An Era Built on Anticipation

Before everything became instant, life itself moved at a slower, more deliberate pace. The 1980s were not just a decade of neon colors, cassette tapes, and analog screens—they were an era defined by waiting. Waiting wasn’t a flaw in the system. It was the system.

In the 1980s, anticipation shaped everyday life. You didn’t just get things; you looked forward to them. Time stretched out between desire and fulfillment, and in that stretch lived imagination, excitement, and sometimes frustration—but also meaning. The wait gave experiences weight. It made them feel earned.

Today, waiting is often framed as a problem to solve. In the ’80s, it was simply part of being alive. You waited because there was no other option—and strangely, that limitation made moments feel richer. The gap between now and later created space for daydreaming, speculation, and shared excitement. You talked about what might happen, what could arrive, what you hoped would be worth the wait.

Anticipation was woven into the rhythm of daily life. It showed up in small moments and big ones, from standing by the mailbox to sitting inches from the radio speaker, finger hovering over the record button. The future wasn’t instantly accessible—it approached slowly, and you met it halfway.

This was a time when patience wasn’t a virtue you practiced consciously; it was a skill you learned naturally. And in learning it, you discovered something modern life rarely offers anymore: the quiet thrill of not knowing yet, and loving that you didn’t.

Waiting for Film to Develop

In the 1980s, taking a photograph was the beginning of a story, not the end of one.

Every photo started with a limit. A roll of film meant 12, 24, or—if you were lucky—36 chances. Each click of the shutter mattered. You didn’t spray and pray. You paused. You framed the shot in your mind before committing to it, because every picture used something up. Birthdays, vacations, first days of school, awkward family gatherings—moments had to earn their place on the roll.

Once the film was finished, the waiting truly began.

The canister was dropped off at a pharmacy, a camera shop, or a big-box store photo counter. The clerk would tear off a small receipt with a number on it and tell you when to come back: three days, a week, sometimes two. That slip of paper became a promise. Lose it, and you might never see those photos again. You tucked it into your wallet or pinned it to the fridge like it mattered—because it did.

For days, the photos existed only in memory. You replayed moments in your head, wondering how they would look frozen in time. Did the flash go off? Was anyone blinking? Did your thumb accidentally cover the lens? You had no way of knowing. There was no preview screen, no instant delete, no do-over. The uncertainty was part of the experience.

When pickup day finally arrived, it felt ceremonial. A small envelope—often yellow, sometimes white—was slid across the counter. Inside were glossy prints, warm from the machine, along with the negatives tucked carefully into a sleeve. That envelope carried more than images; it carried proof. Proof that the moments happened. Proof that the memories were real.

Opening the photos was an event in itself. Families gathered around kitchen tables. Friends sat cross-legged on bedroom floors. Photos were passed hand to hand, one at a time, in order. Laughter erupted unexpectedly. Groans followed the unflattering shots. Someone always asked, “Why did you take that one?” Someone else claimed, “This should be framed.” The bad photos weren’t deleted—they were kept, mocked, and loved anyway.

There was also risk. Entire rolls could be ruined. Overexposed. Underexposed. Accidentally opened. Sometimes the store lost them. Sometimes the machine malfunctioned. When things went wrong, the loss was permanent. No cloud backup. No second chance. That fragility made the good photos feel precious in a way digital images rarely do.

Photos didn’t live on screens. They lived in shoeboxes, albums with sticky pages, or plastic sleeves that stuck slightly to your fingers. You wrote dates and locations on the back in ballpoint pen, pressing carefully so the ink wouldn’t bleed through. Over time, the edges curled, the colors faded, and fingerprints appeared—evidence that these images had been handled, shared, and truly lived with.

Waiting for photos wasn’t just about patience—it was about trust. Trust in the process. Trust in memory. Trust that the moments you captured would come back to you transformed into something tangible. And when they finally did, they felt heavier than pixels ever could.

The wait made the reveal meaningful. It turned ordinary moments into something worth anticipating. In a world where you can now see everything instantly, something quiet and powerful was lost: the joy of wondering what your memories would look like when they finally returned to you.

Waiting for That Song on the Radio

In the 1980s, music didn’t follow you—you followed it.

If you loved a song, you couldn’t summon it on demand. You waited for it. You hoped. You listened. And sometimes, after hours or days of patience, the radio rewarded you.

