew were favorites—like the last loaf of freshly baked rye bread or a special brand of coffee. This personalized service created a sense of community and loyalty. It wasn’t unusual for a shopper to stop for a brief chat with the butcher or produce clerk, exchanging recommendations or news about local events. These stores, in a way, anchored families within their communities, weaving grocery shopping into the fabric of daily life.

Another hallmark of the 1980s grocery store was its predictability. Unlike the modern supermarket, where product lines, layouts, and brands frequently change in response to trends or corporate decisions, the stores of the 1980s adhered to a steady, reliable routine. Shoppers rarely needed to learn new locations for their staples. The dairy case was always at the back, the frozen food aisle typically near the meat department, and the checkout lanes near the front. This consistency made shopping less stressful, especially for those who shopped with children or on tight schedules.

The store’s environment also reflected the technology of the era. Scanners were just beginning to appear in some places, but many transactions still relied on manual price checks and handwritten tallying. Background music was often a mix of Top 40 hits or easy listening tunes, creating a familiar soundtrack to the shopping experience. Fluorescent lighting bathed the store in a steady glow, and the occasional fluorescent sign advertising a sale or special deal punctuated the aisles.

In essence, grocery stores in the 1980s combined function with familiarity, creating spaces that felt safe, known, and welcoming. They were more than mere retail environments; they were places where the rhythm of family life was reflected and supported, where a weekly trip to stock the pantry was as much about tradition as it was about necessity. This steady, unchanging presence provided a kind of comfort in a decade defined by social and economic shifts.

Technology of the Time

Stepping into a grocery store in the 1980s was like entering a world that balanced the emerging promises of technology with the comforting familiarity of hands-on routines. Unlike today’s sleek, ultra-modern supermarkets with gleaming scanners and digital displays at every turn, the technology of the 1980s grocery store was far more tactile, mechanical, and often visibly imperfect.

The first thing you’d notice was the absence of uniform, instantaneous pricing technology. Instead, nearly every product bore a small paper price sticker—sometimes applied long before it reached the shelves, sometimes affixed by store employees just days or even hours before you shopped. These stickers were the lifeblood of pricing, and their neat application was a quiet but vital part of the store’s behind-the-scenes rhythm. Clerks wielded handheld pricing guns, which released a fresh sticker with a satisfying click and adhesive backing, replacing outdated or incorrect prices. This physical, manual process meant that pricing errors could easily occur if a sticker was misplaced or forgotten altogether.

At the checkout counter, the pace was set by the rhythm of a cashier’s fingers on a mechanical register. Instead of scanning dozens of items in seconds, cashiers typed in each price manually—a task that demanded concentration and speed. Accuracy was crucial; a slip of a finger could mean having to stop and call over a supervisor or a price checker, causing an awkward pause as the line behind you grew longer. Customers accepted these slowdowns with a degree of patience, understanding that this was just part of the shopping ritual. The register itself was a bulky machine, often with large buttons and a mechanical drawer that popped open with a satisfying clunk to reveal cash and coins.

The Universal Product Code (UPC) barcode system was beginning to change this process, but it was still in its infancy in many stores. Though UPC barcodes had been invented in the early 1970s, their widespread adoption took time. By the mid-to-late 1980s, more stores began installing laser scanners, but the technology was still a novelty for many shoppers. It was not uncommon to hear whispers of amazement or see eyes widen when a cashier passed a can of soup or a box of cereal under the red laser light, instantly revealing the price on the register screen. For many, it was the first glimpse of a high-tech future where computers could speed up everyday tasks.

Despite these early advancements, the grocery shopping experience remained largely manual when it came to deals and discounts. There were no digital loyalty cards or automatic price matching systems. Sale prices were communicated through brightly colored signs or flyers, but it was entirely up to the shopper to notice and remember them. When you reached the checkout, the cashier had no way to automatically apply discounts—you had to rely on your own memory or hope the cashier was paying attention. If the sign said “Cereal $1.99,” it was your responsibility to ensure that was the price rung up. The absence of automated pricing meant that errors sometimes worked in favor of the store and sometimes in favor of the customer, adding an unpredictable element to each transaction.

Payments were equally analog by modern standards. Cash was the most common form of payment, and coins jingled in purses and pockets as people counted out bills for their groceries. Checks were also widely accepted, though they added complexity to the transaction. When paying by check, customers were typically required to show photo identification to prevent fraud. The process involved the cashier imprinting the credit or debit card onto a piece of carbon paper using a mechanical device called a “knuckle buster.” This device pressed the raised numbers on the card onto the paper, creating a physical record for the store. It was a slow, manual process, very different from today’s instant electronic authorizations.

Credit card payments were just becoming more common, but the technology had not yet caught up to today’s seamless experience. There were no magnetic stripe readers as we know them now, no chip-and-PIN systems, no tap-to-pay contactless options, and certainly no smartphone wallets or digital currencies. The credit card transaction was a tangible exchange involving physical imprinting and handwritten receipts. In busy stores, this could slow down the checkout line significantly, sometimes leading to visible impatience or sighs from customers waiting behind.

This absence of technology-driven speed and automation meant the entire checkout process was a slower, more deliberate ritual. Shoppers didn’t expect rapid-fire efficiency but rather a complete, careful transaction. The time spent at the register was often a moment to catch your breath after weaving through crowded aisles and a chance for a brief exchange with the cashier. It was not uncommon for customers to chat briefly, ask about new products, or exchange pleasantries during the wait. The technology—or lack thereof—did not make shopping easier in the way it does today, but it did create a distinct rhythm, a human-paced cadence that shaped the entire grocery experience.

