Introduction: The Dawn of Digital Connections

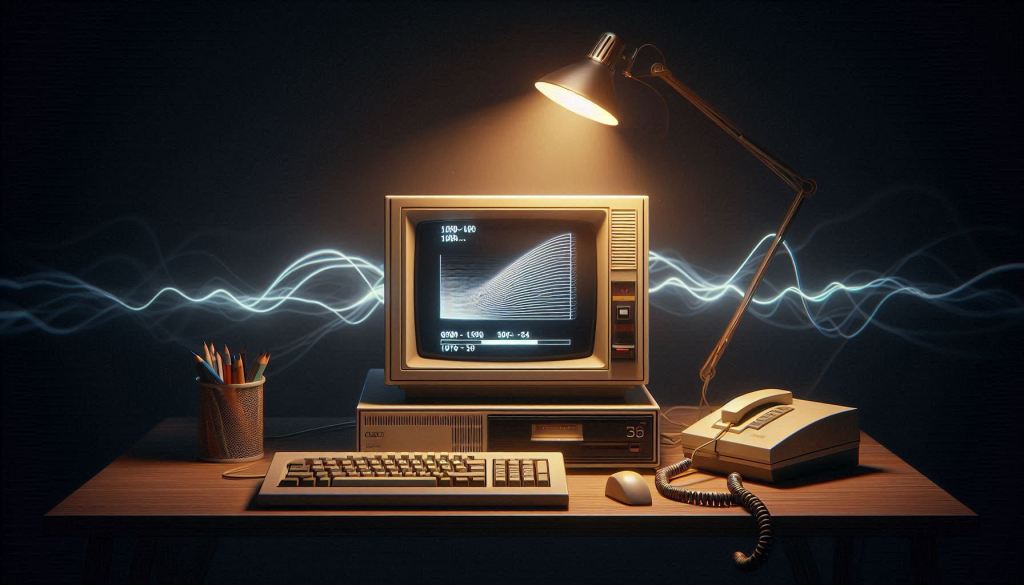

Before the Internet was always on, before pages loaded instantly and messages arrived without delay, getting online was a deliberate act. You dialed, you waited, and—if everything went right—you connected. This was the modem era, a time when computers reached beyond the room they sat in and touched distant machines through ordinary telephone lines.

In the 1980s and early 1990s, modems transformed personal computers from isolated tools into gateways to a larger digital world. With a modem, a home computer could exchange data with bulletin board systems, universities, businesses, and eventually early online services. The experience was slow, sometimes unreliable, and often noisy—but it was revolutionary.

Every connection felt significant. You could hear it happening, step by step, as machines negotiated their link across miles of copper wire. That moment marked the beginning of something new: the early Internet era, where curiosity, patience, and technology met for the first time.

The Birth of the Modem

The modem did not begin as a device for the home. Long before personal computers and the early Internet, the need to send information over long distances already existed. Businesses, governments, and research institutions had a problem: computers could process data quickly, but they were isolated machines. If information needed to travel, it usually did so on paper, magnetic tape, or by physically moving storage from one place to another. The modem was born from the desire to break this limitation.

The word modem is short for modulator–demodulator. This name describes exactly what the device was designed to do. Early telephone systems were built to carry human voices, not digital data. Computers, however, speak in binary—streams of ones and zeros. A modem translated digital data into audible tones that could travel over standard phone lines, then converted those tones back into digital data at the receiving end. This simple but powerful idea made it possible for computers to communicate across vast distances without building an entirely new network.

The earliest modems appeared in the late 1950s and early 1960s, primarily for military and industrial use. One of the first widely recognized examples was developed by Bell Labs for the U.S. military’s SAGE air defense system. These early modems were large, expensive, and extremely slow by modern standards, often transmitting data at speeds measured in a few hundred bits per second. Yet even at these speeds, they proved that digital communication over phone lines was possible.

As computers became more common in universities and businesses during the 1970s, the modem began to evolve. Improvements in electronics allowed modems to become smaller, more reliable, and faster. Standards began to emerge so that devices from different manufacturers could communicate with one another. By the late 1970s, acoustic coupler modems appeared, allowing users to place a telephone handset into rubber cups. This avoided the need for direct electrical connections and made modems accessible to early hobbyists and computer enthusiasts.

The true turning point came with the rise of the personal computer in the late 1970s and early 1980s. As home computers entered bedrooms, offices, and basements, modems followed closely behind. Companies began producing affordable modems designed specifically for consumers. These early home modems typically operated at 300 or 1200 baud, later advancing to 2400 baud and beyond. Though slow, they opened the door to a new kind of personal communication.