The radio was a gatekeeper. DJs decided what played and when, and their voices became as familiar as old friends. You learned the rhythms of stations: which ones leaned pop, which played rock late at night, which saved the good stuff for the countdowns. You memorized time slots and show names because that’s where your chances lived.

Waiting for a song meant commitment. You kept the radio on in the background while doing homework, lying on the carpet, or staring out the window. Your attention drifted—but never too far. The moment you recognized the opening notes, everything stopped. Conversations were hushed. Fingers hovered over buttons. Hearts jumped.

If you were lucky enough to own a cassette deck with a record function, the ritual became even more intense. You sat inches from the radio, hand poised, trying to predict the exact second the DJ would stop talking. They always talked too much. Sometimes they talked over the intro on purpose. Sometimes they faded the song early. Every successful recording felt like a victory stolen from chaos.

And the imperfections were part of the magic. The DJ’s voice bleeding into the first few seconds. A bit of static. The click of the button at the end. These weren’t flaws—they were proof. Proof that you were there, listening, waiting, ready. That tape wasn’t a product; it was a souvenir of patience.

There was also disappointment. You waited all afternoon and the song never played. Or it came on while you were in the bathroom. Or the phone rang at the worst possible moment. You learned quickly that waiting didn’t guarantee reward—and somehow, that made the reward sweeter when it came.

Requesting a song added another layer of anticipation. You called the station, hoping to get through, hoping the DJ would pick up, hoping they’d actually play it. Then you waited again, unsure if your request had been forgotten or queued. When it finally played, there was a quiet thrill in knowing you had asked for this moment—and it had arrived.

Because songs were scarce, they mattered more. You didn’t get tired of them as quickly. Hearing a favorite track felt like running into someone you loved unexpectedly. You turned the volume up, sang louder, and let the moment fully land—because you didn’t know when it would happen again.

Waiting for that song on the radio taught patience, attention, and appreciation. It turned listening into an active act, not background noise. And when the music finally found you, it didn’t just sound good—it felt earned.

Waiting by the Phone

In the 1980s, the phone didn’t travel with you.

You traveled to the phone.

During that time, a ringing phone could change your entire day—but only if you were close enough to hear it. The phone was nailed to a wall, parked on a table, or squatting on a nightstand with a cord that never quite reached comfort. If you were waiting for a call, you arranged yourself around it like it was a small, unpredictable fire you had to tend.

You hovered. You lingered. You pretended to be busy within range.

The house took on a different sound when you were waiting. The TV volume crept lower. Footsteps softened. Every clatter from the kitchen made you wince, afraid it might drown out the ring. Time slowed into long, uneven stretches, broken only by your eyes flicking back to the phone again and again.

When the phone rang, it didn’t politely notify you—it exploded into the room. That bell cut through everything. Someone always shouted “Phone!” even though no one needed to be told. Chairs scraped. Someone lunged for it. Because if it rang too long, the moment was gone forever.

There was no voicemail for most of the decade. No caller ID. No proof that someone had even tried. If you missed the call, all you were left with was wondering. Did they call too early? Too late? Would they try again? Or was that it?

So you stayed close. You put off showers. You didn’t step outside “just for a second.” Leaving the house while waiting for a call felt reckless, like tempting fate. If you had to go, you announced it, left instructions, and trusted someone else to scribble a message on whatever paper was nearby and not lose it.

For teenagers, waiting by the phone was a special kind of torture. You sat on your bed, pretending not to care, pretending you weren’t counting rings in your head. Every time the phone rang, your heart jumped—hard—before your brain could catch up.

And most of the time, it wasn’t for you.

Wrong number. Aunt. Telemarketer. You tried to act normal as the receiver went back on the hook, but the disappointment lingered. The waiting reset itself instantly, heavier than before.

If someone else answered first, the suspense was unbearable. You froze, listening from the next room, decoding tone and pauses. Was your name coming? Or would the call end quietly, the chance slipping away without ceremony?

Busy signals had their own rhythm. You dialed. Rejected. Hung up. Tried again. Each attempt felt hopeful. Each buzzing tone felt personal. Connection wasn’t guaranteed—it had to be fought for.

When the call finally did happen, it mattered. You leaned against walls. You twisted the cord around your finger until it kinked. You lowered your voice when someone walked past. You talked longer than you needed to, because this moment had edges. When it ended, it ended completely.