In this way, the technology of the 1980s grocery store felt like a bridge between eras: an era of manual, human-centered commerce just beginning to meet the possibilities of digital automation. It was a time when every price was tangible, every transaction deliberate, and the rhythm of shopping was slower but deeply familiar—a far cry from the instantaneous convenience we take for granted today.

Today’s Grocery Landscape

Fast-forward to the 2020s, and the world of grocery shopping has transformed into a sprawling, almost overwhelming sensory and technological experience. The modern supermarket is not just a place to buy food—it is a curated marketplace designed to cater to every conceivable taste, dietary preference, and lifestyle choice, sprawling over 50,000 to 70,000 square feet in many cases. These vast spaces can feel more like small shopping malls than the humble neighborhood grocers of decades past.

What strikes visitors immediately is the explosion of choice. No longer confined to a few brands and basic staples, the aisles are filled with an incredible variety of products, often arranged to entice and inspire. For example, the once-modest dairy section now features a dizzying array of milk alternatives: almond, oat, cashew, hemp, pea protein, and coconut milk all jostle for shelf space alongside traditional cow’s milk. Similarly, yogurt has evolved far beyond the plain tubs of the past to include Greek strained yogurts, Icelandic skyr, drinkable kefir, and a growing selection of plant-based options made from coconut or soy, catering to everything from gut health to indulgent dessert cravings.

The produce section, too, tells a story of global interconnectedness and consumer demand. Exotic fruits like avocados, pineapples, and mangos, which were once considered seasonal or luxury items, are now ubiquitous year-round, shipped fresh from farms across the globe with astonishing speed. The fresh herb and salad bar sections offer microgreens, edible flowers, and a myriad of greens like kale and arugula that barely registered in the 1980s. Organic produce has moved from niche specialty to mainstream necessity for many shoppers, with clearly marked sections or even entire aisles dedicated to certified organic fruits, vegetables, and packaged goods.

Beyond the fresh foods, specialty diets have carved out their own shelves and aisles. Gluten-free products, once scarce and expensive, are now widely available and competitively priced, offering everything from breads and pastas to snacks and baking mixes. Vegan and plant-based meat alternatives—made from soy, pea protein, or even lab-grown ingredients—are no longer curiosities but featured items, sometimes with their own branded sections. International foods have exploded in diversity; aisles once dedicated to “ethnic foods” now carry ingredients and prepared meals from every corner of the world, reflecting the multicultural makeup of modern cities and a curiosity about global cuisines.

Budget chains, which used to be synonymous with limited choices and bland offerings, have reinvented themselves with higher-quality, fresh, and even prepared foods. It’s not unusual to find sushi counters, freshly prepared salads, pre-marinated meats ready for the grill, and a wide array of organic and “natural” products in stores like Aldi or Lidl, once known for their strict focus on cost-cutting. This democratization of specialty products has blurred the lines between traditional grocery stores and high-end specialty markets.

Technology shapes every inch of the contemporary grocery experience. Digital shelf labels flicker quietly on the edges of shelves, updating prices and promotions instantly without a single paper tag in sight. Shoppers armed with smartphones can scan QR codes to access detailed product information, recipes, or even video tutorials. Self-checkout lanes, once rare novelties, now crowd the front of the store, reducing wait times for smaller purchases and appealing to shoppers eager to control their own speed through the store. Some stores have even embraced cashierless technology, where customers simply scan their phones at entry, grab their items, and leave while the store’s cameras and sensors handle the billing.

Store loyalty programs have evolved into sophisticated data-gathering tools that tailor discounts and product recommendations directly to individual customers. Before you even step inside, your favorite store’s app might ping you with a coupon for your preferred brand of coffee or a reminder that your favorite snack is on sale this week. Personalized promotions often influence what shoppers pick up, nudging them toward products they might not have considered. While convenient, this data-driven personalization has also sparked conversations about privacy and consumer autonomy, as every purchase becomes part of a vast web of information.

The modern store is also a place of experience and entertainment. Many chains have added in-store cafes, cooking demonstration areas, and tasting stations that invite shoppers to try new products before buying. The sensory experience is carefully crafted, with ambient music, strategic lighting, and thoughtfully arranged displays designed to make shoppers linger, explore, and indulge. Where the 1980s store felt utilitarian, today’s market blends utility with lifestyle, making grocery shopping as much about discovery and delight as it is about replenishing the pantry.

In essence, today’s grocery landscape is a sprawling, complex ecosystem built on diversity, choice, and technology, reflecting the vast changes in society’s tastes, values, and habits. The grocery store is no longer a simple place to stock the fridge; it is a destination shaped by global supply chains, consumer data, and an ever-growing array of products designed to fit every lifestyle imaginable.

The Rise of On-Demand Grocery Delivery

The transformation of grocery shopping took a seismic leap in the early 2010s when the concept of on-demand grocery delivery began to move from a futuristic novelty into an everyday convenience. What once felt like an indulgence reserved for busy executives or tech enthusiasts has now become a staple service embraced by millions across urban, suburban, and even some rural areas. Services like Instacart, Shipt, Amazon Fresh, Walmart+, and a host of local grocery chains have woven themselves into the fabric of modern life, promising not just groceries but instant access to a well-stocked pantry without ever leaving the couch.

This evolution reflects a profound shift in how people interact with food procurement. The rigid schedules of the past—where a careful weekly plan and a Saturday morning stock-up were essential—have given way to a world where immediacy reigns supreme. In metropolitan hubs like New York, San Francisco, and Chicago, ultrafast delivery startups compete to fulfill orders in under 30 minutes. The ability to summon fresh bread, eggs, or that elusive bottle of craft hot sauce with a few taps on a smartphone has created a new rhythm of consumption defined by flexibility and spontaneity.