With a modem, a home computer could dial into bulletin board systems, exchange messages, download software, and share information with strangers across cities or even countries. This was a radical idea at the time. Communication was no longer limited to phone calls or postal mail. Data itself could travel, carrying text, programs, and ideas.

By the mid to late 1980s, modems had become a defining piece of computer hardware. They represented possibility—the promise that a single computer could be part of something larger. The birth of the modem marked the first true step toward the interconnected digital world, laying the foundation for the early Internet and everything that would follow.

How Dial-Up Technology Worked

Dial-up technology was built on a clever compromise: using an existing system designed for human speech to carry digital information between computers. Telephone networks were everywhere, reliable, and already connected across cities and countries. Instead of inventing a new infrastructure, early engineers found a way to make computers speak a language the phone system could understand.

At its core, dial-up communication relied on the modem’s ability to translate digital data into sound. Computers process information as electrical signals representing ones and zeros. Telephone lines, however, were designed to carry audio frequencies produced by the human voice. The modem solved this mismatch by converting digital data into audible tones through a process called modulation. On the receiving end, another modem performed the reverse operation—demodulation—turning those tones back into digital data.

A dial-up connection began with a phone call. When a computer initiated a connection, the modem dialed a specific telephone number linked to another modem, such as one operated by a bulletin board system or an online service. Once the call was answered, the two modems entered a negotiation phase known as the handshake. During this brief but distinctive exchange, the modems identified each other’s capabilities, agreed on a communication speed, and selected error-correction methods to ensure reliable data transfer.

This handshake produced the familiar series of hisses, beeps, and screeches that defined the dial-up era. These sounds were not random noise; they were precise audio signals encoding technical information. If the handshake succeeded, the connection was established. If it failed, the call would drop, and the process would need to be repeated.

Once connected, data holding text, commands, or files was transmitted in small packets. Because phone lines were sensitive to noise and interference, dial-up connections were prone to errors. To compensate, modems used error-detection and correction protocols. These systems identified corrupted data and requested retransmission, ensuring accuracy at the cost of speed. As a result, actual transfer rates were often slower than the modem’s advertised speed.

Speed itself evolved gradually. Early consumer modems operated at 300 baud, transmitting about 300 bits per second. As technology improved, speeds increased to 1200, 2400, 9600, 14.4k, 28.8k, and eventually 56k. Each increase felt dramatic at the time, even though modern connections would later make these speeds seem impossibly slow.

Dial-up connections were also exclusive. Because they used a standard phone line, only one activity could occur at a time. If someone picked up the telephone during an active connection, the modem would often lose its link immediately. This limitation shaped user behavior, pushing many connections into late-night hours when phone lines were less likely to be needed.

Despite its limitations, dial-up technology worked remarkably well for its time. It allowed ordinary people to connect their home computers to distant systems using nothing more than a phone line and a modem. Through this simple but ingenious method, dial-up became the backbone of the early Internet era, proving that global digital communication was not only possible, but practical.

The Sound of Connection

For many people, dial-up Internet is remembered not by what was seen on the screen, but by what was heard. The sound of a modem connecting became one of the most recognizable audio signatures of the early Internet era. It was mechanical, strange, and unmistakable—a brief performance that announced a computer was reaching beyond itself to make contact with another machine.

The process began quietly with the familiar tone of a telephone dialing. Once the call was answered, the modem took over and the real sounds began. A series of clicks signaled the line opening, followed by rising and falling tones as the two modems identified one another. Sharp chirps, steady hisses, and sudden bursts of screeching filled the room. Each sound represented a specific technical step in the negotiation process, even if users did not fully understand what was happening.

These sounds were the audible form of the modem handshake. During this exchange, the modems agreed on speed, compression methods, and error correction protocols. If the line quality was poor, the sounds might stretch longer or repeat as the devices attempted to establish a stable connection. A sudden silence or abrupt click often meant failure, followed by disappointment and another attempt.

The modem’s noise served as a kind of progress indicator. Experienced users could often tell whether a connection was going well simply by listening. Certain tones suggested a faster connection, while others hinted that the modem had dropped to a lower speed. Over time, these sounds became familiar, even comforting, signaling that the digital world was within reach.

The sound of connection also had a social presence. It echoed through bedrooms, offices, and shared household spaces, sometimes late at night. It announced that the phone line was in use, often triggering reminders not to pick up the receiver. In many homes, the modem’s noise became part of the household rhythm, as recognizable as a ringing phone or a television turning on.