And afterward, you just sat there.

The phone was silent again. The room felt emptier than before. You replayed every word, every laugh, every pause, wondering what it meant—and when the phone might ring again.

Waiting by the phone taught you how to live with uncertainty. It made connection feel rare and fragile. And when the call finally came, it didn’t just reach you—it justified every minute you spent listening for it.

Waiting for Letters in the Mail

In the 1980s, the mailbox was a portal to another world. It wasn’t just a metal box at the curb—it was a tiny theater of anticipation, a daily stage where hope, curiosity, and impatience performed together.

Waiting for letters meant more than waiting for news. It was a ritual. You would check the mailbox obsessively, sometimes multiple times a day, even when you knew there was nothing new. Each trip carried the same thrill and dread: a hand trembling slightly as you opened the lid, wondering if a letter had arrived, or if, once again, it would be empty.

There was a rhythm to it. Letters didn’t arrive on demand. They traveled by human hands, sorting machines, and trucks, often taking days—or even weeks—to reach you. And that delay made the words inside feel heavier, more significant. Birthdays, thank-you notes, love letters, postcards from vacations—each one had earned the journey, and every envelope felt like a little treasure chest.

The letter itself was a tactile experience. You held it between fingers, noting the texture of the paper, the color of the ink, the loops of handwriting that could reveal personality and mood. There were stamps to admire, postmarks to decipher, and sometimes even tiny smudges or wrinkles that reminded you this message had a life before it reached you. Opening a letter was deliberate. You slit the envelope, unfolded the paper, and read slowly, savoring every line, because once it was read, the moment was over—but the memory lingered.

And the waiting wasn’t solitary. Families and friends shared it. Children argued over who would check the mailbox first. Roommates or siblings peeked over each other’s shoulders to see what had arrived. For lovers writing back and forth, the anticipation could dominate days, filling afternoons with daydreams, notes scrawled in margins of schoolbooks, or staring out windows hoping the mail truck would arrive.

There were disappointments, too. Letters lost in transit, long delays, or weeks of silence could feel like punishment. Each empty mailbox was a tiny heartbreak—but that heartbreak made the eventual reward all the more thrilling. When a letter finally arrived, it wasn’t just paper with words. It was proof someone had thought of you, crossed distances and time just to reach you.

Waiting for letters in the mail taught patience in a uniquely intimate way. It slowed life down, forced attention, and made connections tangible. And when the envelope finally slid into your hand, when you finally unfolded that paper, the joy of anticipation was fully realized—it was a moment you remembered, long after the words had been read.

Waiting for the TV Schedule

In the 1980s, the television wasn’t a device you could command—it was a ritual you submitted to. You didn’t just “turn on Netflix” or “search YouTube.” You waited. And often, you waited for the TV schedule.

The TV guide was your oracle. Every week, a small booklet or newspaper section promised the shape of your evenings, listing shows in neat little boxes with times and channels. You circled your favorites with a pen or highlighter, planning entire nights around a single half-hour or hour. If the schedule wasn’t in your hands yet, you spent days in suspense, speculating which shows would air when, and sometimes which episodes would finally reveal the plot twist you’d been dying to see.

Even once you had the guide, waiting didn’t stop. You counted down the hours. After school, after work, after dinner—you positioned yourself in front of the TV early, tuned to the right channel, and sat there, ready. There was no instant replay. Miss a moment, and it was gone. Commercials weren’t interruptions—they were markers of time, part of the pacing of the evening, and a warning: the next scene was coming soon.

Families and friends participated in the ritual together. Everyone knew the schedule. Arguments erupted over priorities: who got to watch what, when, and on which set if the household had multiple TVs. Planning was strategic. You might record one show on a VCR while waiting for another to start, a delicate balance requiring careful attention and timing.

Speculation and gossip extended the waiting. You discussed plotlines in school hallways or office break rooms, trying to predict what would happen next, sharing tips about which shows were “can’t-miss” and which were “probably terrible.” Waiting became social as much as personal.

And the anticipation wasn’t just about entertainment—it was about timing your life to fit the schedule. A night out, a phone call, or a family dinner could be planned around when the show started. Life itself bent to the rhythm of the broadcast. Missing a program wasn’t just inconvenient—it was a small heartbreak.