The convenience of on-demand delivery is not just about saving physical time or skipping the parking lot battles. It’s about removing mental barriers and the stress of planning. Forgetting a critical ingredient no longer disrupts the evening meal plan; missing a household staple is no longer an inconvenience but a minor blip instantly corrected. This immediacy has reshaped consumer expectations and behaviors. Many households no longer feel compelled to buy in bulk or stockpile perishables in the freezer because replenishment is just a quick order away. Meal planning is less about projecting an entire week and more about improvisation, creativity, and responding to hunger or cravings in real-time.

Behind this seemingly effortless service lies a complex web of logistics, technology, and human effort. Delivery platforms employ sophisticated algorithms that balance shopper availability, store inventory, traffic conditions, and delivery routes to optimize efficiency. The customer’s seamless experience masks the pressure cooker environment faced by gig workers, who often race through crowded aisles, carefully select produce to match customer preferences, and rush deliveries through unpredictable city streets. These shoppers operate under strict time constraints, with accuracy and speed paramount, yet their work is often undervalued and precariously compensated.

Financially, on-demand grocery delivery carries a premium that is easy to overlook amid the allure of convenience. Delivery fees, service charges, and mandatory tips can quickly add 15 to 25 percent or more to the cost of a typical grocery run. Additionally, prices on items purchased through delivery apps are frequently marked up compared to in-store pricing. These hidden costs are the trade-off consumers accept for instant gratification and the luxury of bypassing traditional shopping challenges like crowds, parking, and carrying heavy bags.

The environmental impact is another dimension often hidden from view. Increased packaging for individual orders, repeated delivery trips, and reliance on gig economy vehicles contribute to a larger carbon footprint than a single consolidated weekly shopping trip. Some companies are actively working to mitigate these effects by introducing reusable bags, optimizing delivery routes, and even piloting electric vehicle fleets, but the overall footprint remains a growing concern.

Culturally, the rise of on-demand grocery delivery marks a significant departure from earlier shopping rituals. The social interactions, the spontaneous conversations with store clerks, and the familiar ritual of wandering aisles are largely replaced by digital transactions and doorstep drop-offs. For many, this loss of communal connection is a small price to pay for efficiency, but it nonetheless signals a redefinition of what it means to shop for food. The delivery model also reshapes family dynamics—where once the weekly grocery trip might be a shared outing or a teaching moment for children, now the chore can be delegated entirely to an app and a stranger, freeing time but eroding that lived experience.

Ultimately, on-demand grocery delivery epitomizes a broader societal embrace of immediacy and convenience that defines the 21st century. It simultaneously offers incredible flexibility and ease while introducing new complexities around cost, labor, and sustainability. Understanding this service’s profound impact requires appreciating not just the technology and consumer benefits but also the human and systemic trade-offs that come with shopping at the speed of a click.

Shopping Frequency: Weekly vs. Multiple Times a Week

In the 1980s, grocery shopping was a well-established ritual centered around a major weekly trip, typically scheduled on a Saturday or Sunday morning. This once-a-week expedition was more than just a matter of convenience; it was woven into the very fabric of family life and the practical realities of the time. Stores had limited hours—often closing by early evening and sometimes shutting their doors entirely on Sundays—so multiple trips per week were neither necessary nor particularly feasible. With fewer cars per household and less traffic congestion than today, a trip to the grocery store was often a deliberate, planned event, requiring a careful checklist and some advance preparation.

Transportation limitations also played a key role. Many families relied on a single car, making it more efficient to maximize what could be carried and stored in one go. The containers and packaging of the day were not always designed for long shelf life or easy storage—milk came in half-gallon or gallon glass bottles that couldn’t be stashed away in a freezer, and many fresh foods lacked the preservatives or vacuum-sealing technology available today. This encouraged buying enough to last a week but not much more, with the knowledge that perishables had to be consumed relatively quickly.

Culturally, this weekly shopping pattern also reinforced a mindset of planning and economy. Meal plans were crafted to use ingredients efficiently and avoid last-minute trips. For many families, the weekly grocery haul dictated what was served for dinner throughout the coming days, with leftovers carefully managed and repurposed to extend the value of the purchase. The grocery list was sacred—a roadmap to ensuring the household ran smoothly, avoiding the need for midweek scrambles.

Fast forward to the 2020s, and this picture looks fundamentally different. The notion of limiting oneself to a single, large shopping trip now feels restrictive or even outdated to many consumers. Technological advances and changing lifestyles have ushered in a more dynamic shopping frequency. While some people still embrace the bulk-buying, stockpiling model reminiscent of the 1980s, many others have shifted to multiple smaller shopping trips spread throughout the week—or, increasingly, no in-person trips at all, opting instead for frequent deliveries tailored to immediate needs.

This shift reflects broader changes in modern life. With more dual-income households, busier schedules, and a culture that values instant gratification, waiting seven days for a grocery restock can seem inefficient. Instead, shoppers now build their menus around what they feel like eating at the moment, confident that if they change their minds, missing ingredients can be ordered with minimal hassle and delivered rapidly. The convenience of digital shopping apps and on-demand delivery services means consumers can fill gaps in their pantry in real-time, rather than basing meal plans strictly on what’s already in the fridge.

Another consequence of this change in shopping frequency is its impact on food waste. The scarcity mindset of the 1980s—born out of limited store hours and less frequent trips—naturally encouraged careful use of every ingredient. Households learned to stretch groceries, creatively repurpose leftovers, and plan meals to avoid spoilage. In contrast, today’s abundance and easy replenishment can paradoxically lead to more food waste. When replacement items are just a tap away, shoppers may buy more than they can consume before it spoils, or let older groceries languish behind fresher products, forgetting about the food tucked away in the back of the fridge or freezer.