As technology advanced, newer modems refined and shortened the handshake process, but the sounds never disappeared entirely. They remained a reminder that digital communication required effort, patience, and cooperation between machines. Unlike today’s silent, always-on connections, dial-up made its presence known.

In hindsight, the sound of a modem connecting was more than technical noise. It was the audible beginning of communication, the moment when isolation gave way to connection. For an entire generation, that strange chorus of tones marked the gateway to the early Internet and the promise of a world just beyond the phone line.

Modems in the Home and Office

As modems became more affordable and reliable, they began to move out of research labs and corporate facilities and into everyday spaces. By the mid to late 1980s, the modem had established itself as a common fixture in both homes and offices, quietly reshaping how people worked, communicated, and shared information.

In the home, the modem often sat beside a personal computer on a desk or small table, connected by a tangle of cables to the nearest telephone jack. For many families, this setup represented a significant investment and a sense of technological progress. Home users relied on modems to access bulletin board systems, exchange messages, download software, and explore early online communities. These activities introduced a new kind of independence, allowing individuals to communicate and learn without leaving their homes.

The shared nature of household phone lines made modem use a careful balancing act. Since a single line typically served the entire home, modem sessions were often scheduled during quiet hours. Late evenings and nights became prime time for connecting, when phone calls were less likely to interrupt a session. This led to a distinct rhythm of use, where curiosity and exploration thrived after the rest of the household had gone to sleep.

In offices, modems played a more structured and practical role. Businesses used them to transmit data, send reports, and access centralized computer systems. Employees could connect remote terminals to mainframes or early networks, making it possible to work with shared data from different locations. Modems enabled early forms of remote work, long before the concept became widespread or expected.

Office modems were often faster and more robust than their home counterparts. They were integrated into larger systems and configured to run for extended periods without interruption. In some environments, dedicated phone lines were installed specifically for modem use, reflecting the growing importance of digital communication in business operations.

The presence of modems in both homes and offices blurred the boundary between personal and professional computing. A technology once reserved for institutions now sat on desks and nightstands, accessible to students, hobbyists, professionals, and families alike. This widespread adoption helped normalize the idea of computers as communication tools rather than isolated machines.

By the end of the 1980s and into the early 1990s, modems had become symbols of connectivity. Whether in a quiet bedroom or a busy office, they represented access—to information, to people, and to a rapidly expanding digital world.

Speed, Limitations, and Patience

Dial-up modems brought the promise of connection, but they also demanded something from their users: patience. Speed was the most obvious limitation of the modem era, and it shaped nearly every aspect of the early Internet experience. By modern standards, dial-up was slow—but at the time, each improvement felt like a breakthrough.

Early home modems operated at speeds such as 300, 1200, or 2400 baud, transmitting only a small amount of data each second. Even as technology advanced and speeds climbed to 9600, 14.4k, 28.8k, and eventually 56k, connections remained tightly constrained. Downloading a simple text file could take minutes, while images loaded line by line, slowly revealing themselves from top to bottom. Large files were often left to download overnight, with no guarantee they would finish successfully.

The limitations were not only about speed. Dial-up connections were fragile. Line noise, electrical interference, or someone picking up a phone extension could instantly terminate a session. Disconnections were common, and reconnecting meant repeating the entire dialing and handshake process. In some cases, users had to restart downloads from the beginning, losing all progress made up to that point.

Because of these constraints, efficiency became a necessity. Software was designed to be small and text-heavy. Websites favored simple layouts with minimal graphics. Users learned to read carefully, plan their actions, and avoid unnecessary clicks. Time online often mattered, especially for services that charged by the hour. Every minute spent waiting for a page to load was a minute counted against the user.

Patience was not just a technical requirement—it became a mindset. Users adapted to the rhythm of dial-up, understanding that delays were part of the experience. Waiting was expected, accepted, and even normalized. The slow pace encouraged exploration at a thoughtful speed, where reading, writing, and conversation took precedence over instant results.

Yet within these limitations, there was a sense of achievement. Successfully downloading a file, sending a message, or maintaining a stable connection felt rewarding. Each completed task confirmed that the technology, despite its flaws, was working. The effort required to stay connected made the experience feel earned.

In hindsight, the speed and limitations of dial-up defined the character of the early Internet. They shaped user behavior, influenced design choices, and fostered a culture of patience and persistence. The modem era taught its users that connection was possible—but never effortless—and that waiting was simply part of the journey.

The Rise of Online Services

As modems became more common in homes and offices, a new layer of the digital world began to take shape. While early users often connected directly to bulletin board systems or academic networks, many people were introduced to the online world through centralized platforms known as online services. These services acted as gateways, making digital communication more accessible to a wider audience.