Waiting for the TV schedule taught patience, foresight, and the pleasure of structured anticipation. When the hour finally came and the show began, it didn’t just play—it arrived. The build-up, the countdown, and the shared knowledge that everyone had been waiting for this moment made watching it feel electric. In the 1980s, the TV schedule wasn’t just a list of shows—it was the map of collective anticipation, a ritual that transformed ordinary evenings into events.

Waiting for the Movie Rental to Be Available

In the 1980s, movies were not on-demand. They didn’t stream, they didn’t download, and they certainly didn’t sit quietly in some digital library, ready whenever you felt like watching. If you wanted to see a popular film, it wasn’t enough to decide in the moment—you had to plan, anticipate, and, most importantly, wait.

Video rental stores were temples of cinematic desire. Rows of VHS tapes and Beta cassettes lined the shelves like treasure, their brightly colored cases promising adventure, romance, horror, or laughter. Each tape carried the echoes of previous renters: fingerprints on the plastic, scratches on the spine, the lingering smell of popcorn or soda from someone else’s living room. Popular films—The Empire Strikes Back, Back to the Future, Ghostbusters—were often nowhere to be found. One copy for a blockbuster could be checked out for weeks, leaving eager viewers to wander the aisles in frustration, imagining the story locked inside that lone tape.

The wait often began before you even left the house. You would call the store—if you were lucky enough to have a phone—and ask if the movie had returned yet. “Not yet,” they’d say, and you’d be forced to imagine the characters, the plot, and the final scenes, because there was no way to watch it until your name appeared on the list. When a rental was in high demand, stores kept physical waiting lists. You scribbled your name on a slip of paper, crossed your fingers, and hoped.

The anticipation transformed ordinary days into exercises in patience. You would rehearse conversations with friends who had already seen it, carefully extracting hints without getting spoiled. You might plot strategic visits to the store, hoping to catch the tape as soon as it was returned. You watched the streets, the clock, the calendar, all in silent calculation, waiting for that phone call or the lucky moment when a copy finally became available.

Waiting for a rental was also social. Everyone knew what was hot and what was not. You traded tips on which locations might have a hidden copy in the back. You discussed with classmates or coworkers the films you were desperate to see, building a shared narrative around anticipation. Sometimes, knowing someone else had already rented a copy made the wait even harder—you felt the absence of the story acutely, like a party you weren’t allowed to attend.

And then, when the day finally came, it was electric. Picking up the tape was a small triumph, a victory carved out of patience and persistence. You cradled the cassette in your hands, rushing home as though the story inside might escape if you dawdled. You examined the cover, inspected the spine, and carefully placed the tape into the VCR, savoring the ritual of pressing play. Every moment of that film felt heightened because you had waited for it. The tension, the joy, the laughter—it all arrived fully formed, amplified by the scarcity of access.

The limitations themselves made the experience richer. You couldn’t pause indefinitely, skip scenes, or binge-watch endlessly. Each viewing was a conscious act, a commitment. You rewound the tape carefully afterward, treating it like an artifact that had to be preserved, both for yourself and for the next renter who might be waiting just as anxiously as you had been.

In the end, waiting for a movie rental wasn’t just about watching a film—it was about inhabiting the suspense, imagining the story, and sharing that anticipation with others. It was a communal, almost sacred experience. The scarcity, the patience, the longing—all of it made the moment of finally watching feel electric. In a world before instant gratification, the wait itself was part of the magic, a prelude that made the experience of the movie unforgettable.

Waiting for Film to Load

In the 1980s, cameras weren’t just tools—they were mechanical companions, and every roll of film carried a little tension with it. Unlike today’s digital devices, where you can snap dozens of photos and see them instantly, film cameras required patience, precision, and an acceptance of the unknown.

Loading a roll of film was an art in itself. You opened the back of the camera, careful not to touch the shiny emulsion of the film. You aligned it with the sprockets, rolled it gently into place, and clicked the back closed. Then came the initial winding: a few turns of the advance lever until the first frame was ready. That small, mechanical motion created the first whisper of anticipation. Each click of the lever was a heartbeat of expectation, a signal that the camera was ready—but nothing had yet been captured.