The cost of this waste, while significant environmentally and economically, often feels less immediate or visible because the effort to correct it is minimal. If a carton of milk expires unused, it’s easier to chalk it up as a minor loss rather than a failure in planning, because you can reorder a fresh one quickly without leaving home. This change reflects a larger shift in values—where convenience and choice sometimes outweigh considerations of thrift and sustainability.

In sum, the shift from a weekly stock-up to a fluid, on-demand shopping model illustrates how changes in technology, culture, and lifestyle have transformed not just when and how we buy groceries, but also how we think about food, consumption, and waste. The once-predictable cadence of a Saturday morning grocery run has been replaced by a more fragmented, instantaneous cycle, reshaping our relationship with the kitchen and the food we eat.

Price Comparisons and Economic Factors

Comparing grocery prices between the 1980s and today is a complex endeavor that goes far beyond simply adjusting numbers for inflation. While the sticker price of items then and now offers one glimpse, it’s the broader economic context, evolving consumer habits, and product diversity that reveal the true story of how grocery spending has changed over the decades.

Take milk, for example. In 1985, a gallon of whole milk cost roughly $2.20. Today, the average price hovers closer to $4.50 to $5.00 in many parts of the country. Bread, a staple on every 1980s grocery list, could be bought for just 55 cents a loaf back then, while a dozen eggs might have set you back about 80 cents. At those rates, a family of four could fill a cart with a week’s worth of essentials for $50 to $70, which when adjusted for inflation translates roughly to $140–$200 in 2025 dollars. Yet, many modern families routinely spend well beyond that amount for comparable groceries.

Why the discrepancy? Inflation certainly plays a role, but it’s only part of the picture. The range of choices available today vastly outstrips what was on shelves in the 1980s. Take orange juice, a common item then and now. In the 80s, you bought a single kind of orange juice—usually frozen concentrate or a carton of reconstituted juice. Now, supermarket shelves are lined with options: fresh-squeezed varieties, cold-pressed blends, organic labels, calcium- and vitamin-fortified brands, no-pulp versions, and even plant-based “juice” alternatives like carrot-ginger or turmeric blends. Each of these premium or niche products carries a higher price point, reflecting not just production costs but also targeted marketing to health-conscious or trend-driven consumers.

Beyond the product variety, packaging and branding also inflate prices. Whereas many products in the 1980s came in simple cardboard boxes or glass bottles with minimal graphics, today’s grocery items often come in brightly colored, heavily branded packaging designed to catch the eye and command a premium. Convenience features—resealable bags, single-serve portions, eco-friendly materials—also add to costs. What was once a basic bag of rice is now available in portioned pouches with organic or non-GMO labels, sometimes doubling or tripling the price.

Bulk buying was a cornerstone of 1980s grocery economics, and it helped families keep costs low. Purchasing family-sized packs of meat, five-pound bags of rice, or cases of canned goods meant stretching the budget further and reducing trips to the store. Refrigeration and freezing technology were improving but still limited, so this strategy balanced quantity with the need to consume food before spoilage. Warehouse clubs like Costco were emerging but hadn’t yet fully transformed shopping habits.

In contrast, the rise of on-demand shopping and delivery in the 2020s often encourages smaller, more frequent purchases. While this provides flexibility, it typically comes with a higher per-unit price. Single cans, pre-portioned meats, and specialty items can cost more than their bulk counterparts, even before delivery fees and service charges are tacked on. Additionally, these platforms sometimes charge “convenience pricing,” where items cost more than in-store equivalents, reflecting the operational expenses of picking and delivering orders.

Economic factors also include wage trends and household income changes. Although median wages have risen since the 1980s, the increase hasn’t always kept pace with the rising cost of living or the diversified expectations of consumers for quality, convenience, and specialty products. Food inflation specifically can outpace general inflation, driven by factors such as supply chain disruptions, labor costs, and global commodity prices.

Furthermore, the influence of marketing and consumer psychology cannot be overlooked. In the 1980s, marketing was more straightforward, often focused on price and basic product benefits. Today, grocery marketing is a sophisticated operation leveraging data analytics, loyalty programs, and personalized promotions delivered through smartphones and apps. This can drive consumers toward higher-margin items, contributing to increased spending even when they are buying fewer items or smaller quantities.

Ultimately, while the cost of filling a grocery cart has undeniably increased over the past four decades, the reasons are multifaceted. The evolution from simple, staple-focused shopping lists to complex arrays of premium, branded, and convenience foods, combined with changing shopping behaviors and economic pressures, means that a modern grocery bill tells a very different story than its 1980s counterpart.

Time and Labor: The Human Factor

Grocery shopping in the 1980s demanded a significant investment of time and physical effort from the shopper, but it was a clear, defined routine woven into family life. Preparing the weekly list often required a thoughtful review of what was on hand and what was needed, sometimes a collaborative effort involving the whole household. The act of driving to the store was often bundled with other errands or weekend family outings, making the trip a predictable part of the week’s rhythm.

Once inside the store, navigating aisles with a heavy metal cart, selecting each item, and physically lifting or carrying the groceries was simply accepted as part of the process. Bags were usually paper or thin plastic, and packing them efficiently—balancing heavy cans with fragile eggs—was a skill many shoppers developed over time. At checkout, customers would unload their carts onto the conveyor, and bag their groceries themselves or with help from baggers, who were often local teenagers earning their first wages. For many families, this was a chance to teach responsibility or to contribute in a meaningful way.

After the checkout, the labor didn’t end. Shoppers carried their bags to the car, loaded them in, and later unloaded at home, often sorting and storing each item carefully to maximize freshness and accessibility. This sequence of tasks, while physically demanding, fostered a tangible connection to food and household management that was rarely questioned—it was simply part of being a responsible adult or family member.