Online services provided structured environments that simplified the experience of connecting. Instead of dialing different numbers for different systems, users logged into a single service that offered multiple features under one account. These platforms handled the technical complexity, allowing users to focus on exploration rather than configuration. For many, this was the first time computers felt welcoming rather than intimidating.

These services offered a growing range of functions. Email became a popular feature, enabling fast written communication that felt revolutionary compared to traditional mail. Discussion forums and message boards allowed users to participate in group conversations organized by topic. News, weather, software libraries, and informational databases were made available through text-based menus that loaded quickly over slow connections.

Chat rooms introduced a new kind of interaction: real-time conversation with strangers. This was a dramatic shift from delayed communication methods. Users could type messages and see responses appear almost instantly, creating a sense of shared presence despite physical distance. These spaces became social hubs, where friendships formed and online identities began to emerge.

The rise of online services also brought the Internet into popular culture. Marketing campaigns, trial disks, and magazine advertisements promoted the idea of being “online” as something exciting and modern. Computers were no longer just tools for work or study—they were becoming portals to communities, entertainment, and information.

Importantly, these services helped bridge the gap between technical users and the general public. They introduced concepts like usernames, passwords, inboxes, and profiles that would later become standard across the Internet. The controlled environments of online services served as training grounds, preparing users for the more open and complex world that would follow.

By the early 1990s, online services had become central to the modem experience. They demonstrated the true potential of digital connectivity, showing that the modem was not just a piece of hardware, but a key to a shared online space. This shift marked a major step in the evolution of the early Internet, transforming isolated connections into a growing network of people and ideas.

America Online and the Social Internet

As online services expanded, one platform came to define the social side of the early Internet for millions of users: America Online. More than just a gateway to information, it presented the Internet as a place to gather, communicate, and belong. For many people, America Online was not simply a service—it was the Internet.

America Online distinguished itself by focusing on ease of use and human connection. Its software provided a graphical interface at a time when many online experiences were still text-heavy and technical. Icons, menus, and clear labels helped users navigate email, chat rooms, forums, and news without needing to understand the underlying technology. This accessibility brought entire households online, including people with little or no computer background.

At the center of the experience was communication. Email became personal and immediate, reinforced by the now-iconic notification announcing the arrival of new messages. Chat rooms allowed users to enter themed spaces where conversations unfolded in real time. People gathered around shared interests, locations, hobbies, or simple curiosity. For many, this was their first experience talking to strangers through a computer.

User profiles and screen names introduced the concept of digital identity. People chose names that reflected personality, humor, or anonymity, creating a separation between online presence and offline life. This freedom encouraged self-expression and experimentation, helping define early online culture. Conversations flowed differently than in person, driven entirely by text, imagination, and timing.

America Online also fostered community through forums, member-created spaces, and curated content. Users could follow discussions, share opinions, and return regularly to familiar digital neighborhoods. Over time, friendships formed, routines developed, and social norms emerged. The Internet was no longer just a place to retrieve information—it became a place to spend time.

Technically, all of this depended on dial-up modems and phone lines. Connections were slow and occasionally unreliable, but the social rewards outweighed the inconvenience. Users were willing to wait, reconnect, and plan their time online because the experience felt meaningful and alive.

America Online helped define what the social Internet could be. It transformed modems from simple communication tools into bridges between people, shaping expectations that still exist today. The emphasis on connection, conversation, and community marked a turning point in the early Internet era—one where technology began to feel deeply personal.

Cultural Impact of Dial-Up

The era of dial-up modems was more than a technological milestone; it was a cultural phenomenon that shaped the behaviors, routines, and social dynamics of an entire generation. In a time before always-on Internet and mobile devices, connecting online required intention, effort, and a degree of ritual. These limitations fostered habits and experiences that left a lasting mark on digital culture.

At home, the presence of a modem changed how families interacted. Because a single phone line could only support one connection at a time, scheduling became important. Children and teens often connected late at night, while parents or siblings reserved the phone for calls during the day. This created a shared understanding of boundaries and timing, where access to the online world was a valuable, sometimes scarce resource.

The sounds of dial-up—the beeps, hisses, and screeches—became cultural icons in their own right. Anyone growing up in the 1980s or early 1990s could instantly recognize these noises, which signaled that a computer was reaching out into a new digital realm. The modem’s auditory signature even found its way into popular media, appearing in films, television shows, and advertisements as shorthand for high-tech activity.