The act of loading film slowed you down. It forced attention and intention. Unlike modern devices where you can spray photos endlessly, with film, each frame mattered. You measured each shot in your mind, imagined the exposure, the light, the angle, and the story you wanted to tell. Film didn’t forgive mistakes. Overexpose, underexpose, or misframe, and that moment was lost forever. The waiting during the loading phase gave each click of the shutter weight; each captured frame felt deliberate and precious.

And then there was the mental suspense. After loading, you knew every photograph would remain unseen until developed. You couldn’t peek, you couldn’t review. You held the future of the roll in your hands. Every vacation shot, every birthday party, every candid moment taken on that roll existed only as potential until the film was processed.

The anticipation extended to sharing as well. Family members might gather to see what had been captured once the roll returned from the lab. Until then, discussions about what might be on the film—funny faces, perfect shots, or total disasters—filled the days. The wait made the eventual reveal something of a small celebration, a ritual that transformed ordinary moments into treasured memories.

Waiting for film to load taught patience, mindfulness, and respect for the process. It made photography an experience, not just an outcome. That tension, that careful preparation, was part of the magic. Every roll of film began as a blank promise and, only after the wait, became proof that a moment had truly existed.

Waiting for the Arcade Game to Be Free

In the 1980s, the arcade was a kingdom of lights, sounds, and competition, and every machine was a coveted throne. But unlike home consoles, you couldn’t just grab a controller and start playing. The joystick and buttons were shared resources, and to play your favorite game—Pac-Man, Donkey Kong, Space Invaders—you often had to wait.

The waiting began the moment you spotted a full machine. Kids crowded around, quarters clutched in sweaty palms, eyes fixed on the screen. You paced, watched, and calculated. How many lives did the current player have left? Would they finish the level soon? Could you sneak a peek at the patterns, anticipate the next move, and be ready the instant the machine freed up? Every second of observation felt like preparation, a mental rehearsal of the game you hadn’t yet touched.

Arcade waiting was performative. You shifted weight from foot to foot, drummed your fingers, exchanged commentary with other hopeful players. Sometimes friendly, sometimes competitive, these moments created a unique social rhythm. You learned to negotiate space, to read body language, and to predict timing. And when a spot finally opened, it wasn’t just a chance—it was a small victory, a reward for patience and strategy.

The games themselves added urgency to the wait. High scores were public, displayed proudly at the top of the screen, a siren call to anyone watching. You didn’t just play to pass time—you played to etch your name into the collective memory of the arcade. Missing your turn could mean watching someone else claim the high score you’d been imagining for days, another layer of tension to the already long anticipation.

Even the act of feeding quarters into the machine had ceremony. Each coin made a satisfying clink as it slid into the slot, and you felt it register the promise of control, of participation, of agency in a tiny digital world. You gripped the joystick, feeling the plastic give under your fingers, and leaned in close to the screen, aware that this moment had been earned through patience.

The wait also heightened the drama of the experience. When you finally played, every ghost dodged, every barrel jumped, every alien shot carried weight. Your focus was absolute, your excitement sharp, and every success felt amplified by the prior tension. Losing a life hurt more—but winning felt electric.

Waiting for the arcade game to be free was about more than the game itself. It was about timing, strategy, community, and anticipation. It taught observation, patience, and the thrill of reward earned. And in a world where so much was immediate, the arcade reminded you that sometimes, the most exciting part of play was simply waiting for your turn.

Waiting for Summer, Birthdays, and Holidays

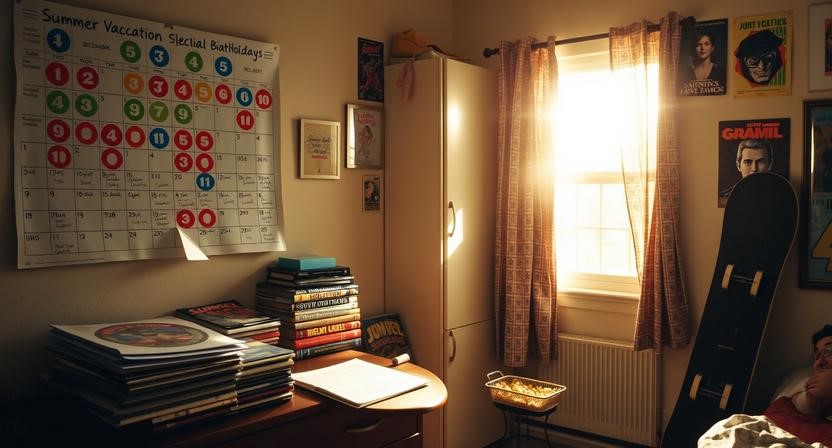

In the 1980s, waiting for special days was a season in itself. Summer, birthdays, and holidays didn’t just arrive—they loomed on the horizon, stretching out time with anticipation that made every ordinary day feel like part of the buildup.