Fast-forward to today, and much of this hands-on labor has been displaced by a service economy where time is commodified. The rise of grocery delivery and curbside pickup means many shoppers no longer push carts or bag their own groceries. Instead, gig economy workers or store employees gather, pack, and transport items, shifting the physical workload away from consumers. This shift undoubtedly frees up time and energy for busy households, especially those juggling work, childcare, and other commitments. Yet, it also creates a layer of separation between consumers and the food they consume.

For the shopper, this outsourcing offers convenience but also a loss of direct engagement with the food selection process. Without walking the aisles, comparing produce quality firsthand, or interacting with store staff, customers miss opportunities to develop a nuanced understanding of seasonality, price fluctuations, and brand trustworthiness. The sensory experience—the weight of a melon, the firmness of a head of lettuce, the aroma of fresh bread—is diminished or lost altogether.

Moreover, the physical labor borne by gig workers is often underappreciated. These shoppers navigate crowded stores, interpret vague or incomplete shopping lists, substitute items when necessary, and endure tight time constraints—all while managing their own expenses and uncertain income. The human factor now exists behind the scenes rather than at the forefront of the shopping experience, raising questions about the value we place on labor in the modern economy.

In essence, the 1980s grocery trip was a physical, social, and sensory event embedded in family life, balancing responsibility with routine. Today’s model prioritizes efficiency and flexibility but at the cost of personal involvement and a tangible connection to the food system. This transformation highlights broader societal shifts in how time is valued, who performs essential work, and how consumer relationships with everyday tasks evolve.

Impact on Meal Planning and Cooking

In the 1980s, meal planning wasn’t just a household chore—it was a small exercise in logistics. The weekly grocery run set the parameters for what was possible in the kitchen for the next seven days. If the family shopped on Saturday, the fridge and pantry were stocked with a week’s worth of staples, supplemented by a few seasonal treats. That meant every meal decision during the week had to be made within the boundaries of what was already in the house.

Planning required both foresight and adaptability. A parent might flip through a spiral-bound recipe book, a stack of clipped newspaper recipes, or even the back of a Campbell’s soup can for ideas. They’d mentally map out how ingredients would be used across multiple meals—leftover roast beef might reappear as French dip sandwiches, then beef-and-vegetable soup. A pack of chicken thighs might be baked one night and shredded for enchiladas later in the week. The necessity of stretching ingredients taught a certain frugality and creativity, and these skills were often passed down to children through shared kitchen time.

The limited frequency of shopping trips meant pantry staples were king. A well-stocked pantry in 1985 might contain flour, sugar, rice, dry pasta, canned tomatoes, tuna, peanut butter, and powdered drink mixes like Kool-Aid or Tang. Freezers were equally important—holding family-sized packs of meat, bags of frozen peas, and maybe a gallon of ice cream for special desserts. The rhythm of cooking was built on turning these staples into complete meals, often with only a few fresh ingredients to tie it all together.

Fast-forward to today, and the philosophy of cooking has shifted from “make do with what you have” to “make what you want, then buy what’s missing.” The growth of on-demand grocery delivery means a missing ingredient no longer derails a recipe—it simply triggers a quick app order. A craving for Thai curry on a Tuesday night doesn’t require pre-planning; coconut milk, fresh basil, and lemongrass can arrive at your door before you’ve finished chopping onions. This has opened up an incredible range of culinary freedom, but it also changes how kitchens are managed. Many households no longer keep a deep pantry of multipurpose staples, instead relying on frequent top-ups of fresh or niche items.

Cooking methods have evolved, too. In the 1980s, a home-cooked meal meant chopping, seasoning, and cooking from scratch. Even shortcuts—like using a jar of spaghetti sauce or a box of Hamburger Helper—still required browning meat, boiling pasta, or baking in the oven. The modern grocery store, by contrast, is full of semi-prepped or fully cooked options. Bags of pre-chopped onions, containers of shredded rotisserie chicken, and vacuum-sealed marinated salmon mean that “cooking” often involves assembly rather than traditional preparation.

The effect on cooking skills is profound. In the 80s, most adults could comfortably prepare a dozen or more meals without consulting a recipe, having learned them through repetition. Today, some younger households treat scratch cooking as a weekend project, a social activity, or a form of self-expression rather than a daily necessity. While time-saving products and flexible shopping have freed people from the pressure of nightly cooking, they’ve also eroded the everyday cooking fluency that once defined home kitchens.

In short, the weekly meal plan of the 1980s fostered a disciplined, resourceful approach to food, born of necessity and habit. Today’s on-demand world favors variety, spontaneity, and convenience, but at the cost of the built-in structure that once defined how—and why—families cooked the way they did.

Storage and Kitchen Design Changes

In the 1980s, the kitchen was both a workspace and a warehouse. Its layout reflected the reality that families didn’t just buy for the week—they stocked up for the month, sometimes longer. A typical suburban kitchen had generous cupboards, deep shelves, and a pantry that could hold not only a rainbow of canned vegetables but also baking supplies, cereal boxes, and rows of pasta stacked like dominos. In many homes, a second refrigerator or a chest freezer was as essential as a stove. That freezer might be filled with butcher-wrapped cuts of meat bought in bulk, loaves of bread purchased during a sale and frozen for later, or gallon-sized freezer bags of sweet corn, green beans, or blueberries from a family garden, carefully labeled in black marker.

Storage wasn’t just convenience—it was strategy. A savvy home cook could build a month’s worth of meals around what was already on hand, dipping into long-term stores during leaner weeks or when weather made shopping impossible. In snow-prone regions, that chest freezer and pantry could carry a family through multiple days of being snowed in. For those living paycheck to paycheck, a well-stocked kitchen acted as a safety net, ensuring that no matter what the bank account looked like, dinner could still be made without a store run.