Dial-up also influenced online behavior and content. Slow connection speeds encouraged text-heavy websites, concise communication, and efficient design. Users became adept at patience, learning to read messages carefully, plan downloads, and manage time online. These constraints helped shape a generation’s approach to information consumption, emphasizing thoughtfulness over instant gratification.

Socially, modems helped cultivate early digital communities. Bulletin boards, chat rooms, and online services like America Online allowed individuals to meet people beyond their geographic neighborhoods. Friendships and even romantic connections formed over text, long before social media existed. The limitations of dial-up made these interactions intentional: people connected because they wanted to, not because notifications constantly demanded their attention.

The modem era also fostered curiosity and creativity. Early users experimented with technology, explored programming, and shared files in a way that felt like uncharted territory. Modems were gateways not just to information, but to invention, collaboration, and a sense of empowerment. The sense that you were part of something new and expanding created a collective identity among early Internet adopters.

In retrospect, the cultural impact of dial-up extends far beyond its technical constraints. It shaped communication habits, social norms, and even expectations for online interaction. The patience, intentionality, and sense of discovery fostered by dial-up modems left an enduring legacy, influencing how the digital world would evolve in the decades to come.

Legacy of the Modem Era

The modem era may now seem distant, a nostalgic memory of screeching connections and slow downloads, but its legacy is profound. Modems were more than hardware; they were the bridge between isolated computers and the vast, interconnected world that would become the Internet. They shaped technology, culture, and user expectations in ways that still resonate today.

Technologically, the modem laid the groundwork for global digital communication. Concepts like error correction, data compression, and standardized communication protocols were refined during this period. These innovations enabled faster and more reliable connections in later technologies, from broadband to fiber optics. The modem era proved that existing infrastructure, like telephone lines, could be harnessed to transmit digital data, a principle that underpins much of modern networking.

The influence of the modem extended to online communities. Early experiences with bulletin boards, chat rooms, and services like America Online established patterns of social interaction that continue online today. Usernames, profiles, moderated forums, and digital etiquette all have roots in the dial-up era. These early habits taught people how to communicate, collaborate, and navigate virtual spaces long before social media platforms existed.

Culturally, the modem era left a mark on a generation of users who experienced the Internet as an event, rather than a constant background presence. Waiting for a connection, navigating slow-loading pages, and managing shared phone lines instilled patience, resourcefulness, and an appreciation for the novelty of being online. These experiences shaped the expectations and attitudes of early Internet adopters, many of whom would go on to influence technology, design, and online culture.

The modem also symbolizes a spirit of curiosity and exploration. For the first time, ordinary people could reach beyond local boundaries, communicate with strangers around the world, and access information previously confined to institutions. That sense of empowerment fostered innovation, inspiring users to experiment with software, create content, and envision the potential of connected computers.

Even as technology has advanced and dial-up has faded into history, the modem era remains a touchstone for understanding the evolution of the Internet. It reminds us that connectivity, community, and communication were once tangible efforts—moments earned through sound, patience, and persistence. The legacy of the modem era endures not only in the networks we use today but in the culture, practices, and expectations it shaped for generations of Internet users.

Conclusion: Remembering the Early Internet

Looking back on the early Internet, it is impossible to separate the experience from the sound, rhythm, and presence of the modem. The era of dial-up was a time of discovery, patience, and innovation, where connection required effort and attention. Every successful handshake, every glowing CRT screen, and every blinking LED told the story of a world just beginning to open up.

The early Internet was defined by its limitations as much as its possibilities. Slow speeds, fragile connections, and shared phone lines shaped how people used technology, how they communicated, and how they formed communities. Yet these very constraints fostered creativity, careful planning, and a sense of reward for each achieved connection. People learned to navigate new digital spaces with curiosity and resourcefulness.

Services like America Online brought the Internet into homes in an approachable way, emphasizing human connection and social interaction. The first online communities, chat rooms, and bulletin boards introduced concepts of identity, collaboration, and etiquette that continue to influence online culture today. The modem was more than a machine—it was a gateway to human connection and shared discovery.

Remembering the early Internet is also a reflection on how far technology has come. From the screeching sounds of a 2400-baud handshake to the instant, always-on connectivity of modern networks, the pace and scale of digital communication have changed dramatically. Yet the sense of wonder that accompanied the first online experiences remains an enduring memory for those who lived it.

The modem era reminds us that the Internet was not simply invented—it was experienced, explored, and earned. It was a period when connection was tangible, immediate, and occasionally frustrating, but always transformative. By remembering these early days, we honor the foundations of the digital world and the pioneering spirit of those who first dialed, waited, and connected.

Leave a comment