Summer was never “here” until it was. You counted down the school days, each one dragging and racing at the same time. You imagined freedom: long afternoons on the street with bikes and skateboards, trips to the pool, video games and comic books scattered across the living room floor. Every sunset seemed to stretch longer, every Saturday a small rehearsal of the bliss that was coming. You measured time in heatwaves and daylight, feeling the tension between the present and the promise of unstructured days.

Birthdays carried their own slow burn of excitement. Weeks before, you watched for hints from friends and family, guessing gifts, planning celebrations, and rehearsing what you might say or do on your special day. Each passing day added layers to the anticipation. The decorations, the cake, the wrapping paper—they weren’t just the reward; they were part of the long buildup. You imagined faces lighting up, candles flickering, and the exact moment of unwrapping a gift. The waiting made the day feel sacred, a miniature event suspended in time.

Holidays amplified the same sense of prolonged expectation. Christmas, Halloween, Easter—they were months in the making. You marked calendars with circles and stars, planned costumes or wish lists, and watched the world slowly shift toward the celebration. Decorations creeping into stores, holiday specials on TV, and songs drifting over the radio all served as reminders: the moment was coming, but not yet. The waiting became a shared rhythm, experienced alongside siblings, friends, and neighbors, binding everyone to the same slow, collective countdown.

The beauty of these waits wasn’t just in the day itself—it was in the anticipation, the imagining, and the planning. You daydreamed endlessly, built stories in your mind, and let your imagination run wild. Ordinary moments became infused with magic because the extraordinary was still ahead.

Waiting for summer, birthdays, and holidays taught patience, imagination, and joy in the gradual unfolding of time. It transformed the calendar into a living thing, with suspense, excitement, and shared human experience written into every marked date. And when the day finally arrived, it wasn’t just a day—it was a culmination of weeks or months of hope, speculation, and longing. The wait made the experience unforgettable.

Waiting for Information

In the 1980s, information wasn’t at your fingertips. There were no smartphones pinging updates, no social media feeds scrolling endlessly, no instant access to search engines. If you wanted to know something—a sports score, the latest gossip, a phone number, the outcome of a school election—you had to wait. And waiting for information wasn’t just a delay; it was a tense, consuming, and surprisingly rich experience.

The anticipation started the moment a question formed in your mind. You might call a friend or family member, but there was no guarantee they’d pick up. You left messages on an answering machine, listening to that repetitive, mechanical beep over and over, hoping for a call back. You could write a letter or a note and drop it in the mailbox, but delivery took days. Every hour stretched, each one amplifying your curiosity. Even a small fact could feel monumental when access was delayed.

Gathering information was a social ritual. You asked friends at school, neighbors across the street, coworkers in the office. You traded tidbits in hallways or over lunch tables. The information didn’t arrive neatly; it often came distorted, exaggerated, or fragmentary, like a puzzle you had to assemble yourself. Waiting allowed your imagination to run wild. You predicted outcomes, rehearsed conversations, and built stories around incomplete facts. By the time the truth arrived, it carried a resonance that instant knowledge rarely delivers.

Mass media was another form of waiting. Sports scores arrived on TV or the radio, often delayed by hours. Newspapers were printed once a day, and deadlines meant that news could be outdated before you even saw it. Television broadcasts gave you a schedule to follow: the six o’clock news, the evening sports report, or a special segment on your favorite topic. You planned your day around these moments, timing your activities so you wouldn’t miss the critical update. Even weather forecasts were limited, and every bulletin felt like a precious glimpse into the future.

Waiting for information also had a tactile, ritualistic side. You might stand at the mailbox for the arrival of a letter with a long-awaited phone number or confirmation. You might dial the number repeatedly, counting each ring, hoping to catch someone home. You might huddle around a small transistor radio, twisting the dial, scanning channels, straining to hear a report over static. Every act was deliberate, conscious, and imbued with suspense.