Even kitchen cabinetry reflected this mindset. Shelves were deeper, and pantries sometimes doubled as multi-use storage for small appliances, paper goods, and bulk cleaning supplies. The kitchen was not just about cooking—it was about keeping the household prepared.

Fast-forward to today, and many modern kitchens—especially in urban apartments and new-build condos—are designed for an entirely different rhythm of consumption. Cabinet space is often minimal, pantries are shallow or non-existent, and refrigerators, while more technologically advanced, are sometimes smaller in capacity. The design assumption is simple: you can shop whenever you need to. A missing ingredient is not a crisis when you have a 24-hour supermarket nearby or an app that delivers groceries in under an hour.

This design shift changes behavior. Instead of buying three jars of peanut butter during a sale, people buy one, confident they can replace it at any time. Instead of filling a freezer with raw ingredients to turn into meals, many fill it with convenience items: frozen pizza for busy nights, a pint of premium ice cream for dessert, frozen dumplings for a quick lunch. Freezers, once a tool of long-term preparedness, now more often serve as short-term convenience stations.

In larger homes, secondary refrigerators and chest freezers still exist, but their contents reflect cultural shifts. Where a 1980s freezer might have been stacked with a quarter side of beef from a local farm, today it’s just as likely to hold Costco-sized boxes of ready-made lasagna, pre-marinated meats, or smoothie-ready frozen fruit blends. Preparedness has been replaced with flexibility—the confidence that you can always get what you need when you need it, making stockpiling feel less necessary.

This change in storage philosophy says as much about modern life as it does about kitchen design: we’ve moved from a culture of “keep enough for anything” to one of “get anything anytime.” While this offers freedom, it also means that when disruptions occur—whether from supply chain issues, severe weather, or sudden illness—many households discover just how little buffer they have at home.

Community and Culture

In the 1980s, the grocery store was not just a place to shop—it was a social hub woven into the weekly rhythm of community life. A Saturday morning trip might stretch from a quick errand into a two-hour excursion simply because you kept running into people you knew. You might pass your neighbor in the bread aisle, chat with a fellow parent about the upcoming Little League game, or compare notes with a friend about which brand of coffee was on sale. The cashier knew your name, the butcher remembered that you preferred thin-sliced bacon, and the produce clerk would tip you off when the first local strawberries of the season arrived.

These connections, while small, were cumulative. Over time, they created a web of familiarity and trust. Your grocery store wasn’t just a store—it was your store, a place where you felt recognized and valued. For older customers or those living alone, these brief conversations might have been one of the most reliable sources of human interaction in their week.

In smaller towns, the sense of belonging was even more pronounced. The grocery store often doubled as a kind of unofficial bulletin board—flyers for community events, school fundraisers, and bake sales might be posted near the entrance. Local news traveled through word of mouth in the produce section just as much as through the local paper. If you forgot to bring a coupon, the cashier might quietly ring it up anyway, knowing you were a regular. This wasn’t just customer service—it was community care.

Today’s grocery shopping culture has shifted dramatically. Large chain stores see higher employee turnover, making it less likely that you’ll consistently interact with the same staff. Self-checkout stations, while efficient, strip away the opportunity for small talk. Even when staffed lanes are available, the pace of the transaction is faster, the focus squarely on efficiency over connection.

Delivery, which has exploded in popularity, removes human interaction almost entirely. Many orders arrive contact-free, left on the doorstep with no more than a text alert to announce their arrival. When a driver does hand over the bags, the exchange is typically brisk—perhaps a “thanks” and “have a good day,” but little more. The relationships that once grew organically over months or years of shopping in the same place simply don’t have a chance to form.

Some argue this is the price of convenience, a necessary trade-off in a world where schedules are packed and time feels scarce. Yet in losing these micro-interactions, we also lose something harder to measure: the subtle reinforcement of belonging to a shared space. Those fleeting conversations, the familiar nods, the recognition from someone who knows you beyond a screen name—these are the threads that, woven together, make up the social fabric of a community.

In a purely transactional model, groceries become just another commodity, delivered from warehouse to home with no human bridge in between. But for anyone who remembers lingering in a checkout line to hear about the cashier’s new puppy or getting a recipe tip from the woman ahead of you in line, it’s clear that the 1980s grocery store offered more than food—it offered connection.

Advertising and Marketing Evolution

In the 1980s, grocery advertising spoke to everyone at once. If you turned on the TV, you were just as likely to see a spot for Tide detergent as you were for Pop-Tarts, regardless of your age, income, or buying habits. Saturday morning cartoon blocks were prime real estate for cereal companies, each with a mascot more energetic and memorable than the last—Tony the Tiger promising that “They’re grrreat!” or the Trix Rabbit endlessly scheming to steal cereal from children. These commercials didn’t just sell products; they became part of the cultural wallpaper, repeated in schoolyard jokes and playground games.

Print advertising played a huge role as well. Sunday newspapers were a weekly event for many families, and tucked between the comics and the classifieds were thick, glossy grocery circulars. These flyers were a visual buffet of the week’s deals—photographs of roasts, piles of oranges, and bold red price tags announcing 39¢ for bananas or “3 for $1” canned goods. They were designed for clipping coupons, making lists, and comparing which store had the best sales.

In-store marketing was straightforward but effective. End-cap displays—those extra-visible shelves at the end of aisles—featured soda towers, snack displays, or seasonal specials. Sampling tables often appeared on weekends, where a retiree in a branded apron might offer you a cube of cheese on a toothpick or a paper cup of new soda. Promotions were easy to understand: “buy one, get one free” or “double coupon day” brought crowds. The approach wasn’t subtle, but it worked—getting shoppers excited to walk in and load up their carts.