Emotionally, the wait could be exhilarating or agonizing. Every delay built tension. You imagined all possible outcomes: the good, the bad, the funny, or the disappointing. You speculated wildly with friends: “Maybe they’ll call today!” or “What if we got the wrong results?” The longer the wait, the more the eventual revelation mattered. The arrival of information was a small event in itself—sometimes celebrated with friends, sometimes with private relief, sometimes accompanied by laughter, groans, or disbelief.

Waiting for information in the 1980s was also a shared human experience. Entire communities, classrooms, or workplaces would wait together for the same update. Whether it was a contest result, a school announcement, or the latest chart-topping song to be reported in the newspaper, anticipation created connection. It bound people into a collective rhythm of curiosity and suspense. Conversations were dominated by speculation, debates, and whispered predictions. The waiting itself became part of the story, as much as the information finally received.

This type of waiting taught patience and endurance in a way modern life rarely does. It trained attention, sharpened memory, and demanded mindfulness. When the awaited answer finally arrived, it was richer, more satisfying, and more memorable than anything received instantly could be. The facts themselves were important—but the journey of waiting, imagining, and speculating was just as vital.

In a world where everything is now immediate, the 1980s’ slow pace of information feels almost foreign. But there was a beauty in that slowness. Waiting for information wasn’t frustrating—it was immersive. It was a practice of hope, imagination, and shared suspense. And when the answer finally came, it didn’t just inform—it rewarded.

Waiting as a Shared Experience

In the 1980s, waiting wasn’t just a solitary act—it was something you did together. Whether it was anticipating the next episode of your favorite TV show, the arrival of a letter, a phone call, or even the chance to play an arcade game, waiting often became a communal rhythm, tying people together in shared suspense and excitement.

School hallways, living rooms, and neighborhood streets were filled with hushed speculation and whispered predictions. Kids compared notes about which video game machine might be free first, or which movie tape might finally be available at the rental store. Friends traded information about radio requests, sports scores, or gossip, each conversation an exercise in collective anticipation. Even if you were waiting alone in your bedroom, your mind was never truly solitary—you were part of a network of people, all caught in the same forward-moving tension, all invested in the unknown.

Families also participated in this collective waiting. Dinner time could double as a strategic planning session: who would check the mailbox first? Who would call the rental store? When would the TV guide arrive, and who got to circle the must-see shows? The waiting gave ordinary moments purpose. It created small rituals: pacing the living room, rehearsing lines from a film or a song you hoped to record, comparing your high score with a sibling while waiting for your turn on the arcade machine. Every pause became a shared heartbeat, every delayed event a chance to bond.

Public spaces also amplified shared anticipation. At the arcade, you weren’t just waiting for a machine—you were part of a crowd, collectively holding your breath until someone lost a life or stepped aside. At the record store, fans lingered by the new release shelf, hoping the hottest album had arrived early. At the mailbox, neighbors might chat about their own letters or packages, trading jokes and stories while waiting together. Waiting was social, interactive, and often competitive, transforming simple patience into communal theater.

Even media itself reinforced shared waiting. A TV show started at 8:00 PM, whether you were ready or not. Miss it, and the conversation the next day would leave you out. A song might play on the radio only once or twice a day, creating a collective longing for those who shared the frequency. You weren’t just hoping to hear it—you were hoping everyone else would have the same chance to be caught up in the thrill, and then you could talk about it, compare recordings, and replay the excitement.

Waiting together also intensified the emotional stakes. Shared suspense created empathy. When a friend finally got a call you’d both been anticipating, you felt their relief as keenly as your own. When a tape became available, everyone who had been hoping for it felt the victory collectively, cheering silently or aloud. The tension of waiting, stretched out over hours or days, became a connective tissue between people.

In a world where instant access is now the norm, the 1980s’ shared waiting feels almost magical. It wasn’t just about patience—it was about connection. Waiting turned simple desires into communal experiences, transforming anticipation into shared storytelling, collective suspense, and emotional resonance. To wait together was to participate in something bigger than yourself: a slow, deliberate rhythm that bound friends, families, and communities in the invisible, thrilling threads of anticipation.

What We Lost When Waiting Disappeared

The magic of the 1980s wasn’t just in the neon colors, the music, or the movies—it was in the waiting. Every delayed phone call, every film roll, every letter in the mailbox created a kind of suspense that modern life has almost entirely erased. Today, everything is immediate. Press a button, and it’s yours: a message, a song, a movie, an answer. Instant access has convenience—but it has also taken something deeper away.

When waiting disappeared, so did the build-up. Anticipation gave moments weight. You didn’t just watch a movie—you imagined it for days, replaying scenes in your mind, discussing it with friends, and wondering if it would live up to your expectations. You didn’t just hear a song—you listened for it on the radio, memorizing every lyric as if the wait made it richer. Waiting allowed imagination to participate in the experience, making the eventual reward feel earned, meaningful, and almost miraculous.

We also lost patience as a learned skill. The 1980s taught you how to tolerate delays, how to plan, and how to savor the slow unfolding of life. You timed errands around the TV schedule, you rehearsed lines of a song before you could record it, you practiced restraint while counting down days to a birthday or a summer vacation. Modern instant access encourages immediacy and impulse; the slow anticipation that once added emotional depth is gone.

Shared experiences suffered, too. Waiting often connected people—neighbors chatting while checking the mailbox, siblings debating who would get the arcade machine first, friends gathering to discuss the latest film release. Anticipation was social. Today, when everything is instantly available, the communal thrill of waiting has been replaced by isolated consumption. Everyone can get it at once—but no one truly has to wait together.

And perhaps most poignantly, we lost mystery and surprise. The unknown is exhilarating. In the 1980s, you didn’t know exactly what a letter said, how a photo had turned out, or whether a game you wanted would be free. That uncertainty created a subtle tension, a private thrill that sharpened attention and made every reveal vivid. Instant access removes that suspense; everything is predictable, and everything is immediate. The excitement of “what if?” has been replaced with the boredom of “already here.”

In short, when waiting disappeared, we gained speed and convenience—but we lost depth. We lost the small, quiet joys of delayed gratification. We lost the art of savoring a moment before it arrived. We lost shared anticipation that turned ordinary experiences into social and emotional rituals. Life is faster now, but the 1980s remind us that sometimes the pace of waiting was as meaningful as the reward itself.

Why Waiting Felt Better Than Instant Access

There’s a quiet truth about the 1980s: waiting wasn’t just an inconvenience—it was part of the pleasure. Each delayed moment, whether it was a phone call, a song on the radio, a movie rental, or a letter in the mail, gave life texture. Waiting created tension, excitement, and imagination. It made rewards matter. In a world of instant access, we rarely feel that kind of satisfaction anymore.

Waiting made experiences deliberate. You didn’t passively consume life—you approached it with intention. You prepared for it, anticipated it, and imagined it long before it arrived. You thought about how you would react, what it might feel like, who would be there, and what you might say or do. The wait transformed ordinary events into mini-rituals, giving them weight and significance that instant access can’t replicate.

It also made the experience communal. Waiting connected people in ways we seldom feel today. Families counted down to TV shows together. Friends compared notes on who had recorded a favorite song. Gamers strategized together while eyeing the arcade machine. The anticipation was shared, creating bonds, inside jokes, and stories that would linger far longer than the thing you were waiting for. Instant access may give everyone the outcome at the same time, but it rarely builds community in the process.

And waiting sharpened the imagination. When you didn’t know exactly what a photo would look like, what a song would sound like, or what a letter contained, your mind filled in the blanks. You rehearsed scenes, visualized outcomes, and let anticipation build suspense. The eventual reveal carried emotional weight because you had invested in it mentally and emotionally. Immediate access skips that investment; the magic is gone before it even begins.

There’s also a satisfaction that comes from patience itself. Waiting teaches restraint and appreciation. It shows you that some things are worth time, that some moments deserve to be savored. When the reward finally arrives after days, hours, or even weeks of anticipation, it feels earned, celebrated, and unforgettable. That slow march toward fulfillment made ordinary experiences extraordinary.

In the end, waiting felt better than instant access because it gave life a rhythm, a suspense, and a shared heartbeat. It made joy more intense, connections more meaningful, and experiences more vivid. The 1980s were not just a decade of pop culture—they were a decade of anticipation, of suspense, and of cherishing the slow unfolding of life itself.

The waiting wasn’t a flaw of the era—it was its magic. And in that magic, every ring of the phone, every returned film, every arcade victory, and every letter in the mailbox became more than just a moment—they became an experience.

Leave a comment