By contrast, today’s grocery marketing operates on an entirely different wavelength. Instead of casting a wide net, retailers now aim for surgical precision. Loyalty cards, store apps, and online accounts track your exact purchases over time, building a digital profile of your preferences. If you buy oat milk twice, you may start seeing oat milk brands promoted on your social media feed or emailed directly to you with a “just for you” coupon.

The rise of e-commerce and delivery platforms has layered in new marketing tactics. Search results on Instacart or Amazon Fresh are not neutral—they’re often influenced by paid placement, so the first brand you see isn’t necessarily the cheapest or most popular, but the one that paid for visibility. Suggested products appear mid-scroll, nudging you toward “recommended pairings” that subtly expand your order. Even substitutions, when your chosen item is out of stock, can serve as quiet marketing opportunities for a rival brand.

Social media has blurred the line between advertising and entertainment. Influencers on TikTok and Instagram casually showcase “grocery hauls” or “healthy meal prep” videos, with branded items front and center—sometimes disclosed as paid partnerships, sometimes not. This kind of marketing doesn’t just sell a product; it sells a lifestyle. Packaging has adapted accordingly, with bolder fonts, minimalist designs, and labels touting organic certification, sustainability, high-protein content, or luxury appeal.

The end result is a shopping landscape where the illusion of infinite choice masks the reality that much of what you see—both online and in-store—has been carefully curated and positioned. In the 1980s, the goal of marketing was to get you through the door and browsing the aisles. In the 2020s, the battle is for your attention within seconds, shaping your decision before you even start shopping. Whether you’re walking through sliding glass doors or scrolling on a phone, you’re entering a space where the “choice” you see has already been edited for you.

Environmental Considerations

In the 1980s, environmentalism wasn’t a major driver of grocery store practices, but everyday shopping habits inadvertently produced less waste than many modern systems. Paper bags were standard, and while plastic grocery bags began appearing in the mid-80s, they hadn’t yet become the overwhelming default. Many products still came in glass jars or bottles, which could be reused at home for storage or returned for deposit refunds in some regions. Milk in returnable glass bottles was still available in certain areas, and soda bottle deposits were a normal part of life in states with container laws. Bulk buying—whether in the form of large family-sized packages or stockpiling sale items—meant that households used less packaging per serving.

The limited variety of single-serving snacks and ready-to-eat meals also had a side effect: fewer wrappers, trays, and plastic film cluttering the trash. When families made lunches for work or school, they often used reusable containers, wax paper, or foil rather than pre-packaged items. Even food waste was often minimized—leftovers were a routine part of meal planning, and home composting or feeding scraps to pets was more common in rural and suburban areas.

Fast forward to today, and environmental awareness is far more visible in public discourse. Shoppers can find eco-friendly product lines, biodegradable packaging, and “sustainable sourcing” labels in nearly every aisle. But the reality is more complex. Modern grocery systems—especially those involving on-demand delivery—tend to generate more packaging waste. A single order might arrive with multiple layers: individual plastic produce bags inside paper shopping bags, bubble wrap for fragile items, insulated pouches for frozen goods, and sometimes even gel ice packs that must be disposed of.

The environmental impact isn’t just in the packaging—it’s also in the transportation. A weekly 1980s grocery trip often involved a single round-trip drive, with all the week’s food bought at once. Today’s frequent small deliveries can multiply the carbon footprint, especially when delivery routes aren’t optimized or when items are sourced from multiple warehouses rather than one store. The shift toward “instant” service has an invisible environmental cost baked into its convenience.

Some companies are experimenting with solutions: electric delivery vans, reusable tote programs, take-back systems for ice packs, and bulk refill stations for staples like grains, coffee, and cleaning supplies. Urban zero-waste stores and co-ops are gaining traction, though they remain niche compared to mainstream supermarkets. Even with these initiatives, the systems in place still tend to prioritize speed, freshness, and customer satisfaction over long-term sustainability.

The paradox of modern grocery shopping is that environmental consciousness has grown, but so has the infrastructure for disposable convenience. The cultural challenge isn’t just to raise awareness—it’s to shift habits and systems in ways that make the sustainable choice as easy, affordable, and tempting as the fast, waste-heavy one.

Psychological and Lifestyle Shifts

In the 1980s, the cadence of grocery shopping was woven into the weekly routine, almost like a household heartbeat. Saturday morning or Thursday evening might be “grocery night,” a fixed appointment in the family schedule. The process was predictable: make the list, check the pantry, go to the store, and return with everything needed to get through the next seven days. Once the bags were unpacked and the cupboards full, there was a genuine sense of closure and accomplishment—one big job crossed off the list. The psychological reward wasn’t just in having food, but in knowing you were prepared.

This rhythm created a kind of mental calm. You weren’t constantly monitoring the milk level or wondering if you had enough bread for the week—those calculations had already been made during the planning stage. Running out of something before the next scheduled trip was rare, and when it did happen, it was more an inconvenience than a crisis. The acceptance of waiting—whether for coffee to go on sale again or for your favorite cookies to restock—was simply part of life. That patience wasn’t seen as deprivation; it was just the way things worked.

In the modern on-demand model, food acquisition has become a continuous background process rather than a single weekly event. You might order groceries on Monday for a few dinners, then realize on Wednesday that you’re low on snacks, and by Saturday decide to restock breakfast items. The “done” moment never arrives—there’s always another order to place, another item to remember. This creates what psychologists sometimes call a “low-level cognitive drag,” a subtle but constant mental task running in the background, eating away at focus and rest.

The psychological shift also ties into broader cultural patterns of instant gratification. In the 1980s, running out of your favorite ice cream simply meant going without until the next trip. That gap between desire and fulfillment was normal—and in a small way, it built anticipation and appreciation. Today, with one-hour delivery a tap away, waiting is framed as a hassle rather than a natural part of life. We’ve trained ourselves to see convenience not as a luxury, but as an expectation.

This constant availability also changes how we think about abundance. In the 80s, a full pantry signaled security—you had what you needed. Today, abundance is measured less by what’s in your home and more by your ability to access whatever you want, whenever you want it. It’s a subtle but profound shift: security now comes from the reliability of the supply chain and the phone in your pocket, rather than the stockpile in your cupboard.

Over time, this change affects not just shopping habits, but attitudes toward patience, preparedness, and even self-sufficiency. The old rhythm offered a clear cycle of planning, action, and rest; the new one keeps us perpetually in motion, always one click away from the next replenishment.

Case Study: A Week’s Worth of Groceries Then and Now

Let’s take a closer, more textured look at a typical grocery week for a middle-class family of four—once in the mid-1980s and again in 2025—so we can see not just what they bought, but how those purchases fit into daily life.

1985: The Weekly Stock-Up

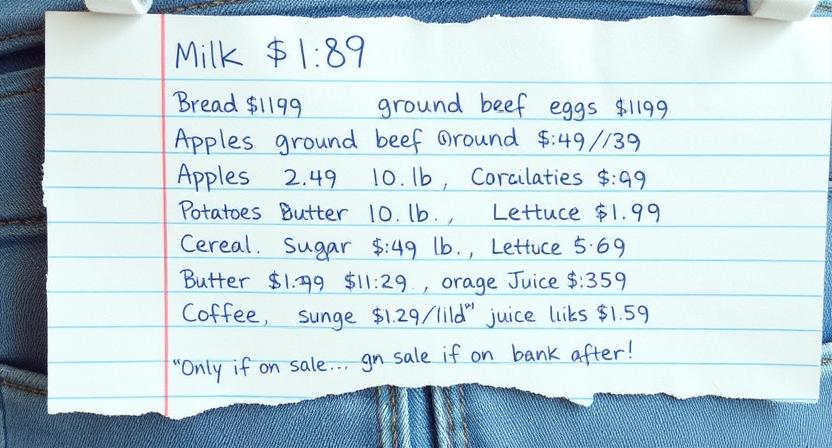

It’s Saturday morning in 1985. Mom has her handwritten list on a lined notepad, compiled from a week’s worth of meal planning and a quick scan of the fridge and pantry. The family piles into the station wagon and heads to the local supermarket. Prices are clearly marked on paper tags, and she has the store flyer folded in her purse, already circled with the week’s sales.

In the cart go two gallons of whole milk at $1.89 each, three loaves of white bread at 79 cents apiece, and a dozen large eggs for 99 cents. Five pounds of ground beef—on sale for $1.59 per pound—will become tacos, meatloaf, and spaghetti sauce. A whole chicken, just $2.75, is destined for Sunday dinner, with enough left over for sandwiches. Potatoes, ten pounds for $2.49, will appear at least four times in the week—baked, mashed, and pan-fried.

Fresh produce is modest but dependable: iceberg lettuce, a bunch of bananas, and a five-pound bag of apples. Several cans of green beans and corn fill the pantry shelves alongside pasta, jars of tomato sauce, peanut butter, jelly, and two boxes of Cheerios or Corn Flakes. A half-gallon of ice cream—maybe Breyers—at $2.29 is the splurge of the week.

The checkout total comes to roughly $65, which is about $185 in today’s money. The cart is full, and the week is set. By the following Saturday, the fridge will be nearly bare, but little will be thrown away. Leftovers are planned for, not accidental. Monday’s roast chicken becomes Tuesday’s sandwiches and Wednesday’s soup. That single shopping trip anchors the week’s meals with a sense of order and predictability.

2025: The On-Demand Approach

Now jump to the present. The same family—perhaps with slightly different tastes—has no designated “grocery day.” On Monday morning, Dad notices the fridge looks sparse, so he opens the Instacart app and orders fresh strawberries ($5.99 for a pint), Greek yogurt ($6.49 for a tub), and almond milk ($4.79). A bag of baby spinach and a loaf of multigrain bread round out the order. The convenience fee and tip add another $7.

By Wednesday, the strawberries are half-eaten, and a few are already starting to soften. Mom decides to order dinner ingredients: two fillets of fresh salmon ($12.99 per pound), a bunch of asparagus ($4.29), and a bottle of Sauvignon Blanc ($14.99). She tosses in a pack of fancy crackers and a wedge of brie because they look tempting in the app’s “recommended for you” section.

Friday rolls around, and no one feels like cooking from scratch. A two-night meal kit arrives at the doorstep—pre-measured spices, vacuum-sealed proteins, and a glossy recipe card—for $48 plus delivery. The kids also request snacks for the weekend, so bags of kettle chips, fruit gummies, and sparkling water are added to the order. Somewhere between these purchases, there’s at least one night of takeout pizza and one drive-thru run for burgers.

By Sunday evening, the fridge looks cluttered but not coordinated. The half-eaten brie is starting to dry out, the asparagus never got cooked, and the strawberries have grown a patch of fuzz. Monday’s yogurt is forgotten behind the takeout containers. The household has spent somewhere between $250 and $300—triple the 1985 total when adjusted for inflation—and yet they’re still debating what’s for dinner.

What This Reveals

The contrast is striking. In 1985, one deliberate trip, structured meal planning, and a “use what you have” mindset kept costs and waste low. In 2025, fragmented purchasing, algorithm-driven impulse buys, and the comfort of knowing food can be delivered in under an hour lead to higher costs and more spoilage. The abundance is undeniable, but it’s scattered abundance—plenty of food, but not always in the right combinations to form a meal without another trip or order.

In short, the 1985 cart represented a week of meals waiting to happen. The 2025 fridge often represents a week of intentions, some fulfilled and some forgotten.

The Pandemic’s Role in Accelerating the Shift